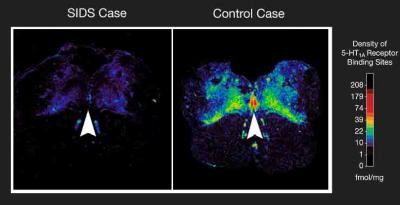

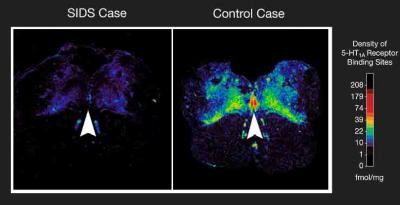

Researchers from the Children’s Hospital Boston say they have the strongest evidence yet that sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is not a “mystery” disease, and in fact has a concrete biological basis. Published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the study documented abnormalities in the brainstem of babies who died from SIDS.

Past studies have identified various risk factors for SIDS, such as putting babies to sleep on their stomachs, but until now there has been little understanding of SIDS’s biologic basis. The new insights came about thanks to brain autopsy specimens from infants who had died from SIDS; specifically, the lowest part of the brainstem, known as the medulla oblongata, which controls breathing, blood pressure and body heat. The researchers say they found abnormalities in serotonin levels there, a chemical that transmits messages from one nerve cell to another.

The medulla oblongata’s serotonin system helps coordinate breathing, blood pressure, sensitivity to carbon dioxide, and temperature during waking and sleep. When babies sleep face-down or have their faces covered by bedding, they are thought to re-breathe exhaled carbon dioxide, therefore breathing in less oxygen. Normally, the rise in carbon dioxide activates nerve cells in the brainstem, which in turn stimulate respiratory and arousal centers in the brain so that the baby doesn’t asphyxiate. “A normal baby will wake up, turn its head, and start breathing faster when carbon dioxide levels rise,” explained researcher Hannah Kinney. But in babies who die from SIDS, defects in the serotonin system may impair these reflexes, she added.

The findings also provide a biological explanation for why SIDS occurs twice as often in males than females – male SIDS infants had significantly fewer of a particular type of serotonin receptor than female SIDS infants. Serotonin abnormalities also help explain why infants under 6 months are most vulnerable to SIDS. At birth, babies must adjust from being totally dependent on their mother to breathing on their own and maintaining their own blood pressure. If the brainstem serotonin system is defective or still immature, this transition to total independence in the control of vital functions may be impaired during the crucial first six months of life. “We think that the control systems for vital or homeostatic functions reach full maturity only towards the end of the first year of life,” Kinney says.

The findings also provide a biological explanation for why SIDS occurs twice as often in males than females – male SIDS infants had significantly fewer of a particular type of serotonin receptor than female SIDS infants. Serotonin abnormalities also help explain why infants under 6 months are most vulnerable to SIDS. At birth, babies must adjust from being totally dependent on their mother to breathing on their own and maintaining their own blood pressure. If the brainstem serotonin system is defective or still immature, this transition to total independence in the control of vital functions may be impaired during the crucial first six months of life. “We think that the control systems for vital or homeostatic functions reach full maturity only towards the end of the first year of life,” Kinney says.

The researchers speculate that the abnormalities they observed begin during early fetal development, and that prenatal affronts like maternal smoking and alcohol use may adversely affect development of the brainstem serotonin system during this time. While more research is needed to explain exactly what causes the abnormalities and how they can be prevented, Kinney and her colleagues hope to develop a diagnostic test to identify infants at risk for SIDS. They also envision a drug or other type of treatment to protect infants who have abnormalities in their brainstem serotonin system.

Source: Children’s Hospital Boston

Graphic courtesy David Paterson, Ph.D., Children’s Hospital Boston

Comments are closed.