Astronomers have suggested that the dark matter halos that envelop entire galaxies may not be completely dark after all, and could contain rogue stars that have been flung out of the galaxy. The case for dark matter not being quite so dark is made by astronomers in the current issue of the journal Nature.

Central to their theory is the conundrum of why we see more light in the universe than we should. When looking at the cosmos, astronomers have seen what are neither stars nor galaxies nor a uniform dark sky, but rather mysterious, sandpaper-like smatterings of light, which UCLA’s Edward L. (Ned) Wright refers to as “fluctuations.”

One explanation is that the fluctuations in the background are from very distant unknown galaxies. A second is that they’re from unknown galaxies that are not so far away – faint galaxies whose light has been traveling to us for only 4-5 billion years (a short time in astronomy terms). In the Nature paper, Wright and his colleagues present evidence that both these explanations are wrong, and they propose an alternative.

The first explanation – that the fluctuations are from very distant galaxies – is nowhere close to being supported by the data, said Wright, a UCLA professor of physics and astronomy. “The idea of not-so-far-away faint galaxies is better, but still not right,” he added. “It’s off by a factor of about 10; the ‘distant galaxies’ hypothesis is off by a factor of about 1,000.”

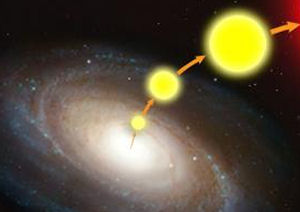

Wright and his colleagues contend that the orphan stars that were kicked to the edges of space during violent collisions and mergers of galaxies may be the cause of the infrared light “halos” across the sky and may explain the mystery of the excess emitted infrared light.

“Galaxies exist in dark matter halos that are much bigger than the galaxies; when galaxies form and merge together, the dark matter halo gets larger and the stars and gas sink to the middle of the halo,” explained Wright. “What we’re saying is one star in a thousand does not do that and instead gets distributed like dark matter. You can’t see the dark matter very well, but we are proposing that it actually has a few stars in it – only one-tenth of 1 percent of the number of stars in the bright part of the galaxy.” He added that in large clusters of galaxies, astronomers have found much higher percentages of intra-halo light, as large as 20 percent.

Future research, especially with the James Webb Space Telescope, should provide further insights, Wright believes. “What we really need to be able to do is to see and identify the galaxies that are producing all the light in the infrared background,” he said. “The history of all the production of light in the universe is encoded in this background. We’re saying the fluctuations can be produced by the fuzzy edges of galaxies that existed at the same time that most of the stars were created, about 10 billion years ago. That could be done to a much greater extent once the James Webb Space Telescope is operational because it will be able to see much more distant, fainter galaxies.”

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

New blow to dark matter theory

Modified Newtonian dynamic could do away with dark matter

Nomad planets seeding life throughout the universe?

![Dark Matter Volume 1: Rebirth [Paperback] Mallozzi, Joseph and Brown, Garry picture](/store/img/g/drsAAOSwjFNlzv~T/s-l225/Dark-Matter-Volume-1-Rebirth-Paperback-Mallozzi-Jo.jpg)

Comments are closed.