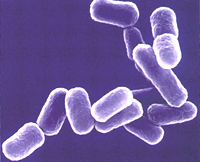

Bacteria can anticipate future events and prepare for them, according to new research that explores how a microorganism’s genetic networks are hard-wired to “foresee” what comes next in a sequence of events.

Reporting their findings in Nature, the Weizmann Institute of Science researchers explained how E. coli bacteria, which normally cruise harmlessly down the digestive tract, encounter a number of different environments on their way. In particular, they find that one type of sugar – lactose – is invariably followed by a second sugar – maltose – soon afterward. Researcher Yitzhak Pilpel and his team in the Molecular Genetics Department checked the bacteria’s genetic response to lactose and found that, in addition to the genes that enable it to digest lactose, the gene network for utilizing maltose was partially activated. When they switched the order of the sugars, giving the bacteria maltose first, there was no corresponding activation of lactose genes, implying that bacteria have naturally “learned” to get ready for a serving of maltose after a lactose appetizer.

Pavlov first demonstrated this type of adaptive anticipation, known as a conditioned response, in dogs in the 1890s. He trained the dogs to salivate in response to a stimulus by repeatedly ringing a bell before giving them food. In the microorganisms, says Pilpel, “evolution over many generations replaces conditioned learning, but the end result is similar.”

“In both evolution and learning,” explains researcher Amir Mitchell, “the organism adapts its responses to environmental cues, improving its ability to survive. This is not a generalized stress response, but one that is precisely geared to an anticipated event.”

To see whether the microorganisms were truly exhibiting a conditioned response, Pilpel and Mitchell devised a further test for the E. coli based on another of Pavlov’s experiments. When Pavlov stopped giving the dogs food after ringing the bell, the conditioned response faded until they eventually ceased salivating at its sound. The scientists did something similar, placing bacteria in an environment containing the first sugar, lactose, but not following it up with maltose. After several months, the bacteria had evolved to stop activating their maltose genes at the taste of lactose, only turning them on when maltose was actually available.

“This showed us that there is a cost to advanced preparation, but that the benefits to the organism outweigh the costs in the right circumstances,” says Pilpel. What are those circumstances? Based on the experimental evidence, the research team created a sort of cost/benefit model to predict the types of situations in which an organism could increase its chances of survival by evolving to anticipate future events. The researchers are already planning a number of new tests for their model, as well as different avenues of experimentation based on the insights they have gained.

The researchers believe that genetic conditioned response may be a widespread means of evolutionary adaptation that enhances survival in many organisms – one that may also take place in the cells of higher organisms, including humans. These findings could have practical implications, as well. Genetically engineered microorganisms for fermenting plant materials to produce biofuels, for example, might work more efficiently if they gained the genetic ability to prepare themselves for the next step in the process.

Related:

Microbe Colonies Show Sophisticated Learning Behaviors

Bacterial Behavior Poorly Understood

Adaptive proteins “control” their own evolution

Comments are closed.