Field tests by University of California – Davis scientists have shown conclusively that rising levels of carbon dioxide inhibit plants’ ability to assimilate nitrates into proteins. The findings, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, indicate that the nutritional quality of food crops such as wheat, barley, rice, and potatoes is at risk as climate change intensifies. Wheat alone provides about a quarter of all protein in the global human diet.

“Food quality is declining under the rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide that we are experiencing,” said the study’s lead author Arnold Bloom. “Several explanations for this decline have been put forward, but this is the first study to demonstrate that elevated carbon dioxide inhibits the conversion of nitrate into protein in a field-grown crop.”

The assimilation of nitrogen plays a key role in plants’ growth and productivity. In food crops, it is especially important because plants use nitrogen to produce the proteins that are vital for human nutrition.

Previous laboratory studies had demonstrated that elevated levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide inhibited nitrate assimilation in the leaves of grain and non-legume plants; however there had been no verification of this relationship in field-grown plants.

To observe the response of wheat to different levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, the researchers examined samples of wheat that had been grown in 1996 and 1997 at the Maricopa Agricultural Center in Arizona.

At that time, carbon dioxide-enriched air was released in the fields, creating an elevated level of atmospheric carbon at the test plots, similar to what is now expected to be present in the next few decades. Control plantings of wheat were also grown. Leaf material harvested from the various wheat plots was immediately dried and stored. More than a decade later, Bloom and the research team were able to conduct chemical analyses that were not available at the time the experimental wheat plants were harvested.

The researchers found that three different measures of nitrate assimilation confirmed that the elevated level of atmospheric carbon dioxide had inhibited nitrate assimilation into protein in the field-grown wheat.

“These field results are consistent with findings from previous laboratory studies, which showed that there are several physiological mechanisms responsible for carbon dioxide’s inhibition of nitrate assimilation in leaves,” Bloom said.

On a global scale, Bloom says the findings indicate that the overall amount of protein available for human consumption may drop by about 3 percent over the next few decades. While heavy nitrogen fertilization could partially compensate for this decline in food quality, it would also have negative consequences including higher costs, more nitrate leaching into groundwater, and increased emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide.

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Modern crops’ lack of adaptability threatens global food chains

Mammals may shrink with warming climate

Crop pests relentless in their march polewards

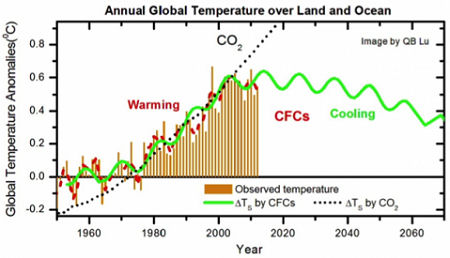

CO2 not to blame for global warming, claims new study that argues global cooling has already begun

Comments are closed.