How closely does the relationship between people and their dogs mirror the parent-child relationship? A new study has been investigating differences in how parts of the brain are activated when women view images of their children and of their own dogs. The researchers, from Massachusetts General Hospital, have detailed their findings in the journal PLOS ONE.

“Pets hold a special place in many people’s hearts and lives, and there is compelling evidence from other studies that interacting with pets can be beneficial to the physical, social and emotional wellbeing of humans,” says Lori Palley, co-lead author of the report. “Several previous studies have found that levels of neurohormones like oxytocin rise after interaction with pets, and new brain imaging technologies are helping us begin to understand the neurobiological basis of the relationship, which is exciting.”

In order to compare patterns of brain activation involved with the human-pet bond with those elicited by the maternal-child bond, the study enrolled a group of women with at least one child aged 2 to 10 years old and one pet dog that had been in the household for two years or longer.

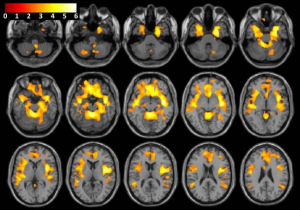

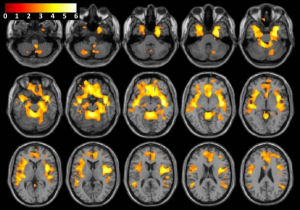

Next, functional magnetic resonance imaging was carried out as the participants lay in a scanner and viewed a series of photographs. The photos included images of each participant’s own child and own dog alternating with those of an unfamiliar child and dog belonging to another study participant.

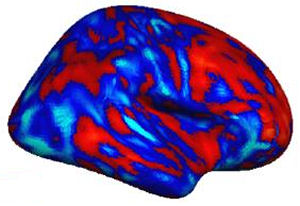

The imaging revealed both similarities and differences in the way important brain regions reacted to images of a woman’s own child and own dog. Areas previously reported as important for functions such as emotion, reward, affiliation, visual processing and social interaction all showed increased activity when participants viewed either their own child or their own dog.

A region known to be important to bond formation – the substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area – was activated only in response to images of a participant’s own child.

Interestingly, the fusiform gyrus, which is involved in facial recognition and other visual processing functions, actually showed a greater response to own-dog images than own-child images.

“The results suggest there is a common brain network important for pair-bond formation and maintenance that is activated when mothers viewed images of either their child or their dog,” says Luke Stoeckel, co-lead author of the PLOS ONE report. “We also observed differences in activation of some regions that may reflect variance in the evolutionary course and function of these relationships. We think the greater response of the fusiform gyrus to images of participants’ dogs may reflect the increased reliance on visual than verbal cues in human-animal communications.”

The investigators caution that further research is needed to replicate these findings in a larger sample and to see if they are seen in other populations – and in relationships with other animal species. Based on their initial findings, the research team suggest that functional neuroimaging may one day provide a fuller explanation for the complexities underlying human-animal relationships.

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Domestication of dogs may explain success of early humans

Customizing animal scents to manipulate animal behaviors

MRI scans predict pop music success

This Is Your Brain On Jazz

Comments are closed.