Detecting extraterrestrial life from tell-tale atmospheric signatures is much easier to do when the planet under observation is orbiting a dying star, say Harvard Smithsonian scientists who believe that white dwarf systems are the best candidates for catching our first glimpse of life outside our solar system. Explaining their reasoning in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the astrophysicists suggest that such a discovery could be made in the next decade by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.

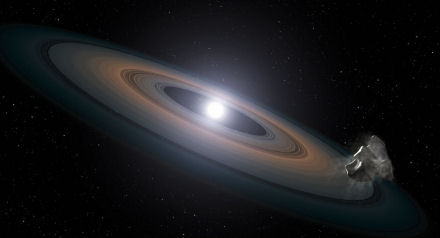

White dwarves – typically about the size of Earth – are stars in their final throes of stellar life. Before a star becomes a white dwarf it swells into a red giant, engulfing and destroying any nearby planets. But the scientists say that a white dwarf cools slowly over billions of years, providing plenty of time for a new planet to form from debris or migrate inward from a more distant orbit.

Any exoplanet that was orbiting a white dwarf would likely be found using a transit search. Transit searches rely on the planet passing in front of the star and blocking some of its light. The scientists, Avi Loeb and Dan Maoz, reason that since a white dwarf is much smaller than other stars, any transiting planet would block a large fraction of its light and create a very obvious signal.

For tell-tale signs of life, astronomers are particularly interested in finding oxygen. On Earth, oxygen is continuously replenished through photosynthesis. Were all life to cease on Earth, our atmosphere would quickly become devoid of oxygen, which would dissolve in the oceans and oxidize the surface. Loeb says that therefore, the presence of large quantities of oxygen in the atmosphere of a distant planet would signal the likely presence of life there.

Detecting what gases a remote planet’s atmosphere is composed of relies on taking spectral measurements of the star’s light as the exoplanet under observation transits across the face of the star. The light from the star – filtered by the exoplanet’s atmosphere – provides a detailed picture of which gases are present in the atmosphere of the exoplanet.

According to Loeb, the very robust transit signal inherent to a white dwarf and any transiting exoplanets would also provide much more accessible spectral data – thus making atmospheric analysis much easier. “Other stars are much larger and brighter than a white dwarf, their glare would overwhelm the faint signal from an orbiting planet’s atmosphere,” he explained.

To support their argument, Loeb and Maoz have created a synthetic spectrum, replicating what the James Webb Space Telescope would see if it examined a habitable planet orbiting a white dwarf. They found that both oxygen and water vapor would be detectable with only a few hours of total observation time. “In the quest for extraterrestrial biological signatures, the first stars we study should be white dwarfs,” Loeb concludes.

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Earth-like planets may be closer than previously thought

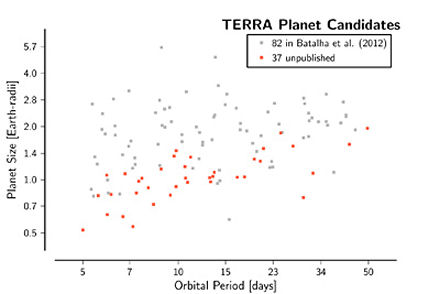

Habitable planets galore, suggests Kepler data-crunching

New evidence for water and organics on Mercury

Earth-sized planet found nearby in Alpha Centauri system

Comments are closed.