Lynne Isbell, a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Davis, originally put forward the theory in her 2006 book The Fruit, the Tree, and the Serpent. In the book, she argued that our primate ancestors evolved precise, close-range vision primarily to spot and avoid dangerous snakes.

Isbell’s book explains that modern mammals and snakes big enough to eat them evolved at about the same time, 100 million years ago. Venomous snakes are thought to have appeared about 60 million years ago – “ambush predators” that have since then shared the trees and grasslands with primates.

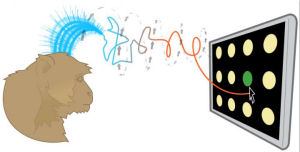

The new study, led by neuroscientists Hisao Nishijo and Quan Van Le at Toyama University (Japan), shows that there are specific nerve cells in the brains of rhesus macaque monkeys that strongly respond to images of snakes.

Nishijo’s lab studies the neural mechanisms responsible for emotion and fear in rhesus macaque monkeys. In this case, instinctive responses that occur without learning or memory. The monkeys tested in the new study were reared in a walled colony and had not previously encountered a snake.

“The snake-sensitive neurons were more numerous, and responded more strongly and rapidly, than other nerve cells that fired in response to images of macaque faces or hands, or to geometric shapes,” said Nishijo. “The results show that the [macaque] brain has special neural circuits to detect snakes, and this suggests that the neural circuits to detect snakes have been genetically encoded.”

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Torturous terrain behind human bipedal evolution?

False memories implanted in mammalian brain

Stunning new species of palm-pitviper discovered

“Nanosponge” removes toxins from bloodstream

Comments are closed.