1960 HEBREW Jewish NEWSPAPER BOOK MAGAZINE Design Printing Press JUDAICA Israel For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

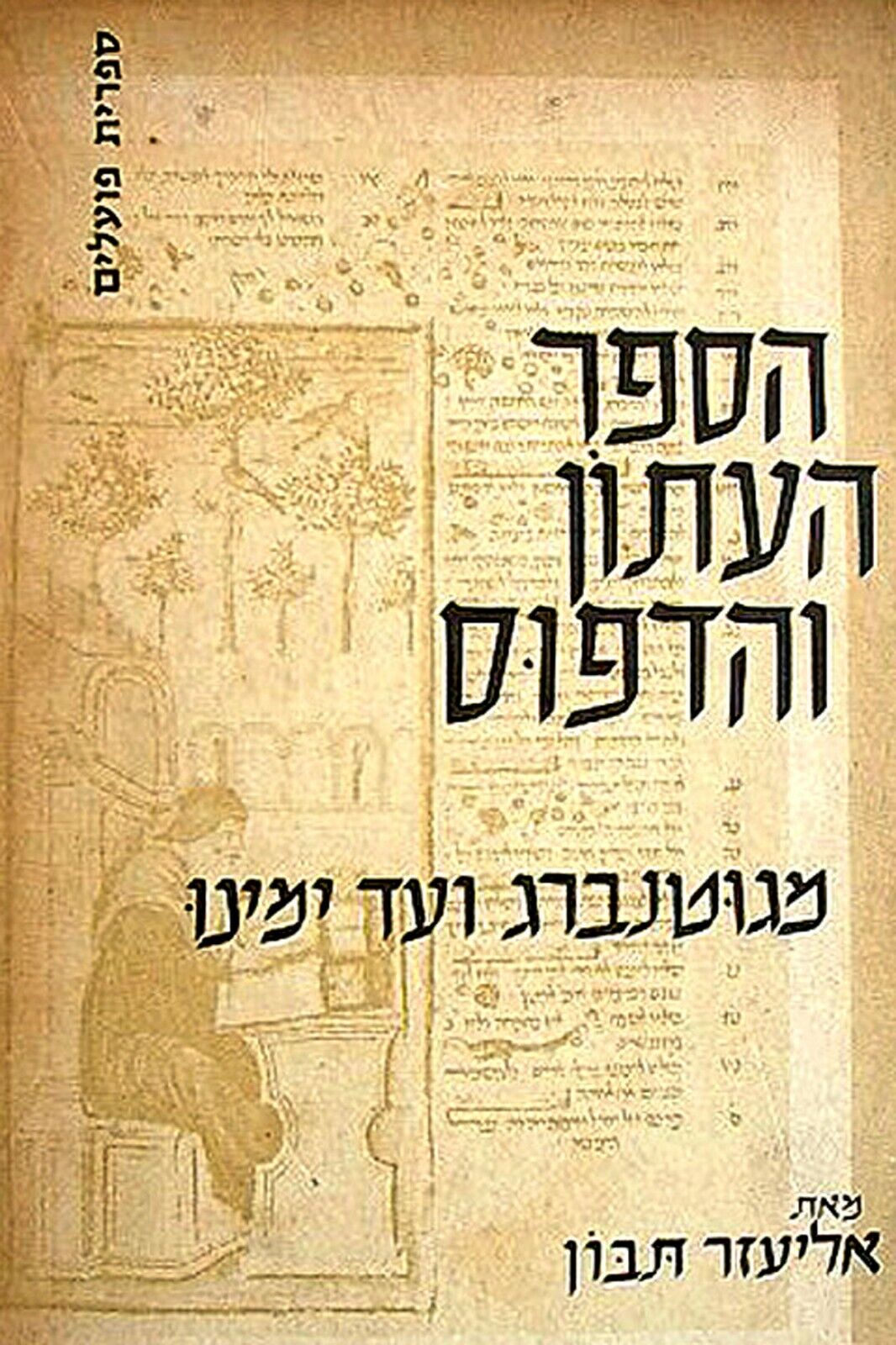

1960 HEBREW Jewish NEWSPAPER BOOK MAGAZINE Design Printing Press JUDAICA Israel:

$69.00

DESCRIPTION : Here for sale is a VERY RARE and RICHLY ILLUSTRATED reference HEBREW BOOK regarding the PRINTING , PRESS and PUBLISHING of BOOKS , MAGAZINES and NEWSPAPERS . The emphasis is obviously on HEBREW books and publications . Thorough study of many relevant issues : The PRESS , The PAPER , The DESIGN , OFF-SET vs LITHOGRAPH , The world of JOURNALS and JOURNALISM , Book ILLUSTRATING , Book DECORATING , PHOTOGRAPHS in BOOKS , The LIBRARY , The BOOK MARKET and MORE and MORE. The book is named \" The BOOK , The NEWSPAPER and the PRINTING-PRESS , From GUTENBERG untill NOWDAYS \" and it was published in Israel in 1960. Original illustrated HC. Cloth spine. No DJ as issued . 9.5 x 7\" . 278 PP. Very good condition. ( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images )Will be sent inside a protective rigid packaging . PAYMENTS :Payment method accepted : Paypal& All credit cards.SHIPPMENT : SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 29 . Book will be sent inside a protective packaging . Handling around 5-10 days after payment.

The first Hebrew periodicals emerged as a result of the European Enlightenment’s influence toward the end of the 18th century on Jewish intellectuals and the modern idea of emancipation. A prominent circle of these intellectuals operated in Prussia, where HaMe’assef, the first Hebrew periodical, was established in Königsberg in 1784. Their ideology attempted to create a bridge between Jewish communities and their surrounding society by disseminating the culture and new values of the Enlightenment. Similar circles operated in other parts of Central and Western Europe; a few were also active in the East. They advocated ending the conservative religious monopoly on education; expanding the study of secular and scientific subjects; abandoning characteristic Jewish occupations, such as peddling, in favor of industrial or agricultural work; and more. Among other things, these intellectuals rejected the use of Yiddish (the Jewish language used specifically by Ashkenazi communities) and supported adopting the local national language. However, they considered Hebrew legitimate both as a holy tongue and as the language of Jewish high culture over the course of history, and they adopted it for use in their publications and initial efforts to prepare Jews for the demands of modern society. Beginning in the late 18th century, as a result, the first periodicals of what is now known as the Haskalah, or the Jewish Enlightenment, were published in Hebrew. The early maskilic Hebrew periodicals focused on literary and educational content, catered to a very limited audience, and were short-lived. Jewish journalism in general did not flourish until almost the 1940s; it was only then that Jewish periodicals and newspapers began to multiply in Central and Western Europe. However, these papers already reflected the process of acclimating to local culture and were written in local national languages: German, English, French, Hungarian, etc. The growth of Hebrew journalism gathered momentum only when the Haskalah movement expanded in Eastern Europe, home to the majority of the world’s Jewish population. The processes of acclimation to the local Slavic cultures were different than in other European regions, and Hebrew did not quickly fall out of use. A relatively large number of Hebrew readers existed, and it began to develop as a modern language. As a result, during the 1850s Hebrew newspapers and periodicals began to be published that emphasized news reports and enjoyed a long lifespan ( Ha-Magid, Ha-Melitz, and more). These new media were used not only by the Hebrew maskilic stream of Judaism, but also by the competing stream, the Haredi Orthodox movement (Ha-Levanon). When the seeds of Jewish nationalism began to appear, several maskilic newspapers sided with the new movement, and new papers were founded supporting its ideology. The development of the small Jewish community in Palestine as an ideological center was also expressed in the development of the Hebrew press there (Ha-Levanon, Habazeleth, and Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s newspapers). Because it used the “holy tongue” common to Jewish communities throughout the world, Hebrew journalism was an extremely effective instrument in encouraging modern communication between those scattered communities -- exchanging information, encouraging projects for mutual aid, and publicizing the platforms of new movements that were developing in different regions. The existence of Hebrew journalism also encouraged public development not only in European communities, but outside Europe as well. Local correspondents from around the world sent news stories to Hebrew newspapers and participated in the debates that took place in their pages. This section includes a few newspapers whose publication continued into the 20th century, while the majority of their issues appeared in the 19th century. An exception to this rule is Ha-Zman which was published in its entirety in the beginning of the 20th century. Newspapers in this section: Ha-Magid Ha-Modia Ha-Levanon Ha-Zvi Ha-Zman Ha-ZefiraHa-Melitz Ha-Micpe Hashkafa Habazeleth Ivri Anoch Mahziqey Ha-Dat / Qol Mahziqey Ha-Dat For a significant, albeit brief, period in modern Jewish history, in the interwar era, more newspapers were published in Yiddish than in any other language in the Jewish world. This was the climax of a long process. The Yiddish press developed in a convoluted manner, with twists and turns: a difficult beginning in the second half of the 19th century, followed by a speedy, impressive development at the start of the twentieth, before its tragic demise in Eastern Europe due to the Holocaust, as well as a slow decline in other Yiddish-speaking countries. The main causes of this drastic and swift contraction in the scope of the Yiddish press were external: the physical extermination of the Yiddish speaking communities of Eastern Europe by the Nazis, and the destruction of Yiddish culture in the Soviet Union. However, the decline of Yiddish must also be attributed to other, internal and long-term factors. Yiddish was the spoken language of most Eastern European Jews in their homeland as well as in their new countries, both before and after the Holocaust. Yet rising secularization and growing linguistic assimilation into the larger society undermined the status of this unique Jewish language in the modern world. In this respect, mass immigration to the west was a double-edged sword. Over the course of two or three generations Yiddish speakers flocked to large cities in the Western World, creating large communities with unprecedented numbers of Yiddish speakers, but linguistic assimilation soon curtailed the viability of the once-vibrant language. From a different angle, Zionism considered Yiddish an impediment to the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language. The fate of the Yiddish press thus embodies one of the richest and most complex chapters in the history of modern Jewish culture. The first Yiddish weekly in Czarist Russia, Kol mevaser (1862-1873) was published in Odessa. Like most of the Jewish newspapers of the time, its articles and literary material were more prominent than its news coverage. It was in this weekly that S.Y. Abramovitsh, better known as Mendele moykher-sforim, published his first work in Yiddish, whose date of publication – 1864 – marks the beginning of modern Yiddish literature. Kol mevaser set indeed a precedent: Yiddish press has always served as a home for Yiddish literature, especially for prose, starting with S.Y. Abramovitsh, through Sholem Aleichem and Y.L. Peretz, all the way to Isaac Bashevis Singer. When Kol mevaser folded it left a void that was not quickly filled. Only in 1881 was a new Yiddish weekly published in Czarist Russia, Yidishes folks-blat, and when it too closed down in 1890, there was once again a break in the continuity of the Yiddish press in Eastern Europe. However, in these years its new center gradually took shape. In 1881, when the Jewish migration to America began, a first attempt was made to publish a daily Yiddish newspaper in New York, Yidishes tageblat. Although this first effort was unsuccessful, two years later it renewed publication, which lasted until 1928. Its conservative stance and avowed loyalty to Orthodox Judaism did not prevent this newspaper from printing sensational material of various kinds. The highly diverse ideological leanings of Eastern European Jewish immigrants in America found their expression quite early in the Yiddish press. The 1890s witnessed the first Yiddish periodicals that served as platforms for socialism and anarchism – weeklies, monthlies, and even daily newspapers. In 1892 the monthly Di tsukunft was put in print. At first it sought to disseminate socialist and radical ideas as well as popular science, but in later years it became the central Yiddish literary journal worldwide. In 1897 the daily Forverts was launched in New York under the editorship of Abraham Cahan, espousing an explicit socialist ideology. Its early years were rather modest, and for a while its existence was in question when its editor left office, but upon his return the newspaper grew impressively. Cahan’s ability to balance the official socialist ideology with his sensitivity to the various needs of the immigrant masses transformed Forverts into the leading and most successful Yiddish newspaper of all time. Its circulation and scope reached their apogee in the 1920s. However, the severe restrictions upon immigration to the United States, which came into effect in 1924, closed the gates for Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Eventually this sealed the fate of the American Yiddish press. Towards the beginning of the twentieth century, new possibilities opened for the Yiddish press in Czarist Russia. The weekly Der yud (1899-1902) combined its Zionist ideology with a marked interest in the development of Yiddish literature. It published a variety of writers, from the classics – Mendele moykher-sforim, Y. L. Peretz, and Sholem Aleichem – to younger writers. In 1903 this journal made way for Der fraynd, the first Yiddish daily in Czarist Russia. It was first released in St. Petersburg and moved later to Warsaw, where it lasted until 1914. Warsaw, which boasted the largest Jewish community in Europe, soon became the capital of the Yiddish press. Between 1908 and 1910, two newspapers were launched there – Haynt and Der Moment . Both of them garnered immediate popularity and were published until the early days of World War II. Despite their relatively limited means, these were highly dynamic publications. They included a mixture of news items, opinion columns on current Jewish topics, and literary works of different kinds – mainly short stories and novels in installments, both by well-known and established writers, as well as those of a sensationalist character which catered to a popular audience. The 1920s and 1930s were the heyday of Yiddish press worldwide. Roughly fifty daily newspapers were published in many countries – Argentina, Canada, England, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Soviet Union, the United States, and Uruguay. Alongside the daily newspapers, the Yiddish press comprised an impressive number of weeklies published in dozens of cities, as well as monthlies and journals of irregular frequency. They covered all areas of interest for the Yiddish reading public – current affairs, ideological questions and party politics, literature, theater, professional issues, education, children’s newspapers et al. In smaller Yiddish-speaking communities, such as South Africa and Australia, weeklies served as a mouthpiece for the promotion and discussion of communal issues. Every ideological camp in the Jewish world endeavored to have its own publication wherever Yiddish speakers were present in significant numbers. Thus Yiddish journalism reflected a variety of opinions and views – Orthodoxy, different brands of Zionism, the “Bund,” anarchism, and communism. By sheer number of publications, Poland led the way, while New York\'s daily press was ahead in terms of circulation and scope. The Warsaw Yiddish daily press included, besides Haynt and Der moment, the Bundist daily Folkstsaytung, an Orthodox newspaper and several tabloids. In the 1930s four dailies were published in New York: Forverts, committed to socialism, nominally at least; Der tog, which provided a platform for a wide range of views on Jewish issues; the more conservative Der morgen zhurnal; and the communist Morgn frayheyt. The Soviet Union was the only Yiddish cultural center of those years whose newspapers had to follow the official political line. Both the scope of Jewish cultural life in this country and its press started to decline towards the end of the thirties. Following the war years and the Holocaust, mere traces remained of the Soviet Yiddish press, which was finally wiped out by the authorities in 1948. After a hiatus of several years, the monthly Sovetish Heymland (1961-1991) was issued in Moscow. Most works of Yiddish writers printed in this journal had to toe the current ideological approach, and they reflected a rather conservative literary taste. The attempt to keep the journal in a new form after the collapse of Soviet rule proved unsuccessful. In the wake of the Holocaust new Yiddish publications were established for and by the survivors, mainly in Poland and in the Displaced Persons camps in Germany and elsewhere. However, the scale of these publications gradually decreased, both as a result of the waves of post-war Jewish emigration from Eastern Europe and due to the communist takeover in Poland, which put an end to the journals published by different Jewish parties. The Yiddish press was still vibrant in the 1950s and 60s, numbering about fourteen daily newspapers in Argentina, Canada, France, the United States, and Uruguay. In addition, an impressive range of Yiddish journals were published in Israel, including the daily newspaper Letste nayes, weeklies and monthlies sponsored by various parties, and last but not least the quarterly Di goldene keyt (1949-1995), the central literary publication of the Yiddish world in the post-Holocaust era. The world of the Jewish book is as great and rich as the world of Judaism itself. From the earliest handwritten scrolls to today\'s computer typesetting, the story of the Jewish book is a story of people communicating across continents and generations. Wherever the Jewish people have dwelled, the scribe and the printer have followed the teacher and the Rabbi so that the learning process could continue. The invention of printing was a unique event in the history of the Mesora, (the transmission of Jewish traditions from Sinai to present times). A change in information technology which happened outside the Jewish world, had a profound effect on the methodology of Torah study. The invention of printing came at a most fortuitous time. With the scattering of Spanish Jewry across Europe and around the Mediterranean following the Spanish expulsion in 1492, there was a traumatic break in the smooth flow of the Mesora, effectively closing the era of the Early Commentators. The invention of printing softened this blow by providing the means whereby communities in exile could consult with the great leaders of earlier generations through their writings. Rabbinic leaders were highly enthusiastic about the new technology. The craft of printing was considered an Avodat HaKodesh - holy work, and the printing press was likened to an alter. A later commentator (Maharit Chayot - Germany 19th century) compared it to the art of \"writing with many pens\" referred to in the second temple in Tractate Yuma 38b. The first book printed entirely in Hebrew letters, Rashi\'s commentary on the Pentateuch was printed in Rome about 1470, only 14 years after Gutenberg printed his bible. Within a decade Hebrew printing had spread from Italy to Spain and Constantinople with the press of Gerson and Joshua Solomon at Soncin near Cremona being the most active. Here are a few landmark dates and events in early Hebrew printing: 1475 - First dated Hebrew work is printed in Reggio di Calabria 1482 - First Spanish Hebrew book printed in Guadaljara 1492 - Expulsion from Spain and destruction of Hebrew books 1503 - David Nahmias begins printing in Constantinople 1512 - Beginning of Hebrew printing in Salonika 1475 - 1530 The Soncinos print in Mantua, Naples, Brescia, Cassal Maggiore, Barca, Fano, Pesaro, Ortona, Rimini and Constantinople 1513 - Press of Gershon Solomon Cohen in Prague prints prayer book 1520 - Daniel Bomberg of Venice prints the first complete Talmud edition. The Venice community sends a copy to Henry VIII of England as a gift 1533 - Hayim ben David Schwartz moves his press from Prague to Augsburg Germany 1542 - Beginning of censorship of Hebrew books by the Roman Curia 1550 - Giustiniani and Bragadini enter into competition with Bomberg in Venice 1554 - The burning of the Talmud at Ferrara and closing of the Venice printers 1556 - First edition of Zohar is saved in Mantua but Zioni commentary is burned1565 - Printing resumes in Venice and first edition of Shulkan Aruch appears 1569 - Isaac ben Aaron of Prossnitz prints in Cracow 1578 - The Talmud begins to appear in Basel 1627 - Gutel the daughter of Leb Setzer prints in Prague 1627 - Menasheh ben Israel and Daniel De Fonseca begin printing in Amsterdam 1658 - Uri Phoebus begins printing in Amsterdam and in Zolkiev in 1692 1697 - Jacob Proops begins printing in Amsterdam. By 1700 dozens of Hebrew presses were continuously active in Eastern Europe, Italy, and the Mediteranean Countries and printing continued in Western Europe in Germany itself even as late as 1940. The Nazi destruction of Jewish civilization in Europe included not only the murder of Jewish people but the erasing of Jewish culture by burning Jewish books in synagogues, libraries, and homes. During WWII refugees printed Hebrew books in such exotic locations as Beirut, Johannesburg, Harbin and Shanghai but the great centers of Hebrew printing continued to migrate until today they are in New York and Jerusalem, both of which were unknown for Hebrew publishing in the 18th century. From the year 1850 the introduction of inexpensive pulp based papers brought about a further revolution in Hebrew publishing. Printing and owning books were no longer the prerogative of the wealthy, now the middle class could also afford to acquire Sifrei Kodesh. Publishing societies printed hundreds of unpublished works from manuscripts, new editions of early imprints, journals and newspapers blossomed, new collections of contemporary Responsa and commentaries appeared in every Jewish community...... The blessing of cheap paper brought a curse in disguise. The acids used to break down wood chips into pulp continue to acidify the paper matrix causing it after several decades it to turn brown, brittle and crack. Many important works from the last generation are no longer usable, they are simply disintegrating into piles of brown flakes. The following quote is from the Judaica Archival Project application to the brittle book initiative of the National Endowment For The Humanities. In correspondence and conversations we have had with the librarians of the major Judaica libraries in the world we have found unanimous agreement that brittle 19th century printed Rabbinic works are one of the most pressing issues on every Jewish Research library\'s preservation agenda. 1552

Related Items:

THEODOR HERZL DIARIES FATHER OF ZIONISM ISRAELI STATE 1960 HARDCOVER 5 VOLUMES

$1850.00

Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov 1960 Yiddish Hebrew Judaica Lit

$40.00

hebrew coca cola circa 1960 brand print

$220.00