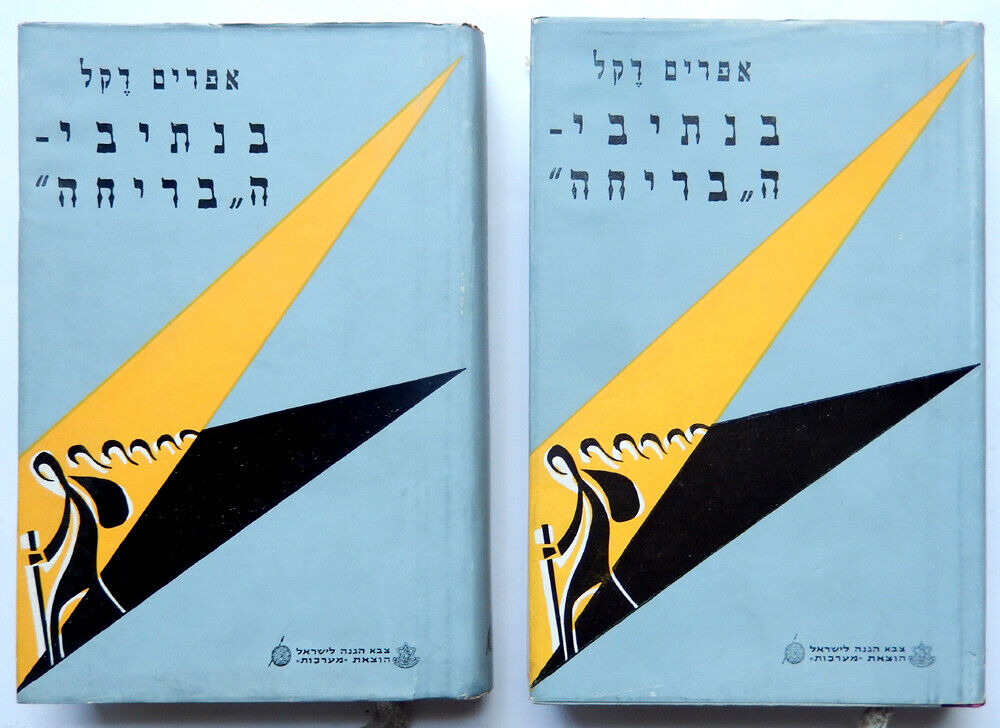

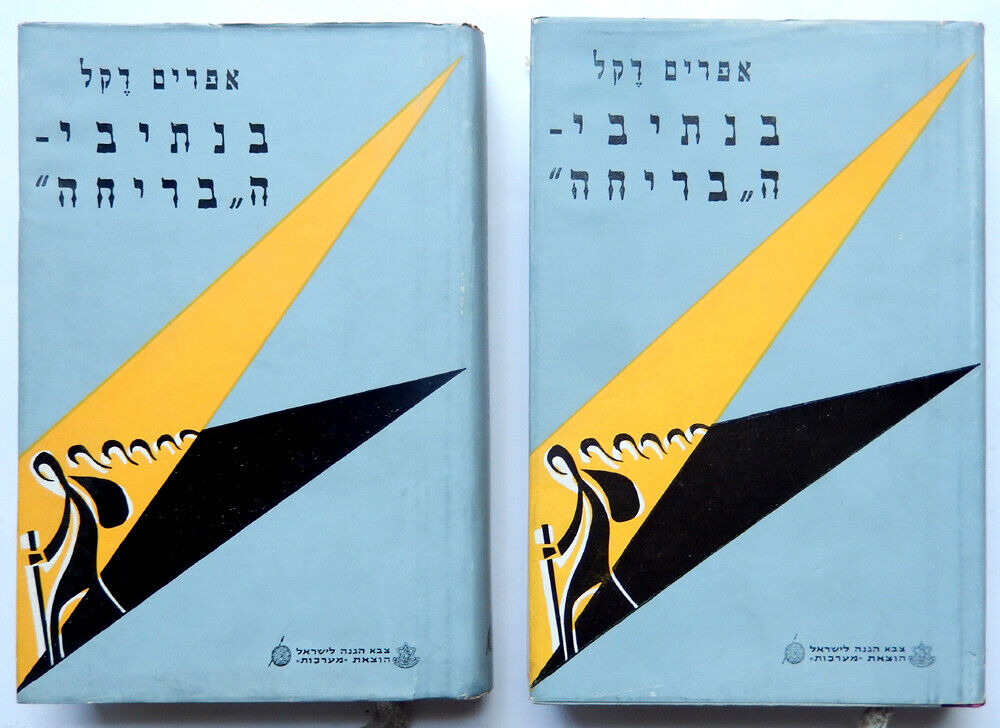

1959 HABRICHA THE ESCAPE SHEERIT HAPLETA JEWISH BOOK 2 VOLS DP CAMPS HOLOCAUST For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1959 HABRICHA THE ESCAPE SHEERIT HAPLETA JEWISH BOOK 2 VOLS DP CAMPS HOLOCAUST :

$75.00

HABRICHA THE ESCAPE SHEERIT HAPLETA BOOK 2 VOLS DP CAMPS HOLOCAUST

Benetevi HaBricha-Flight to the Homeland. Written by Ephraim Dekel, published by \"Maarachot\" Israel defence Force publishing house. Printed by Military press 665 in Israel in 1959. Two volumes with photos Extensive material on the DP camps and rescue work following the Holocaust and boats to Palestine.Ephraim Dekel washigh-ranking member of the Haganah and one of the organizers of the “Escape orgamization\". Excellent near MINT condition. Hardcover with dust jacket. Size: 9x6 inch. 572 pages.Winning buyer pays $15.00 Postage international registered air mail.

Authenticity 100% Guaranteed

Please have a look at my other listings.Good movement operated in Europe from the end of World War II until the establishment of the State of Israel, and was responsible for the smuggling of some three hundred thousand Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe to the southwest - to the ports of the Mediterranean, survivors who chose to abandon the killing valley of Europe in order to establish a home for themselves in the Land of Israel.The roots of the \"Bricha\" were a spontaneous organization of Holocaust survivors who came out of camps, forests, and hiding places and began organizing for mutual assistance. They were orphans, bereaved, last descendant of their families. The first to organize were Jewish partisans and graduates of the Zionist youth movements. They were organized in \"kibbutzim\" - where the refugees got a blanket, a pair of pants, food and shelter - a kind of family and first address. The survivors then met with the soldiers of the Jewish Brigade of the British Army, who exploited their status and the means at their disposal for the benefit of their fellow survivors. Many of the soldiers remained in Europe after being released from the \"Brigade\" in order to continue their activities.Later on, the \"Mosad for Aliyah Bet\" of the Haganah, which was established to help Jews immigrate to Palestine despite the ban imposed by the British Mandate authorities, undertook the management of the escape. The Palestine emissaries of the Mossad set up a network of lanes and transit camps across Europe. With their assistance and leadership, the Bricha movement became one of the most important elements in the immigration to Palestine and in the struggle for the establishment of the State of Israel.In Poland after the war there was political unrest and the Jews who remained there or returned to it suffered from alienation and anti-Semitism. In 1946, Polish rioters in the town of Kielce staged a pogrom against Jewish survivors. This massacre has become a turning point. There was no longer any need to urge the persecuted Jews to leave Poland. The ongoing anti-Semitism and the longing for a warm and secure home in their own homeland forced tens of thousands to join the Zionist organizations.A mass influx of Jews from Poland through Romania, Czechoslovakia, Ukraine and Hungary to the DP camps in Germany, Austria and Italy, controlled by the Allies began. From there they continued to the ports of Italy and southern France en route to Eretz Israel.The \"Irgun Ha - Bricha\" dealt with the logistics involved in this movement: transportation from city to city and from country to country, crossing border crossings with bribes and forged documents in the organization \'s labs, crossing borders on foot and snow, organizing transit camps and taking care of those on their way to seaports.Among the immigrants were thousands of orphaned Jewish children who were rounded up, rescued or rescued by the \"Irgun Ha - Bricha\" from convents, Christian families, caves and hideouts throughout Europe. These children needed care, care, education, and love that had been denied them during the war years.On their way to Eretz Israel, some of the survivors lived in DP camps in the territories held by the Allies in Germany, Austria, and Italy. In these camps the Bericha conducted extensive support and rehabilitation activities with the assistance of American Jewish organizations, especially the Joint, whose contribution was invaluable.Members of the Yishuv in Palestine who served in the \"Jewish Brigade\" and in the Transport Battalion, and were active in the struggle against the Nazis within the framework of the British army, contributed greatly to the Bricha. They provided military vehicles for the transportation of the refugees, assisted in the treatment of the camp residents, and carried out vocational training programs for their rehabilitation. At the end of the war, many of the soldiers chose to remain in Europe for a long time and continue their contribution to the national mission.As time went by it became clear that the Bericha had gone beyond its original form, and together with the Haapala movement played an important political role in the struggle of the Jewish people for its independence. The tens of thousands of Holocaust survivors who moved in Europe without a home and without a future created an international problem that, in practice and morally, undermined the British \"White Paper\" policy, which limited the entry of Jews to the Land of Israel. The Anglo-American Committee (1946) and the UNSCOP Committee (1947) were established in order to solve the problem, and members of the committees visited the displaced persons camps in Germany and recommended that survivors of the Holocaust immigrate to Eretz Israel. The decision of the UN General Assembly on November 29, 1947, to establish a Jewish state in Palestine.The Bericha movement on the roads of the European continent and the Haapala movement on the routes of the Mediterranean Sea, both under the umbrella of the Mossad Le\'Aliyah Bet, headed by Shaul Avigur, are the two parts that comprise the story of the rise of She\'erith Hapleitah to Israel and constitute a glorious chapter in the history of modern Jewish history . It is a chapter of heroism, courage, initiative and trickery that was characterized by sacrifice and love of the people and the homeland, a chapter that took place between two dramatic events of hysteria, namely, the Holocaust and the establishment of the State of Israel.Bricha (Hebrew: בריחה, translit. Briẖa, \"escape\" or \"flight\"), also called the Bericha Movement,[1] was the underground organized effort that helped Jewish Holocaust survivors escape post–World War II Europe to the British Mandate for Palestine in violation of the White Paper of 1939. It ended when Israel declared independence and annulled the White Paper.July 15, 1945. Buchenwald survivors arrive in Haifa to be arrested by the British.After American, British and Soviet armed forces liberated the camps, survivors suffered from disease, severe malnutrition and depression. Many were displaced persons who were unable to return to their homes from before the war. In some areas the survivors continued to face antisemitic violence; during the 1946 Kielce pogrom in Poland 42 survivors were killed when their communal home was attacked by a mob. For many of the survivors, Europe had become \"a vast cemetery of the Jewish people\" and \"they wanted to start life over and build a new national Jewish homeland in Eretz Yisrael.\"[1][2]The movement of Jewish refugees from the Displaced Persons camp in which they were held (one million persons classified as \"not repatriable\" remained in Germany and Austria) to Palestine was illegal on both sides, as Jews were not officially allowed to leave the countries of Central and Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union and its allies, nor were they permitted to settle in Palestine by the British.In late 1944 and early 1945, Jewish members of the Polish resistance met up with Warsaw ghetto fighters in Lubin to form Bricha as a way of escaping the antisemitism of Europe, where they were convinced that another Holocaust would occur. After the liberation of Rivne, Eliezer and Abraham Lidovsky, and Pasha (Isaac) Rajchmann, concluded that there was no future for Jews in Poland. They formed an artisan guild to cover their covert activities, and they sent a group to Cernăuţi, Romania to seek out escape routes. It was only after Abba Kovner, and his group from Vilna joined, along with Icchak Cukierman, who had headed the Jewish Combat Organization of the Polish uprising of August 1944, in January 1945, that the organization took shape. They soon joined up with a similar effort led by the Jewish Brigade and eventually the Haganah (the Jewish clandestine army in Palestine).Officers of the Jewish Brigade of the British army assumed control of the operation, along with operatives from the Haganah who hoped to smuggle as many displaced persons as possible into Palestine through Italy. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee funded the operation.Almost immediately, the explicitly Zionist Berihah became the main conduit for Jews coming to Palestine, especially from the displaced person camps, and it initially had to turn people away due to too much demand.After the Kielce pogrom of 1946, the flight of Jews accelerated, with 100,000 Jews leaving Eastern Europe in three months. Operating in Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia through 1948, Berihah transferred approximately 250,000 survivors into Austria, Germany, and Italy through elaborate smuggling networks. Using ships supplied at great cost[citation needed] by the Mossad Le\'aliyah Bet, then the immigration arm of the Yishuv, these refugees were then smuggled through the British cordon around Palestine. Bricha was part of the larger operation known as Aliyah Bet, and ended with the establishment of Israel, after which immigration to the Jewish state was legal, although emigration was still sometimes prohibited, as happened in both the Eastern Bloc and Arab countries, see, for example refusenik.The Jewish Infantry Brigade Group,[2] more commonly known as the Jewish Brigade Group[3] or Jewish Brigade,[4] was a military formation of the British Army in World War II. It was formed in late 1944[2][3] and was recruited among Yishuv Jews from Mandatory Palestine and commanded by Anglo-Jewish officers. It served in the latter stages of the Italian Campaign, and was disbanded in 1946.After the war, some members of the Brigade assisted Holocaust survivors to emigrate to Mandatory Palestine as part of Aliyah Bet, in defiance of British restrictions.[5][6]Contents1 Background1.1 Anglo-Zionist relations1.2 Origins of the Jewish Brigade2 Jewish Brigade2.1 Creation2.2 Military engagements3 Post-war deployment and disbandment3.1 Involvement in the Bricha3.2 Military legacy4 Legacy4.1 Medals and awards4.2 Legacy4.3 In popular culture5 Partial list of notable veterans of the Jewish Brigade6 See also7 References8 Sources9 External linksBackgroundAnglo-Zionist relationsJewish Brigade headquarters under both Union Flag and Zionist flagAfter World War I, the British and the French empires replaced the Ottoman Empire as the preeminent powers in the Middle East. This change brought closer the Zionist Movement\'s goal of creating a Jewish state. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 indicated that the British Government supported the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine in principle, marking the first official support for Zionist aims. It led to a surge of Jewish emigration in 1918–1921, known as the \"Third Aliyah\".[7] The League of Nations incorporated the Declaration in the British Mandate for Palestine in 1922. Jewish immigration continued through the 1920s and 1930s, and the Jewish population expanded by over 400,000 before the beginning of World War II.[7]Brigadier Ernest Benjamin, commander of the Jewish Brigade, inspects the 2nd Battalion in Palestine, October 1944.In 1939, however, the British Government of Neville Chamberlain appeared to reject the Balfour Declaration in the White Paper of 1939, abandoning the idea of establishing a Jewish Dominion. When the United Kingdom declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, stated: \"We will fight the White Paper as if there is no war, and fight the war as if there is no White Paper.\"[8]Origins of the Jewish BrigadeChaim Weizmann, the President of the Zionist Organization (ZO), offered the British government full cooperation of the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine. Weizmann sought to establish an identifiably Jewish fighting formation within the British Army. His request for a separate formation was rejected, but the British authorized the enlistment of Palestinian volunteers in the Royal Army Service Corps and in the Pioneer Corps, on condition that an equal number of Jews and Arabs was to be accepted. The Jewish Agency promptly scoured the local Labour Exchange offices to recruit enough Arab unemployed as \"volunteers\" to match the number of Jewish volunteers, and others were recruited from the lower strata of the Arab population offering cash bounties for enlistment. The quality of the recruits was, not surprisingly, abysmally low, with a very high desertion rate particularly among the Arab component, so that at the end most units ended up formed largely by Jews. The volunteers were formed in a RASC muleteers unit and a RASC Port Operating Company, and in the Pioneers Companies 601 to 609 (all but two lost during the Greece Campaign, with the last two returned to Palestine and disbanded there). From 1942, a large number of further Palestinian Arab/Jew mixed units were formed, still with the same mixed ethnic composition and the same quality problems encountered in the Pioneers Companies, including six RASC (Jewish) Transport Units,[9] a women\'s Auxiliary Territorial Service and a Woman Territorial Air Force Service[10] and several auxiliaries in local units of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Royal Engineers and Royal Army Medical Corps. Nine non-combat infantry companies were also raised as part of the Royal East Kent Regiment (\"the Buffs\"), to be used as guards for prisoners-of-war camps in Egypt. On August 1942 the Palestine Regiment was formed, again plagued by the same mixed recruiting and its associated low quality problems (the regiment was derisively called the \"Five Piastre Regiments\", due to the large number of Arab \"volunteers\" that had enlisted just for the cash bonus provided by the Jewish Agency).[11]However, there was no designated all-Jewish, combat-worthy formation. Jewish groups petitioned the British government to create such a force, but the British refused.[12] At that time, the White Paper was in effect, limiting Jewish immigration and land purchases.[6]Some British officials opposed creating a Jewish fighting force, fearing that it could become the basis for Jewish rebellion against British rule.[6] In August 1944, Winston Churchill finally agreed to the formation of a \"Jewish Brigade\". According to Rafael Medoff, Churchill consented because he was \"moved by the slaughter of Hungarian Jewry [and] was hoping to impress American public opinion.\"[12]Jewish BrigadeCreation1st Battalion of the Jewish Brigade on paradeAfter early reports of the Nazi atrocities of the Holocaust were made public by the Allied powers in the spring and early summer of 1942,[13] British Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent a personal telegram to the US President Franklin D. Roosevelt suggesting that \"the Jews... of all races have the right to strike at the Germans as a recognizable body.\" The president replied five days later saying: \"I perceive no objection...\"After much hesitation, on July 3, 1944, the British government consented to the establishment of a Jewish Brigade with hand-picked Jewish and also non-Jewish senior officers. On 20 September 1944 an official communique by the War Office announced the formation of the Jewish Brigade Group of the British Army and the Jewish Brigade Group headquarters was established in Egypt at the end of September 1944 (the formation was styled a brigade group because of the inclusion under command of an artillery regiment). The Zionist flag was officially approved as its standard. It included more than 5,000 Jewish volunteers from Mandatory Palestine organized into three infantry battalions of the Palestine Regiment and several supporting units.1st Battalion, Palestine Regiment2nd Battalion, Palestine Regiment3rd Battalion, Palestine Regiment200th Field Regiment (Royal Artillery)A march in Tel Aviv for the British army recruiting during World War IIThe New York Times dismissed it as a \"token\"[citation needed] while The Manchester Guardian lamented, \"The announcement that a Jewish Brigade will fight with the British Army is welcome, if five years late. One regrets that the British Government has been so slow to seize a great opportunity.\"[14]Military engagementsMen of the Jewish Brigade ride on a Churchill tank in North Italy, 14 March 1945Jewish Brigade soldiers in TarvisioJewish Brigade troops on the Italian-Austrian borderIn October 1944, under the leadership of Brigadier Ernest F. Benjamin, the brigade group was shipped to Italy and joined the British Eighth Army in November, which was engaged in the Italian Campaign under the 15th Army Group.[6][15]Joseph Wald, a Jewish Brigade soldier, carries an artillery shell. The Hebrew inscription on the shell translates as \"A gift to Hitler.\"The Jewish Brigade took part in the Spring Offensive of 1945. It took positions on the front line for the first time on March 3, 1945 along the south bank of the Senio River, and immediately began engaging in small-scale actions against German forces, facing the 42nd Jäger Division and the 362nd Infantry Division. The brigade carried out aggressive patrolling during which it engaged in numerous firefights in order to improve its positions, clear the south bank of German troops, and take prisoners, and carried out small-scale raids against German positions across the river to test the enemy\'s strength and map out enemy defensive positions. In one notable raid, it was supported by tanks of the North Irish Horse and South African Air Force fighter aircraft. The South African pilots, many of whom were Jewish, flew in a Star of David formation during their attack run as a tribute to the brigade. During the raid, the brigade\'s infantrymen ran ahead of the tanks and mopped up the German positions, returning with prisoners and greatly impressing the seasoned troops of the North Irish Horse.[16] The brigade first entered into major combat operations on March 19–20, 1945 at Alfonsine.[17] In its first sustained action on March 19, the brigade killed 19 German soldiers and took 11 prisoner for the loss of 2 dead and 3 wounded in a series of clashes. The brigade then moved to the Senio River sector, where on March 27 it fought against elements of the German 4th Parachute Division commanded by Generalleutnant Heinrich Trettner.[18] From April 1-9, the brigade again engaged the Germans in a series of small-scale clashes. It returned to offensive operations during the \"Three Rivers Battle\", crossing the Senio River on April 10 and capturing the two positions allocated to it, establishing a bridgehead and widening it the following day. It was assigned to clear out a German redoubt to the left of its position that another Allied unit had failed to capture. The brigade managed to complete the mission in a fierce battle, wiping out all enemy positions in fifteen minutes.[19][17][20] It subsequently engaged in a series of small-scale clashes and captured Monte Ghebbio in a battle with German paratroopers. The brigade was then removed from the frontline for rest and refit before the liberation of Bologna (April 21, 1945).[17] The brigade\'s engineering units also assisted in bridging the Po River to enable Allied forces to cross it. The Jewish Brigade spent 48 days on the frontline in Italy - March 3 to April 20, 1945.[21]The commander of the British 10th Corps praised the Jewish Brigade\'s performance:The Jewish Brigade fought well and its men were eager to make contact with the enemy by any means available to them. Their staff work, their commands and their assessments were good. If they get enough help they certainly deserve to be part of any field force whatsoever.[22]There are indications that brigade members summarily executed surrendering German soldiers, particularly SS soldiers, in order to take revenge for the Holocaust. Although Brigadier Benjamin urged his troops not to kill surrendering Germans, emphasizing that intelligence gleaned from interrogation of prisoners would hasten the end of the war, he and his staff understood the desire for vengeance among the soldiers, and no Jewish Brigade soldier was ever punished for killing or otherwise mistreating surrendering enemy troops.[23]The Jewish Brigade was represented among the liberating Allied units at a papal audience. The Jewish Brigade was then stationed in Tarvisio, near the border triangle of Italy, Yugoslavia, and Austria. They searched for Holocaust survivors, provided survivors with aid, and assisted in their immigration to Palestine.[6] They played a key role in the Berihah\'s efforts to help Jews escape Europe for British Mandatory Palestine, a role many of its members were to continue after the Brigade disbanded. Among its projects was the education and care of the Selvino children. In July 1945, the Brigade moved[15] to Belgium and the Netherlands.Overall, in the course of World War II, the Jewish Brigade\'s casualties were 83 killed in action or died of wounds and 200 wounded.[24] Its dead are buried in the Commonwealth\'s Ravenna War Cemetery at Piangipane.[25]Post-war deployment and disbandmentMain article: Tilhas Tizig GesheftenTilhas Tizig Gesheften (commonly known by its initials TTG, loosely translated as \"kiss [literally, lick] my arse business\") was the name of a group of Jewish Brigade members formed immediately following the Second World War. Under the guise of British military activity, this group engaged in the assassination of Nazis, facilitated the illegal immigration of Holocaust survivors to Mandatory Palestine, and smuggled weaponry to the Haganah.[6]The Jewish Brigade also joined groups of Holocaust survivors in forming assassination squads known as the Nakam for the purpose of tracking down and killing former SS and Wehrmacht officers who had participated in atrocities against European Jews. Information regarding the whereabouts of these fugitives was gathered either by torturing imprisoned Nazis or by way of military connections. The British uniforms, military documentation, equipment, and vehicles used by Jewish Brigade veterans greatly contributed to the success of the Nokmim. The number of Nazis the Nokmim killed is unknown, but may have been as high as 1,500.[26][27][28]After assignment to the VIII Corps District of the British Army of the Rhine (Schleswig-Holstein), the Jewish Brigade was disbanded in the summer of 1946.[29]Involvement in the BrichaMany members of the Jewish Brigade assisted and encouraged the implementation of the Bricha. In the vital, chaotic months immediately before and after the German surrender, members of the Jewish Brigade supplied British Army uniforms and documents to Jewish civilians who were facilitating the illegal immigration of Holocaust survivors to Mandatory Palestine. The most notable example was Yehuda Arazi, code name \"Alon,\" who had been wanted for two years by the British authorities in Palestine for stealing rifles from the British police and giving them to the Haganah. In 1945, Arazi and his partner Yitzhak Levy travelled from Mandatory Palestine to Egypt by train, dressed as sergeants from the Royal Engineers. From Egypt, the pair travelled through North Africa to Italy and, using false names, joined the Jewish Brigade, where Arazi secretly became responsible for organising illegal immigration. This included purchasing boats, establishing hachsharot, supplying food, and compiling lists of survivors.[30]When Arazi reached the Jewish Brigade in Tarvisio in June 1945, he informed some of the Haganah members serving in the Brigade that other units had made contact with Jewish survivors. Arazi impressed upon the Brigade their importance in Europe and urged the soldiers to find 5,000 Jewish survivors to bring to Mandatory Palestine.[31] Jewish Brigade officer Aharon Hoter-Yishai recalled that he doubted the existence of 5,000 Jewish survivors; regardless, the Jewish Brigade accepted Arazi\'s challenge without question. For many Jewish soldiers, this new mission justified their previous service in the British forces that had preceded the creation of the Jewish Brigade.[32]1948 Art Celabrating the Birth of Israel showing a soldier of the Jewish Brigade at lower left by Arthur SzykAnother Jewish Brigade soldier actively involved in the Bricha was Israel Carmi, who was discharged from the Jewish Brigade in the autumn of 1945. After a few months, the Secretariat of Kibbutz HaMeuchad approached Carmi about returning to Europe to assist with the Bricha. Carmi\'s previous experience working with survivors made him an important asset for the Bricha movement. He returned to Italy in 1946 and attended the 22nd Zionist Congress in Basel, where he gained insight into how the Berihah operated throughout Europe. Carmi proposed establishing a second Berihah route across Europe in the event that the existing route collapsed. In addition, he also proposed dividing the Bricha leadership into parts: Mordechai Surkis, working from Paris, would be responsible for the financial workings; Ephraim Dekel in Prague would run the administrative element, and oversee the Berihah in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Germany; and Carmi, working from Prague, would oversee activities in Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Romania.[33]The Fighters against Nazis MedalJewish Brigade soldiers, assisting with the Bricha, specifically took advantage of the chaotic situation in post-war Europe to move Holocaust survivors between countries and across borders. Soldiers were intentionally placed by Merkaz Lagolah at transfer points and border crossings to assist the Jewish DPs (displaced persons).[34] For example, Judenberg, a sub-camp of the Mauthausen concentration camp, acted as a Berihah point where Brigade soldiers and partisans worked together to assist DPs. Similarly, in the city of Graz, a Bricha point was centred in a hotel where a legendary Bricha figure, Pinchas Zeitag, also known as Pini the Red or \"Gingi,\" organised transports westwards to Italy.[35] One of the Jewish Brigade\'s greatest contributions to the Bricha was the use of their British Army vehicles to transport survivors (up to a thousand people at a time) in truck convoys to Pontebba, the brigade\'s motor depot. These secret transports generally arrived at 2 or 3 a.m., and the Brigade always ensured that DPs were greeted by a soldier or an officer and welcomed into a dining hall with food and tea. Everyone was given a medical examination, a place to sleep, and clean clothing; and within a few days the group was moved to hachsharot in Bari, Bologna and Modena. After recuperating and completing their hachshara training, the DPs were taken to ports where boats would illegally set sail for Mandatory Palestine.[36] Historians estimate that the Jewish Brigade assisted in the transfer, between 1945 and 1948, of 15,000–22,000 Jewish DPs as part of the Bricha and the illegal immigration movemeh\'erit ha-Pletah is the name of an organization formed by Jewish Holocaust survivors living in Displaced Persons (DP) camps, assigned with acting on their behalf with the Allied authorities. The organization was active between 27 May 1945 and 1950-51, when it dissolved itself.[1][2]Sh\'erit ha-Pletah (שארית הפליטה) is Hebrew for surviving remnant, and is a term from the Book of Ezra and 1 Chronicles (Ezra 9:14; 1 Chr 4:43).[citation needed]A total of more than 250,000 Jewish survivors spent several years following their liberation in DP camps or communities in Germany, Austria, and Italy, since they could not, or would not, be repatriated to their countries of origin. The refugees became socially and politically organized, advocating at first for their political and human rights in the camps, and then for the right to emigrate to the countries of their choice, preferably British-ruled Mandatory Palestine, the USA and Canada. By 1950, the largest part of them did end up living in those countries; meanwhile British Palestine had become the Jewish State of Israel.[citation needed]Contents1 Formation of the DP camps2 Harrison report3 Growth of the camps4 Humanitarian services in the DP camps5 From representation to autonomy6 Political activism7 A community dedicated to its own dissolution8 Legacy9 See also10 References11 Further reading12 External linksFormation of the DP campsSchool children at Schauenstein DP camp in 1946In an effort to destroy the evidence of war crimes, Nazi authorities and military staff accelerated the pace of killings, forced victims on death marches, and attempted to deport many of them away from the rapidly shrinking German lines. As the German war effort collapsed, survivors were typically left on their own, on trains, by the sides of roads, and in camps. Concentration camps and death camps were liberated by Allied forces in the final stages of the war, beginning with Majdanek, in July 1944, and Auschwitz, in January 1945; Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Mauthausen, and other camps were liberated in April and May 1945.[3]At the time of Germany\'s unconditional surrender on 7 May 1945 there were some 6.5 to 7 million displaced persons in the Allied occupation zones,[4] among them an estimated 55,000 [5] to 60,000[6] Jews. The vast majority of non-Jewish DPs were repatriated in a matter of months.[7] The number of Jewish DPs, however, subsequently grew many fold as Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe migrated westward. It is estimated that a total of more than 250,000 Jewish DPs resided in camps or communities in Germany, Austria, and Italy during the period from 1945 to 1952.[8]In the first weeks after liberation, Allied military forces improvised relief in the form of shelter, food, and medical care. A large number of refugees were in critical condition as a result of malnutrition, abuse, and disease. Many died, but medical material was requisitioned from military stores and German civilian facilities. Military doctors as well as physicians among the survivors themselves used available resources to help a large number recover their physical health. The first proper funerals of Holocaust victims took place during this period with the assistance of Allied forces and military clergy.[citation needed]Shelter was also improvised in the beginning, with refugees of various origins being housed in abandoned barracks, hotels, former concentration camps, and private homes.[citation needed]As Germany and Austria came under Allied military administration, the commanders assumed responsibility for the safety and disposition of all displaced persons. The Allies provided for the DPs according to nationality, and initially did not recognize Jews as constituting a separate group. One significant consequence of this early perspective was that Jewish DPs sometimes found themselves housed in the same quarters with former Nazi collaborators.[9][10] Also, the general policy of the Allied occupation forces was to repatriate DPs to their country of origin as soon as possible, and there was not necessarily sufficient consideration for exceptions; repatriation policy varied from place to place, but Jewish DPs, for whom repatriation was problematic, were apt to find themselves under pressure to return home.[11]General George Patton, the commander of the United States Third Army and military governor of Bavaria, where most of the Jewish DPs resided, was known for pursuing a harsh, indiscriminate repatriation policy.[12][13] However, his approach raised objections from the refugees themselves, as well as from American military and civilian parties sympathetic to their plight. In early July 1945, Patton issued a directive that the entire Munich area was to be cleared of displaced persons with an eye toward repatriating them. Joseph Dunner, an American officer who in civilian life was a professor of political science, sent a memorandum to military authorities protesting the order. When 90 trucks of the Third Army arrived at Buchberg to transport the refugees there, they refused to move, citing Dunner\'s memo. Based on these efforts and blatant antisemitic remarks, Patton was relieved of this command.[14]Harrison reportMain article: Harrison ReportBy June 1945 reports had circulated back in the United States concerning overcrowded conditions and insufficient supplies in the DP camps, as well as the ill treatment of Jewish survivors at the hand of the U.S. Army. American Jewish leaders, in particular, felt compelled to act.[15][16] American Earl G. Harrison was sent by president Truman to investigate conditions among the \"non-repatriables\" in the DP camps. Arriving in Germany in July, he spent several weeks visiting the camps and submitted his final report on 24 August. Harrison\'s report stated among other things that:Generally speaking... many Jewish displaced persons and other possibly non-repatriables are living under guard behind barbed-wire fences, in camps of several descriptions (built by the Germans for slave-laborers and Jews), including some of the most notorious of the concentration camps, amidst crowded, frequently unsanitary and generally grim conditions, in complete idleness, with no opportunity, except surreptitiously, to communicate with the outside world, waiting, hoping for some word of encouragement and action in their behalf.......While there has been marked improvement in the health of survivors of the Nazi starvation and persecution program, there are many pathetic malnutrition cases both among the hospitalized and in the general population of the camps... at many of the camps and centers including those where serious starvation cases are, there is a marked and serious lack of needed medical supplies......many of the Jewish displaced persons, late in July, had no clothing other than their concentration camp garb-a rather hideous striped pajama effect-while others, to their chagrin, were obliged to wear German S.S. uniforms. It is questionable which clothing they hate the more......Most of the very little which has been done [to reunite families] has been informal action by the displaced persons themselves with the aid of devoted Army Chaplains, frequently Rabbis, and the American Joint Distribution Committee......The first and plainest need of these people is a recognition of their actual status and by this I mean their status as Jews... While admittedly it is not normally desirable to set aside particular racial or religious groups from their nationality categories, the plain truth is that this was done for so long by the Nazis that a group has been created which has special needs......Their desire to leave Germany is an urgent one.... They want to be evacuated to Palestine now, just as other national groups are being repatriated to their homes... Palestine, while clearly the choice of most, is not the only named place of possible emigration. Some, but the number is not large, wish to emigrate to the United States where they have relatives, others to England, the British Dominions, or to South America......No other single matter is, therefore, so important from the viewpoint of Jews in Germany and Austria and those elsewhere who have known the horrors of the concentration camps as is the disposition of the Palestine question......As matters now stand, we appear to be treating the Jews as the Nazis treated them except that we do not exterminate them. They are in concentration camps in large numbers under our military guard instead of S.S. troops.[17]Harrison\'s report was met with consternation in Washington, and its contrast with Patton\'s position ultimately contributed to Patton being relieved of his command in Germany in September 1945.[citation needed]Growth of the campsThe number of refugees in the DP camps continued to grow as displaced Jews who were in Western Europe at war\'s end were joined by hundreds of thousands of refugees from Eastern Europe. Many of these were Polish Jews who had initially been repatriated. Nearly 90% of the approximately 200,000 Polish Jews who had survived the war in the Soviet Union chose to return to Poland under a Soviet-Polish repatriation agreement.[18] But Jews returning to their erstwhile homes in Poland met with a generally hostile reception from their non-Jewish neighbors. Between fall 1944 and summer 1946 as many as 600 Jews were killed in anti-Jewish riots in various towns and cities,[19] including incidents in Cracow, around August 20, 1945;[20] Sosnowiec, on October 25; and Lublin, on November 19. Most notable was the pogrom in Kielce on July 4, 1946, in which 42 Jews were killed.[21] In the course of 1946 the flight of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe toward the West amounted to a mass exodus that swelled the ranks of DPs in Germany and Austria, especially in the U.S. Zone.[22]Although hundreds of DP camps were in operation between 1945 and 1948, the refugees were mostly segregated, with several camps being dedicated to Jews. These camps varied in terms of the conditions afforded to the refugees, how they were managed, and the composition of their population.[citation needed]In the American sector, the Jewish community across many camps organized itself rapidly for purposes of representation and advocacy. In the British sector, most refugees were concentrated in the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp and were under tighter control.[citation needed]Humanitarian services in the DP campsThe Allies had begun to prepare for the humanitarian aftermath of the war while it was still going on, with the founding of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), on 9 November 1943. However, the beginnings of the agency were plagued by organizational problems and corruption.[23] The military authorities were, in any case, reluctant to yield significant responsibility for the DP assembly centers to a civilian organization, until it became clear that there would be a need to house and care for the DPs for an extended period of time.[23][24] At the point when it was supposed to begin its work the UNRRA was woefully understaffed in view of the larger than expected numbers of DPs, and additional staff that were hastily recruited were poorly trained.[25] The agency began to send staff into the field in summer 1945; its mission had been conceived mainly as a support to the repatriation process, including providing medical services, and assuring the delivery of adequate nutrition, as well as attending to the DPs\' needs for comfort and entertainment; however, it often fell short of fulfilling these functions.[26] As of 15 November 1945, the UNRRA officially assumed responsibility for the administration of the camps, while remaining generally subordinate to the military, which continued to provide for housing and security in the camps, as well as the delivery of food, clothing, and medical supplies. Over time the UNRRA supplemented the latter basic services with health and welfare services, recreational facilities, self-help programs, and vocational guidance.[27]By the time that the UNRRA took the reins of administration of the camps, the Jewish DPs had already begun to elect their own representatives, and were vocal about their desire for self-governance. However, since camp committees did not yet have any officially sanctioned role, their degree of power and influence depended at first on the stance of the particular UNRRA director at the given camp.[28]The UNRRA was active mainly through the end of 1946 and had wound down its operations by mid 1947. In late 1947 a new successor organization, the International Refugee Organization (IRO) absorbed some of the UNRRA staff and assumed its responsibilities, but with a focus turned toward resettlement, as well as care of the most vulnerable DPs, rather than repatriation.[29]A number of other organizations played an active role in the emerging Jewish community in the DP camps. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (\"Joint\") provided financial support and supplies from American sources; in the British sector, the Jewish Relief Unit acted as the British equivalent to the Joint; and the ORT established numerous vocational and other training.[citation needed]From representation to autonomyThe refugees who found themselves in provisional, sparse quarters under military guard soon spoke up against the ironic nature of their liberation, invoking an oft-repeated slogan \"From Dachau to Feldafing.\" [30] Working committees were established in each camp, and on July 1, 1945 the committees met for a founding session of a federation for Jewish DP camp committees in Feldafing. The session also included representatives of the Jewish Brigade and the Allied military administration. It resulted in the formation of a provisional council and an executive committee chaired by Zalman Grinberg. Patton\'s attempt at repatriating Jewish refugees had resulted in a resolve within the Sh\'erit ha-Pletah to define their own destiny. The various camp committees convened a General Jewish Survivors’ Conference a conference for the entire Sh\'erit ha-Pletah at the St. Ottilien camp attended by delegates representing Holocaust survivors from forty-six Displaced Persons camps in both the American and the British Zones of Occupied Germany and Austria. The delegates passed a fourteen-point program that established a broad mandate, including the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine with UN recognition, compensation to victims, participation in the trials against Nazi war criminals, archival of historical records, and full autonomy for the committees. However, the survivor organizations in the American and British Zones remain separate after the conference and the American and British sectors developed independent organization structures.[31][2][1]The center for the British sector in Germany was at the Bergen-Belsen DP camp, where Josef Rosensaft had been the primus motor for establishing what became the Central Committee for Displaced Persons in the British zone. In the American sector, Zalman Grinberg and Samuel Gringauz and others led the formation of the Central Committee of the Liberated Jews, which was to establish offices first in the former Deutsches Museum and then in Siebertstrasse 3 in Munich.[citation needed]The central organizations for Jewish refugees had an overwhelming number of issues to resolve, among them:Ensuring healthy and dignified living conditions for the refugees living in various camps and installationsEstablishing political legitimacy for themselves by establishing a constitution with a political process with debates, elections, etc.Facilitating and encouraging religious, educational, and cultural expression within the campsArranging for employment for the refugees, though not in enterprises that would contribute to the German economySupporting the absorption in the camp infrastructure of \"new\" refugees arriving from Eastern EuropeResolving acrimonious and sometimes violent disputes between the camps and German policeManaging the public image of displaced persons, particularly with respect to black market activitiesAdvocating immigration destinations for the refugees, in particular to the British Mandate in Palestine, but also the United States, Australia, and elsewhere[citation needed]Military authorities were at first reluctant to officially recognize the central committees as the official representatives of the Jewish refugees in DP camps, though cooperation and negotiations carried characteristics of a de facto acceptance of their mandate. But on September 7, 1946, at a meeting in Frankfurt, the American military authorities recognized the Central Committee of the Liberated Jews as a legitimate party to the issue of the Jewish displaced persons in the American sector.[citation needed]Political activismWhat the people of the Sh\'erit ha-Pletah had in common was what had made them victims in the first place, but other than that they were a diverse group. Their outlook, needs, and aspirations varied tremendously. There were strictly observant Jews as well as individuals that had earlier been assimilated into secular culture. Religious convictions ran from the Revisionist group to Labor Zionists and even ideological communists. Although Yiddish was the common language within the community, individuals came from virtually every corner of Europe.[citation needed]There was lively political debate, involving satire, political campaigns, and the occasional acrimony. The growth of Yiddish newspapers within the camps added fuel to the political culture.[citation needed]The political environment of the community evolved during its years of existence. In the first year or two, it was predominantly focused on improving the conditions in the camps and asserting the legitimacy of the community as an autonomous entity. Over time, the emphasis shifted to promoting the Zionist goals of allowing immigration into the British Mandate in Palestine; political divisions within the Sh\'erit ha-Pletah mirrored those found in the Yishuv itself.[citation needed]At every turn, the community expressed its opposition and outrage against British restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine. In the British sector, the protests approached a level of civil disobedience; in the American sector, attempts were made to apply political pressure to alleviate these restrictions. The relationship between Sh\'erit ha-Pletah and British authorities remained tense until the State of Israel was formed. This came to a head when Lieutenant General Sir Frederick E. Morgan – then UNRRA chief of operations in Germany – claimed that the influx of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe as \"nothing short of a skillful campaign of anti-British aggression on the part of Zion aided and abetted by Russia... [meaning] death to the British.\" (Morgan was allowed to remain in his post after this comment but was fired when making similar comments later).[citation needed]In late 1945, the UNRRA conducted several surveys among Jewish refugees, asking them to list their preferred destination for emigration. Among one population of 19,000, 18,700 named \"Palestine\" as their first choice, and 98% also named \"Palestine\" as their second choice. At the camp in Fürth, respondents were asked not to list Palestine as both their first and second choice, and 25% of the respondents then wrote \"crematorium\". [32]All the while, the Sh\'erit ha-Pletah retained close relationships with the political leadership of the Yishuv, prompting several visits from David Ben-Gurion and other Zionist leaders. While officially detached from the committees, there was considerable support for clandestine immigration to Palestine through the Aliya Beth programs among the refugees; and tacit support for these activities also among American, UNRRA, Joint and other organizations. A delegation (consisting of Norbert Wollheim, Samuel Schlumowitz, Boris Pliskin, and Leon Retter flew to the United States to raise funds for the community, appealing to a sense of pride over \"schools built for our children, four thousand pioneers on the farms... thousands of youths in trades schools... self-sacrifice of doctors, teachers, writers... democratization... hard-won autonomy,\"[33] and also met with officials at the US War Department and Sir Raphael Salento over the formation of the International Refugee Organization.[citation needed]Over time, the Sh\'erit ha-Pletah took on the characteristics of a state in its own right. It coordinated efforts with the political leadership in the Yishuv and the United States, forming a transient power triangle within the Jewish world. It sent its own delegation to the Twenty-Second Zionist Congress in Basel.[citation needed]A community dedicated to its own dissolutionWith the exception of 10,000–15,000 who chose to make their homes in Germany after the war (see Central Council of Jews in Germany), the vast majority of the Jewish DPs ultimately left the camps and settled elsewhere. About 136,000 settled in Israel, 80,000 in the United States, and sizeable numbers also in Canada and South Africa.[8]Although the community established many of the institutions that characterize a durable society, and indeed came to dominate an entire section of Munich, the overriding imperative was to find new homes for the refugees. To make the point, many of the leaders emigrated at the first possible opportunity. Both overt lobbying efforts and underground migration sought to open for unrestricted immigration to Palestine. And the camps largely emptied once the state of Israel was established, many of the refugees immediately joining the newly formed Israel Defense Forces to fight the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[citation needed]The Central Committee in the American sector declared its dissolution on December 17, 1950 at the Deutsche Museum in Munich. Of the original group that founded the committee, only Rabbi Samuel Snieg remained for the dissolution. All the others had already emigrated, most of them to Israel. Rabbi Snieg had remained to complete the first full edition of the Talmud published in Europe after the Holocaust, the so-called Survivors\' Talmud.[citation needed]The last DP camp, Föhrenwald, closed in February 1957, by then populated only by the so-called \"hardcore\" cases, elderly, and those disabled by disease.[citation needed]LegacyWhile most Holocaust survivors view their time in the DP camps as a transitional state, the Sh\'erit ha-Pletah became an organizing force for the repatriation of the remnant in general and to Israel in particular. Its experience highlighted the challenges of ethnic groups displaced in their entirety without recourse to their original homes. It also demonstrated the resolve and ingenuity of individuals who had lost everything but made a new life for themselves.[citation needed]Some struggled with survivor guilt for decades. [34]Suicide amongst survivors has been a subject of some disagreement amongst Israeli medical professionals. In 1947, Dr. Aharon Persikovitz, a gynecologist who had survived the Dachau concentration camp gave a lecture called \"The Psychological State Of the New Immigrant\" in which he said: \"Holocaust survivors do not commit suicide; they heroically prove the continuity of the Jewish people\". According to Professor Yoram Barak this statement became \"an accepted national myth\". Barak says \"The survivors themselves also did not want to be stigmatized as `sick, weak and broken;\' rather, they wanted to join in the myth of the heroic sabra who just recently fought a glorious War of Independence against the enemy.\"[35]

Related Items:

1959 HABRICHA THE ESCAPE SHEERIT HAPLETA JEWISH BOOK 2 VOLS DP CAMPS HOLOCAUST

$75.00