The latest American Journal of Human Biology contains details of two studies that contend that poor nutrition and stress – stemming back to the days of slavery – could help explain black-white differences in cardiovascular health in the United States.

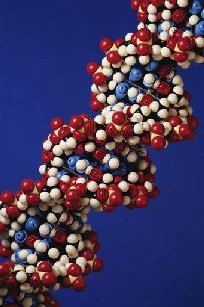

In one study, researchers from Northwestern University explain how nutrients and hormones present in the womb can profoundly shape a fetus’s development, in part by silencing certain genes. These influences, say the research team, can persist into later life to impact adult health, a process known as “fetal programming.” The researchers argue that such intergenerational impacts of environmental factors could help explain racial health differences.

In a related editorial in the journal, Peter Ellison explains that some of the most persistent health disparities in the United States occur between African Americans and European Americans. The causes of those disparities are many and their roots are deep. They are entwined with the history of slavery and discrimination, with rural and inner city neglect, with differential wealth and differential access to health care, with cultural traditions and cultural biases, according to Ellison.

The second study examines why the average birth weight among African-American babies is approximately 250 grams lower than the average birth weight of whites – a difference of 10 percent. According to Grazyna Jasienska, co-author of the study, this may also be the result of conditions experienced by their ancestors during the period of slavery passed through epigenetic, rather than genetic, mechanisms.

Interestingly, prior studies have shown that contemporary black women who were born in African countries ancestral to slave populations, but who live in the U.S., give birth to children with significantly higher weight than black women in the U.S. who have slave ancestry. “Slaves experienced poor nutrition during all stages of life, suffered from a heavy burden of infectious diseases and, in addition, experienced high energetic costs of hard physical labor,” says Jasienska. “Even a short-term nutritional deprivation of pregnant women, when very severe, has been shown to have an intergenerational effect.”

The fetal programming concept suggests that physiology and metabolism, including growth and fat accumulation of the developing fetus, and, thus its birth weight, depend on intergenerational signal of environmental quality passed through generations of matrilinear ancestors. A child’s birth weight may be influenced by nutritional conditions of its grandmother and even great-grandmother. The resulting effects can be seen in both childhood and adulthood, and include a higher risk of hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease, contends Jasienska.

Jasienska says that in the U.S. the condition of many slaves did not immediately improve after the abolition of slavery, so the causes are not as far removed in time from contemporary African Americans as it may seem. Census data from the year 1900 showed that African Americans continued to suffer higher mortality than whites from all major diseases except cancer. Even though several generations have passed since then, it may not have been enough time to eliminate the negative impact of slavery on the health of the contemporary African-American population.

Related:

Skin Deep

Genetically Speaking, Race Doesn’t Exist In Humans

Subliminal Experiments Uncover Deep-Seated Racism

Zeroing-In On Epigenetic Inheritance Mechanism

Comments are closed.