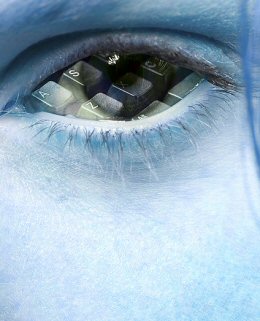

In work that could lead to much-improved computer vision systems, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) neuroscientists have tricked the visual cortex into confusing one object with another, thereby demonstrating that time teaches us how to recognize objects.

Because an object such as a cat can produce innumerable different impressions on the retina – depending on the direction of gaze, angle of view, distance and so forth – our eyes never see the same image twice. Yet our perception of the cat remains stable, an attribute of our visual system known as “invariance.”

“This invariance is fundamental to our ability to recognize objects – it feels effortless, but it is a central challenge for computational neuroscience,” explained James DiCarlo, the senior author of the new study. “We want to understand how our brains acquire invariance and how we might incorporate it into computer vision systems.”

In previous work, DiCarlo tested this “temporal contiguity” idea in humans by creating an altered visual world in which the normal rule did not apply. An object would appear in peripheral vision, but as the eyes moved to examine it, the object would be swapped for a different object. Although the subjects did not perceive the change, they soon began to confuse the two objects, consistent with the temporal contiguity hypothesis.

In the new study, DiCarlo had monkeys watch a similarly altered world while recording from neurons in the inferior temporal (IT) cortex – a high-level visual brain area where object invariance is thought to arise. IT neurons “prefer” certain objects and respond to them regardless of where they appear within the visual field.

“We first identified an object that an IT neuron preferred, such as a sailboat, and another, less preferred object, maybe a teacup,” co-researcher Nuo Li explained. “When we presented objects at different locations in the monkey’s peripheral vision, they would naturally move their eyes there. One location was a swap location. If a sailboat appeared there, it suddenly became a teacup by the time the eyes moved there. But a sailboat appearing in other locations remained unchanged.”

After the monkeys spent time in this altered world, their IT neurons became confused, just like the previous human subjects. The sailboat neuron, for example, still preferred sailboats at all locations – except at the swap location, where it learned to prefer teacups. The longer the manipulation, the greater the confusion, exactly as predicted by the temporal contiguity hypothesis.

Importantly, just as human infants can learn to see without adult supervision, the monkeys received no feedback from the researchers. Instead, the changes in their brain occurred spontaneously as the monkeys looked freely around the computer screen. “We were surprised by the strength of this neuronal learning, especially after only one or two hours of exposure,” DiCarlo told the journal Science. “Even in adulthood, it seems that the object-recognition system is constantly being retrained by natural experience. Considering that a person makes about 100 million eye movements per year, this mechanism could be fundamental to how we recognize objects so easily.”

Related:

Context And Computer Vision

Computer Recognizes Attractiveness In Women

Qualia

Comments are closed.