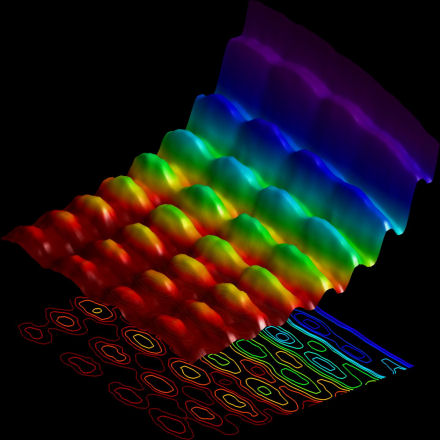

About a hundred years ago, in his theory of general relativity Albert Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves, “ripples” in the fabric of space and time as a result of the universe’s violent and energetic processes, like a collision and merger of black holes or a collapse of supernova.

Gravitational waves are difficult to detect because the origin of these waves are light-years away. While traveling toward the Earth’s direction, the ripples get much smaller in size—much like the ripples you see near the edge of the pond when you throw a rock at the water in the middle. Detecting such small waves has been the challenge in validating Einstein’s predictions.

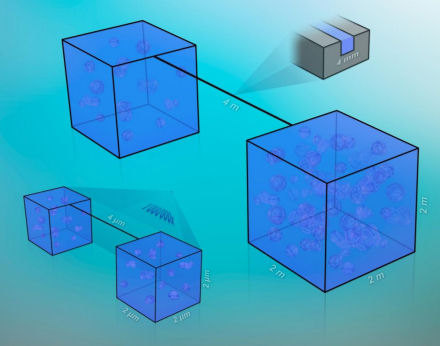

Earlier this year, researchers at LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) announced that they detected the gravitational waves for the first time, proving that Einstein’s prediction was correct and providing support for his theory of general relativity. LIGO researchers had to use an extremely refined technology that would be able to detect the small waves. In fact, when the wave stretched the space by one part in 1021, causing the Earth to expand and contract by 1/100,000 of a nanometer—which is about how wide an atomic nucleus is.

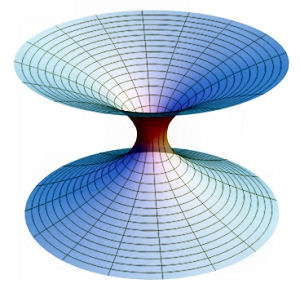

The gravitational waves were a result of a merger of two massive black holes that were 36 and 28 times the mass of the sun.

Last week, researchers announced that they detected the gravitational waves again. The second wave event, named GW151226, was a result of another black hole merger—although this merger was smaller in size, as the black holes were 14 and eight times the mass of the sun.

The data the researcher gathered not only is significant for showing that the technology actually can detect the gravitational waves, but also for studying the behaviors of black holes. Alessandra Buonanno, director at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, said the data from the second black hole merger event matches her team’s predictions that black holes orbits before merging.

“GW151226 perfectly matches our theoretical predictions for how two black holes move around each other for several tens of orbits and ultimately merge,” Buonanno said. “Remarkably, we could also infer that at least one of the two black holes in the binary was spinning.”

The merger that led to GW151226 occurred about 1.4 billion years ago, and the signal that LIGO researchers detected came from the black holes’ last 27 orbits before the merger.

According to Gabriela Gonzalez, professor of physics and astronomy at Louisiana State University, the advancement of wave-detecting technology could also help in figuring out the locations of black holes in our universe. The arrival times of the waves at different LIGO locations (Livingston, LA and Hanford, WA) can help the researchers to determine the position of the wave’s origin.

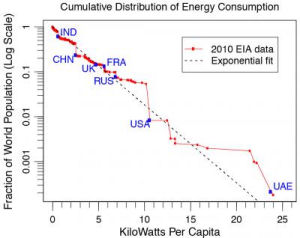

“It is very significant that these black holes were much less massive than those observed in the first detection,” Gonzalez said. “Because of their lighter masses compared to the first detection, they spent more time—about one second—in the sensitive band of the detectors. It is a promising start to mapping the populations of black holes in our universe.”

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Triple star system could reveal true nature of gravity

Entangled quarks hint at reconciliation of quantum mechanics and general relativity

Distant galaxy poses astronomical puzzle

Comments are closed.