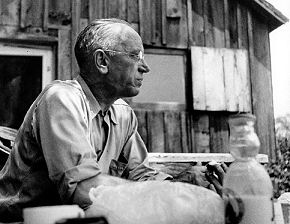

Rising before daylight and perched on a bench at his Sauk County shack in Depression-era Wisconsin, pioneering wildlife ecologist Aldo Leopold (pictured) routinely took notes on the dawn chorus of birds. Beginning with the first pre-dawn calls of the indigo bunting or robin, Leopold would jot down the bird songs he heard, when he heard them, and details such as the light level when they first sang. Lacking a tape recorder, the detailed written record was the best the famous naturalist could do. Now, Stan Temple and co-researcher Christopher Bocast have recreated a soundscape (listen to an MP3 file of the recreation) from Leopold’s 70 year-old notes.

But the recreated dawn chorus that Leopold heard no longer exists at the shack, Temple explains. The mix of species today is different due to changes in the landscape and changes in the bird community.

More noticeable is the thrum of the nearby interstate highway, audible at every hour from Leopold’s storied sanctuary, and the other constant and varied noises of the human animal. “The difference between 1940 and 2012 is overwhelmingly the anthrophony – human-generated noise,” explains Temple. “That’s the big change. In Leopold’s day there was much less of that.”

The soundscape produced by Temple and Bocast is a compressed version of the chorus described by Leopold, using 30 minutes of his notes and compressing them into five minutes of recording. Bird songs and calls were obtained from the extensive collection housed at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library.

The background sound on which they superimposed the bird songs is Wisconsin countryside, but Temple and Bocast struggled to find a place where human noise was as it would have been in Leopold’s time. Temple points out that in the lower 48 states, there is no place more than 35 kilometers from the nearest road, making it nearly impossible to tune out the hum of human activity.

“It is increasingly difficult to study natural soundscapes that represent normality,” says Temple, noting that its not just mechanical human noise that’s encroaching. The rain forests of Hawaii, for example, no longer sound like the rain forests of Hawaii. “They sound more like the rain forests of Puerto Rico because the calls of an introduced, invasive tree frog are becoming pervasive.”

Temple and Bocast, both from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, contend that a sense of land health can be gained by listening to the soundscape. “If sounds are missing and things are there that shouldn’t be, it often indicates underlying ecological problems,” Temple said.

Science, concludes Temple, is only now coming to grips with how nature’s “music” is changing and how much impact the sounds introduced by people have. “We have much to learn about what the noise people make does to the environment,” he notes.

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Hazardous levels of noise exposure for 90% of city dwellers

Pop music created using natural selection and crowdsourcing

Human Noise Wrecks Whales’ Sex Lives

Comments are closed.