The first study, from the United States Geological Survey, looks at global shifts in water availability using stream-flow measurement archives from 165 locations around the world and an ensemble of global climate models.

While water availability is directly related to climate, there is no simple relationship for all regions between future temperatures and future water resources. Some regions may experience increases in precipitation and run-off while other regions may experience decreases.

“A warmer atmosphere can carry more water. So, warmer winds can deliver more water to a region, but they can also take more away. This give-and-take plays out differently in different parts of the world, causing decreases in water supply here, and increases there,” explained Christopher Milly, lead author of the study. The study concludes by warning that changes in sustainable water availability could have considerable regional-scale consequences for economies as well as ecosystems.

The second study, conducted by researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, examined the impact that shrinking glaciers and disappearing snow areas will have on fresh water supplies, concluding that the ensuing water shortages will impact millions of people around the world.

The study says that the forces driving these changes – described as “greenhouse physics” – show that in a warming climate more water will fall in the form of rain rather than snow, filling reservoirs to capacity earlier than normal. Additionally, a warming climate will result in snow melting earlier in the year, disrupting the traditional timetable of run-off streams. These changes mean less snow accumulation in the winter and earlier snow-derived water run-off in the spring, challenging the capacities of existing water reservoirs. Water shortages will occur in areas where reservoir capacity cannot hold the increased run-off.

Researcher Tim Barnett said some areas will be hit harder than others. “California, and in particular the Columbia Basin, doesn’t have enough dam capacity to hold a seasonal cycle of water,” explained Barnett. “When you change the seasonality of how rivers flow you are essentially putting the water runoff all into spring rather than being able to draw it out through summer. When the water comes out all at once there isn’t enough capacity to contain it.”

For Canada, the study suggests that earlier spring water runoff will threaten agricultural production in the Canadian Prairies. In Europe, climate warming in the Rhine River Basin may reduce peak-demand water availability for industrial applications, agriculture and household uses. Ship transportation, flood protection, hydropower generation and revenue from skiing all could be threatened as a result.

The new study follows on from Barnett’s earlier research which showed that vital water resources derived from the Sierra Nevada may suffer a 15- to 30-percent reduction in the 21st century as a result of changes in snowpack runoff. The new study extended these ideas to regions that depend on glacier-derived water for their main dry season water supply. Such regions contrast with those that depend on water derived from snowpack, such as the western U.S., where water supplies are replenished each year. Thus, the researchers warn that “even more serious problems may occur” in glacier dependent regions “because once the glaciers have melted in a warmer world, there will be no replacement for the water they now provide.”

It seems that Asia might be at most risk from retreating glaciers. Barnett believes China, India and other parts of Asia will be particularly impacted due to their high populations and the fact that the ice mass in the mountainous area of this region is the third largest on Earth.

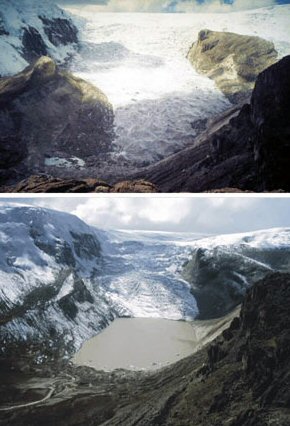

In South America, a large part of the population west of the Andes Mountains could be at a similar risk due to shrinking supplies of glacier-derived river water. Glacier-covered areas in Peru (pictured above in 1978 and 2002), have experienced a 25 percent reduction in the past three decades, the study notes, and “at current rates some of the glaciers may disappear in a few decades, if not sooner.”

“Climate warming is a certainty in our future and the bottom line in this analysis is that we looked at the impact of the warming and the long-term prognosis is clear and very dire,” warned Barnett. “It’s especially clear that regions in Asia and South America are headed for a water supply crisis.”

Pic courtesy: Professor L. Thompson

Sources: United States Geological Survey, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California

Comments are closed.