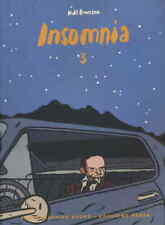

Not being able to get a good night’s sleep is torment enough without being told that insomnia can both cause and prolong clinical depression. There’s no good news to be had in two new studies that show insomnia, far from being a symptom or side effect of depression, may instead precede it, making some patients more likely to become and remain mentally ill. The papers will be published in the Journal of Behavioral Sleep Medicine.

For some time researchers have thought that insomnia and depression were linked, but struggled to establish what the relationship was. The consensus among experts was, until recently, that depression caused insomnia. But along with new drugs designed to treat depression, came the realization that improving depression did not alleviate insomnia. Going against conventional wisdom, the idea that insomnia could be a contributor to, or predictor of, depression gained credence.

What many might find most alarming about the two studies is that those people most at risk of first-time depression are patients with severe “middle insomnia,” where patients wake up frequently during the night, but eventually fall back to sleep each time. This description of inadequate sleep patterns probably account for nearly everyone at some stage of their lives. Michael Perlis, director of the University of Rochester Sleep Research Laboratory, said that: “The new findings are especially significant because they suggest that targeted treatment for insomnia will increase the likelihood and speed of recovery from depression.” Now that the connection between insomnia and depression has finally been made, subsequent trials and studies are being conducted into improving sleep patterns.

Comments are closed.