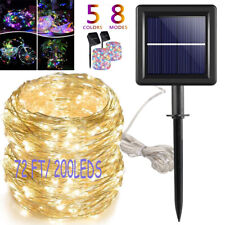

Importantly, the peel-and-stick version from Stanford does not require any direct fabrication on the final carrier substrate. This is a far more dramatic development than it may initially seem. All the challenges associated with putting solar cells on unconventional materials are avoided with the new process, vastly expanding the potential applications of solar technology.

Stanford’s Xiaolin Zheng explained that the new process involves a unique silicon, silicon dioxide and metal “sandwich.” First, a 300-nanometer film of nickel (Ni) is deposited on a silicon/silicon dioxide (Si/SiO2) wafer. Thin-film solar cells are then deposited on the nickel layer utilizing standard fabrication techniques, and covered with a layer of protective polymer. A thermal release tape is then attached to the top of the thin-film solar cells to augment their transfer off of the production wafer and onto a new substrate.

The solar cell is now ready to peel from the wafer. To remove it, the wafer is submerged in water at room temperature and the edge of the thermal release tape is peeled back slightly, allowing water to seep into and penetrate between the nickel and silicon dioxide interface. The solar cell is thus freed from the hard substrate but still attached to the thermal release tape. The research team then heat the tape and solar cell to 90& #176;C for several seconds, then the cell can be applied to virtually any surface using double-sided tape or other adhesive. Finally, the thermal release tape is removed, leaving just the solar cell attached to the chosen surface.

Zheng claims that tests have shown that the peel-and-stick process reliably leaves the thin-film solar cells wholly intact and functional. “There’s also no waste. The silicon wafer is typically undamaged and clean after removal of the solar cells, and can be reused.”

While thin-film solar cells have been fabricated on flexible substrates before, those efforts have required modifications of existing processes or materials. “The main contribution of our work is we have done so without modifying any existing processes, facilities or materials, making them viable commercially. And we have demonstrated our process on a more diverse array of substrates than ever before,” co-researcher Chi Hwan Lee said.

“Now you can put them on helmets, cell phones, convex windows, portable electronic devices, curved roofs, clothing – virtually anything,” added Zheng.

The researchers suggest the process could also be applied to thin-film electronics, including printed circuits and ultra-thin transistors and LCDs. “Obviously, a lot of new products – from ‘smart’ clothing to new aerospace systems – might be possible by combining both thin-film electronics and thin-film solar cells,” observed Zheng. “We may be just at the beginning of this technology.”

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Solar steam generator outshines photovoltaic solar cells

Solar power’s dirty secret: skyrocketing lead pollution

Virus improves solar cell efficiency

Novel solar cells utilize light’s magnetic properties

Comments are closed.