In a recent development in bionics, scientists have replicated a powerful feature of the humble cricket that could lead to a new generation of cochlear implants, among other applications. The tiny hairs found on body parts of crickets are one of nature’s most sensitive sound detectors. This is a lucky thing for the cricket, because the hair sensors allow the cricket to escape before any predator gets too close. Published in yesterday’s (20th June 2005) Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering, an Institute of Physics journal, this research will help scientists understand the complex physics that crickets use to perceive their surroundings.

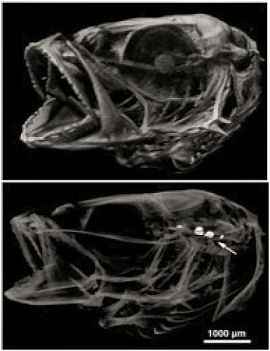

Crickets are mostly earth bound creatures, which makes them vulnerable to wandering and flying predators. Fortunately, nature endowed crickets, like the wood cricket Nemobius sylvestris, with a pair of hairy appendages at the abdominal end of their body called cerci, which are incredibly good at detecting small fluctuations in air currents – such as the beating of a wasp’s wings or the jump of an attacking wolf spider. With each hair independently socket mounted, airflow causes a drag force on the hair rotating its base and firing specific neural cells. In this way the cricket can pinpoint low-frequency sound from any given direction by using the combined neural information from all the sensory hairs on the cerci.

Actual cricket hairs are incredibly energy efficient sensors, and crickets are thought to perceive flows with energies as small as or even below thermal noise levels (the background “noise” caused by the Brownian motion of particles). The cricket hair canopy also shows outstanding directivity, since acoustic flow, in contrast to acoustic pressure, not only has a magnitude but also a direction. The team are now working on newer generations of hairs, which they expect to deliver sensitivities at least one order better than their recent attempts. Marcel Dijkstra, a member of the Twente team, said: “These sensors are the first step towards a variety of exciting applications as well as further scientific exploration. We could use them to visualise airflow on surfaces, such as an aircraft fuselage.” In a more advanced stage, the structures may form a stepping-stone towards the fabrication of hairs operating in fluids, such as found in the inner ears of mammals.

Comments are closed.