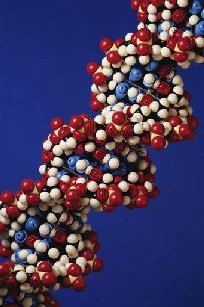

Researchers have traced social behavior traits, such as monogamy, to differences in the length of seemingly non-functional DNA, sometimes referred to as junk DNA. In the study, researchers at the Yerkes Primate Research Center and the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience examined whether the junk DNA associated with the vasopressin receptor gene affected social behavior in male prairie voles, a rodent species. Previous studies have shown the vasopressin receptor gene regulates social behaviors in many species.

The study looked at two groups of prairie voles with short and long versions of the junk DNA, more formally known as microsatellite DNA. By comparing the behavior of male offspring after they matured, they discovered microsatellite length affects gene expression patterns in the brain. Each animal species has its own signature microsatellites; for example, the repeating letter sequences are much longer in monogamous than in polygamous vole species. But even within a species, there are differences in the number of letters in the sequence among individuals.

Prairie voles with the long version have more receptors in circuits for social recognition, so release of vasopressin during social encounters facilitates social behavior. If such familial traits are adaptive in a given environment, they are passed along to future generations through natural selection. “This is the first study to demonstrate a link between microsatellite length, gene expression patterns in the brain and social behavior across several species,” said researcher Larry Young. “Because a significant portion of the human genome consists of junk DNA and due to the way microsatellite DNA expands and contracts over time, microsatellites may represent a previously unknown factor in social diversity.”

The study’s findings extend beyond social diversity in rodents to that in apes and humans. Chimpanzees and bonobos, humans’ closest relatives, have the vasopressin receptor gene, yet only the bonobo, which has been called the most empathetic ape, has a microsatellite similar to that of humans. “That this specific microsatellite is missing from the chimpanzee’s DNA may mean the last common ancestor of humans and apes was socially more like the bonobo and less like the relatively aggressive and dominance-oriented chimpanzee,” said Yerkes primate researcher Frans de Waal.

Variability in vasopressin receptor microsatellite length could help account for differences in normal human personality traits, such as shyness, and perhaps influence disorders of sociability like autism and social anxiety disorders, suggest the researchers. “This research appears to have found one of those hotspots in the genome where small differences can have large functional impact. The researchers found individual differences not in a protein-coding region, but in an area that determines a gene’s expression in the brain. This is an extraordinary example of research linking gene variation to brain receptors to behavior,” said Thomas Insel, a director at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Comments are closed.