By re-examining contemporary human language, MIT researchers believe they can uncover how human communication could have evolved from the systems underlying the older communication modes of birds and primates.

“How did human language arise?” asks linguist Shigeru Miyagawa, a Professor of Japanese Language and Culture at MIT. “The best we can do is come up with a theory that is broadly compatible with what we know about human language and other similar systems in nature.”

As an example, he cites the Indonesian silvery gibbon, which exhibits a behavior that’s unusual for a primate – it sings. It can vocalize long, complicated songs, using 14 different note types that signal territory and send messages to potential mates and family.

From birds, he contends, we derived the melodic part of our language, and from other primates, the pragmatic, content-carrying parts of speech. Sometime within the last 100,000 years, he believes those capacities fused into the form of human language that we know today.

Miyagawa believes that some apparently infinite qualities of modern human language, when reanalyzed, actually display the finite qualities of languages of other animals – meaning that human communication is more similar to that of other animals than we generally realized.

Specifically, he explains, animals have finite sets of things they can express; human language is unique in allowing for an infinite set of new meanings. “Human language is unique, but if you take it apart in the right way, the two parts we identify are in fact of a finite state,” Miyagawa says. “Those two components have antecedents in the animal world. According to our hypothesis, they came together uniquely in human language.”

Miyagawa’s new study, published in Frontiers in Psychology , builds on his earlier work which argued that human language consists of two distinct layers: the expressive layer, which relates to the mutable structure of sentences, and the lexical layer, where the core content of a sentence resides.

The expressive layer and lexical layer have antecedents, the researchers believe, in the languages of birds and other mammals, respectively. For instance, in another paper published last year, Miyagawa presented a broader case for the connection between the expressive layer of human language and birdsong, including similarities in melody and range of beat patterns.

Birds, however, have a limited number of melodies they can sing or recombine, and nonhuman primates have a limited number of sounds they make with particular meanings. That would seem to present a challenge to the idea that human language could have derived from those modes of communication, given the seemingly infinite expression possibilities of humans.

But the researchers think certain parts of human language actually reveal finite-state operations that may be linked to our ancestral past. Consider a linguistic phenomenon known as “discontiguous word formation,” which involve sequences formed using the prefix “anti,” such as “antimissile missile,” or “anti-antimissile missile missile,” and so on. Some linguists have argued that this kind of construction reveals the infinite nature of human language, since the term “antimissile” can continually be embedded in the middle of the phrase.

However, as the researchers argue in the new paper, “This is not the correct analysis.” The word “antimissile” is actually a modifier, meaning that as the phrase grows larger, “each successive expansion forms via strict adjacency.” That means the construction consists of discrete units of language. In this case and others, Miyagawa says, humans use “finite-state” components to build out their communications.

“The complexity of such language formations doesn’t occur in birdsong, and doesn’t occur anywhere else, as far as we can tell, in the rest of the animal kingdom,” observes co-researcher Robert Berwick, a professor of computational linguistics at MIT. “Indeed, as we find more evidence that other animals don’t seem to posses this kind of system, it bolsters our case for saying these two elements were brought together in humans.”

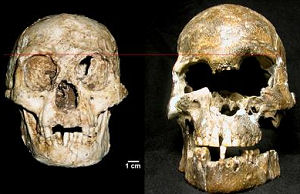

The researchers acknowledge their hypothesis is a work in progress. After all, Charles Darwin and others have explored the connection between birdsong and human language. Now, Miyagawa says, the researchers think that “the relationship is between birdsong and the expression system,” with the lexical component of language having come from primates. Indeed, as the paper notes, the most recent common ancestor between birds and humans appears to have existed about 300 million years ago, so there would almost have to be an indirect connection via older primates – even possibly the silvery gibbon.

The researchers are still exploring how these two modes could have merged in humans, but the general concept of new functions developing from existing building blocks is a familiar one in evolution. “You have these two pieces,” explained Berwick. “You put them together and something novel emerges. We can’t go back with a time machine and see what happened, but we think that’s the basic story we’re seeing with language.”

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Inaccuracy of brain’s language processing revealed

Say what? Ambiguity makes language more efficient

Couples’ language use predicts relationship success

Emotional content of books diverging by country, say language sleuths

Comments are closed.