Traces of ordinary products-flushed and tossed away from millions of homes, gardens and garages-are likely more harmful to the sexual development and reproduction of fish in the Chesapeake Bay than scientists previously thought. The large, shallow Bay-average depth of less than 30 feet-with hundreds of tributaries, has long been considered by ecologists as a very favorable habitat for fish spawning, hatching and nurseries.

However, scientists of the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute (UMBI) report that the list of compounds in pollution that can disrupt fish sexual hormones has widened considerably. Compounds in many detergents, plastics, pesticides, some medicines, and even thalates that keep vinyl soft in cars disrupted the sexual development of juvenile zebra fish in experiments at UMBI’s Center of Marine Biotechnology (COMB) in Baltimore. All of the environmental pollutants were tested at concentrations that can be found in the Chesapeake Bay system.

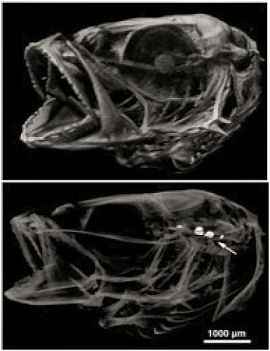

Chemical disruption of a brain gene, which directly affects brain estrogen production, may be a key mechanism for the disruption of the developmental and reproductive capacity of fish. Unlike most animals, many fish produce two forms of a gene responsible for aromatase, an enzyme that makes estrogen–one form in the ovaries, the other in the brain.

First, the researchers discovered that the “differential expression of the brain aromatase gene” was associated with sex differentiation. “It became clear that compounds affecting this gene will thereby affect sex and sexual behavior in fish,” concluded Trant.

A growing number of studies have found that when compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls, dioxins, certain plasticizers, and some detergent additives are in streams or rivers, the fish, birds, frogs and other animals are sometimes all male, or all female, or are partially both sexes in their genitalia. Historically scientists have suspected actualestrogens or chemicals that mimic estrogens in pollution as the causes of the gender-bending effects on fish. Estrogen (or estrogen-like) molecules dock onto a structure called an estrogen receptor in the cells of the liver, ovaries, fat, breast, brain, bone and many other target tissues in humans. The activated receptor initiates a series of changes into action related to sexual physiology. Many of the pollutants, such as PCB’s, some pesticides and petroleum products in the Chesapeake waters are recognized as estrogen molecules by fish and human cells.

“That’s why scientists have focused there,” said Trant. “But, this is worse than we thought before. This is not simply toxicology. It is interfering with the reproduction of the adults, and potentially skewing sex ratios of the populations.”

Comments are closed.