A theory which endows dark matter particles with a rare type of electromagnetism has been strengthened by a detailed analysis performed by a pair of physicists at Vanderbilt University. Professor Robert Scherrer and post-doctoral fellow Chiu Man Ho propose that dark matter, an invisible form of matter that makes up 85 percent of the all the matter in the universe, may be made out of a type of basic particle called the Majorana fermion. The particle’s existence was predicted in the 1930s but has stubbornly resisted detection.

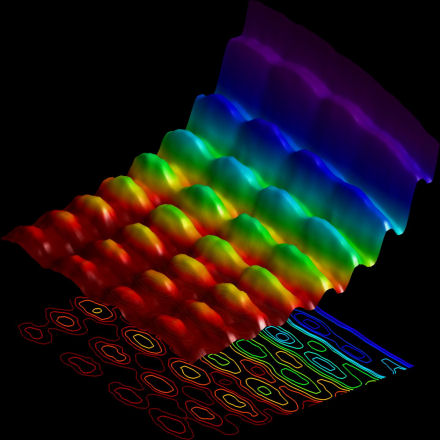

A number of physicists have suggested that dark matter is made from Majorana particles, but Scherrer and Ho have demonstrated that these particles are uniquely suited to possess a rare, donut-shaped type of electromagnetic field called an anapole (top illustration). This field gives them properties that differ from those of particles that possess the more common fields possessing two poles (north and south (bottom), positive and negative (middle)) and explains why all efforts to detect them have so far failed.

“Most models for dark matter assume that it interacts through exotic forces that we do not encounter in everyday life. Anapole dark matter makes use of ordinary electromagnetism that you learned about in school,” said Scherrer. “Further, the model makes very specific predictions about the rate at which it should show up in the vast dark matter detectors that are buried underground all over the world. These predictions show that soon, the existence of anapole dark matter should either be discovered or ruled out by these experiments.”

Fermions are particles like the electron and quark, which are the building blocks of matter. Their existence was predicted by Paul Dirac in 1928. Ten years later, shortly before he disappeared mysteriously at sea, Italian physicist Ettore Majorana produced a variation of Dirac’s formulation that predicts the existence of an electrically neutral fermion. Since then, physicists have been searching for Majorana fermions. The primary candidate has been the neutrino, but scientists have, to date, been unable to determine the basic nature of this elusive particle.

The existence of dark matter was also first proposed in the 1930s to explain discrepancies in the rotational rate of galactic clusters. Subsequently, astronomers have discovered that the rate that stars rotate around individual galaxies is similarly out of sync. Detailed observations have shown that stars far from the center of galaxies are moving at much higher velocities than can be explained by the amount of visible matter that the galaxies contain. Assuming that they contain a large amount of invisible “dark” matter is the most straightforward way to explain these discrepancies.

Scientists hypothesize that dark matter cannot be seen in telescopes because it does not interact very strongly with light and other electromagnetic radiation. In fact, astronomical observations have basically ruled out the possibility that dark matter particles carry electrical charges.

Recently, however, physicists have examined dark matter particles that don’t carry electrical charges, but have electric or magnetic dipoles. The only problem is that even these more complicated models are ruled out for Majorana particles. That is one of the reasons that Ho and Scherrer took a closer look at dark matter with an anapole magnetic moment.

“Although Majorana fermions are electrically neutral, fundamental symmetries of nature forbid them from acquiring any electromagnetic properties except the anapole,” Ho explained. The existence of a magnetic anapole was predicted by the Soviet physicist Yakov Zel’dovich in 1958. Since then it has been observed in the magnetic structure of the nuclei of cesium-133 and ytterbium-174 atoms.

Particles with familiar electrical and magnetic dipoles interact with electromagnetic fields even when they are stationary. Particles with anapole fields don’t. They must be moving before they interact and the faster they move the stronger the interaction. As a result, anapole particles would have been have been much more visible during the early days of the universe and would have become less and less interactive as the universe expanded and cooled.

The anapole dark matter particles suggested by Ho and Scherrer would annihilate in the early universe just like other proposed dark matter particles, and the left-over particles from the process would form the dark matter we see today. But because dark matter is moving so much more slowly at the present day, and because the anapole interaction depends on how fast it moves, these particles would have escaped detection so far – but only just barely.

“There are a great many different theories about the nature of dark matter. What I like about this theory is its simplicity, uniqueness and the fact that it can be tested,” said Scherrer, whose work is detailed in Physics Letters B.

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Modified Newtonian dynamic could do away with dark matter

New blow to dark matter theory

Dark matter not so dark; may be peppered with rogue stars

Comments are closed.