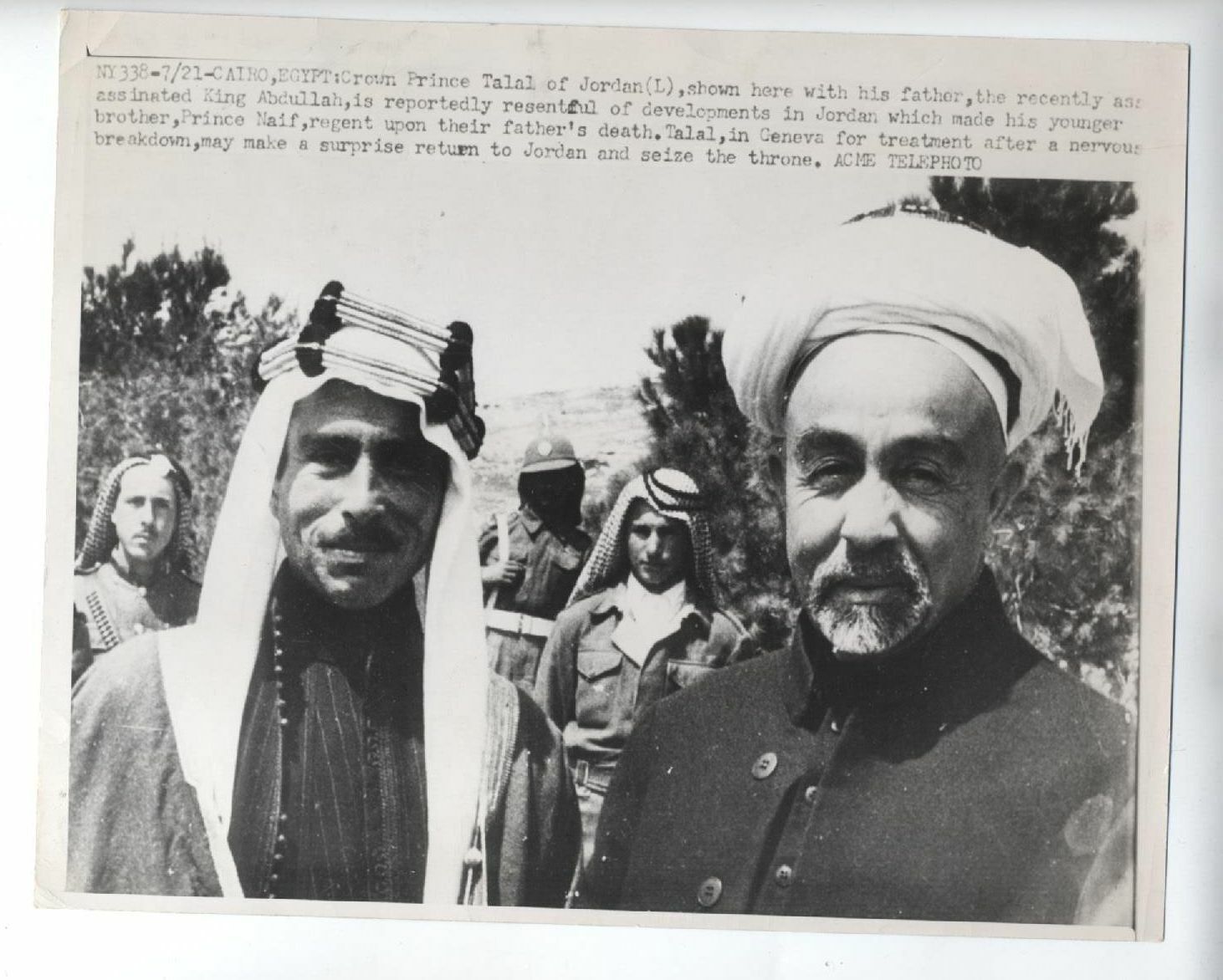

1951 KING ABDULLAH & TALAL JORDAN PHOTO عبد الله الأول بن الحسين VINTAGE For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1951 KING ABDULLAH & TALAL JORDAN PHOTO عبد الله الأول بن الحسين VINTAGE:

$150.00

A vintage photo from 1951 measuring 7 1/8 X 9 inches ofAbdullah I bin Al-Husseinعبد الله الأول بن الحسين & PRINCE TALAL OF JORDAN.Abd Allāh Al-Awal ibn Al-Husayn, February 1882 – 20 July 1951 reigned as Emir of Transjordan from 21 April 1921, and as King of Jordan from 25 May 1946, until his assassination. According to Abdullah, he was a 38th-generation direct descendant of Muhammad as he belongs to the Hashemite family.Born in Mecca, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire, Abdullah was the second of three sons of Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca and his first wife Abdiyya bint Abdullah. He was educated in Istanbul and Hejaz. From 1909 to 1914, Abdullah sat in the Ottoman legislature, as deputy for Mecca, but allied with Britain during World War I. Between 1916 and 1918, he played a key role as architect and planner of the Great Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule that was led by his father Sharif Hussein. Abdullah personally lead guerrilla raids on garrisons.[3]

Abdullah became emir to the Emirate of Transjordan in April 1921, which he established by his own initiative, and became king to its successor state, Jordan, after it gained its independence in 1948. Abdullah ruled until 1951 when he was assassinated in Jerusalem while attending Friday prayers at the entrance of the Al-Aqsa mosque by a Palestinian who feared that the King was going to make peace with Israel.[4] He was succeeded by his son Talal.

Talal bin Abdullah (Arabic: طلال بن عبد الله, Ṭalāl ibn ʿAbdullāh; 26 February 1909 – 7 July 1972) was King of Jordan from the assassination of his father, King Abdullah I, on 20 July 1951, until he was forced to abdicate on 11 August 1952. According to Talal, he was a 39th-generation direct descendant of Muhammad as he belongs to the Hashemite family—who have ruled Jordan since 1921.

Talal was born in Mecca as the eldest child of Abdullah and his wife Musbah bint Nasser. Abdullah was son of Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, who led the Great Arab Revolt during World War I against the Ottoman Empire in 1916. After removing Ottoman rule, Abdullah established the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921, which became a British Protectorate, and ruled as its Emir. During Abdullah's absence, Talal spent his early years alone with his mother. Talal received private education in Amman, later joining Transjordan's Arab Legion as second lieutenant in 1927. He then became aide to his grandfather Sharif Hussein, the ousted King of the Hejaz, during his exile in Cyprus. By 1948, Talal became a general in the Arab Legion.

Abdullah sought independence in 1946, and the Emirate became the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Talal became Crown Prince upon his father's designation as King of Jordan. Abdullah was assassinated in Jerusalem in 1951, and Talal became King. Talal's most revered achievement as King is the establishment of Jordan's modern constitution in 1952, rendering his kingdom as a constitutional monarchy. He ruled for less than thirteen months until he was forced to abdicate by Parliament due to mental illness—reported as schizophrenia. Talal spent the rest of his life at a sanatorium in Istanbul and died there on 7 July 1972. He was succeeded by his oldest son Hussein.[1]Contents1 Early life2 Reign3 Forced abdication and death4 Legacy5 Personal life5.1 Ancestry6 Titles and honours6.1 Titles6.2 Honours7 See also8 References9 BibliographyEarly lifeHe was born in Mecca as the eldest child of Abdullah, an Arab deputy of Mecca in the Ottoman Parliament, and his wife Musbah bint Nasser. Abdullah was the son of Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Sharif Hussein and his sons led the Great Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire in 1916; after removing Ottoman rule, the Sharif's sons established Arab monarchies in place. Abdullah established the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921, a British Protectorate, for which he was Emir. During Abdullah's absence, Talal spent his early years alone with his mother. Talal received private education in Amman, later joining Transjordan's Arab Legion as second lieutenant in 1927. He then became aide to his grandfather Sharif Hussein, the ousted King of the Hejaz, during his exile in Cyprus. By 1948, Talal became a general in the Army.[2]

He was educated privately before attending the British Army's Royal Military College, Sandhurst, from which he graduated in 1929 when he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Cavalry Regiment of the Arab Legion. His regiment was attached to a British regiment in Jerusalem and also to the Royal Artillery in Baghdad.[3]

ReignSee also: Abdullah_I_of_Jordan § Succession_disputes

Talal, when he was Crown Prince of Jordan, 1 May 1948Talal ascended the Jordanian throne after the assassination of his father, Abdullah I, in Jerusalem. His son Hussein, who was accompanying his grandfather at Friday prayers, was also a near victim. On 20 July 1951, Prince Hussein travelled to Jerusalem to perform Friday prayers at the Al-Aqsa Mosque with his grandfather, King Abdullah I. An assassin, fearing that the king might normalise relations with the State of Israel, killed Abdullah, but the 15-year-old Hussein survived.[4]

During his short reign he was responsible for the formation of a liberalised constitution for the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, which made the government collectively, and the ministers individually, responsible before the Jordanian Parliament. The constitution was ratified on 1 January 1952. King Talal is also judged as having done much to smooth the previously strained relations between Jordan and the neighbouring Arab states of Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Talal has been described by his cousin Prince Ra'ad bin Zeid in a 2002 interview as having "very anti-British sentiments", caused by the British's failure to fully comply with the agreement with his grandfather Sharif Hussein ibn Ali in the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence to establish an independent Arab kingdom under his rule.[5] Talal was described by British resident in Transjordan Sir Alec Kirkbride in a 1939 correspondence as being "at heart, deeply anti-British".[6][7] However, Kirkbride doubted the meaningfulness of this animosity towards the British, owing it purely to the "tension" between Talal and his father Emir Abdullah and Talal's desire to create of himself as a "big nuisance as possible".[8]

Israeli historian Avi Shlaim, however, argues that Talal's contempt for the British was genuine as he "bitterly resented British affairs in the affairs of his country" and that such hostility towards the British was downplayed by Kirkbride due to Britain's "self-serving" interests to "protect her reputation".[9] Furthermore, at the time of the succession crisis that occurred after Emir Abdullah I's assassination, Talal was described by contemporary Egyptian and Syrian press as a "great patriotic anti- imperialist" in contrast to his half-brother Naif, who also sought the throne, and was denounced as "weak- minded and entirely subservient to British influence".[10]

Forced abdication and deathA year into Talal's reign, Arab Legion intelligence officer Major Hutson reported that "Amman was seething with a rumor to the effect that the Legion, or Cabinet, intend on handing over West Jordan to Israel and that Talal was deported by the British for refusing to agree".[11] At this time, Talal was reported by British resident Furlonge, Queen Zein (mother of Talal's son and successor Hussein), and Prime Minister Tawfik Abu Al-Huda as suffering from mental illness. Furlonge particularly suggested that Talal be "forced out of Amman" and "forced into a French clinic". Talal was subsequently flown in a civil (not royal) RAF plane to Paris to provide him "treatment".[12]

Talal's reportedly unwell medical condition is highlighted by an incident on May 29, 1952 when Queen Zein (described by British historian Nigel J. Ashton as a "a sophisticated political operator with her own private communication channels with the British"[13]) sought refuge in the British embassy in Paris, claiming that Talal "threatened her with a knife and attempted to kill one of his younger children".[14] Prime Minister Tawfik Abu al-Huda consequently attempted to induce Talal into abdicating, however he was harshly reproached by Talal who said he "had no intentions of abdicating". Furthermore, PM Abu al-Huda received reports that Talal was attempting to challenge the government with the help of "private individuals" and an "officer in the Arab Legion".[15]

This led Abu al-Huda into summoning both houses of parliament to an "extraordinary session", requesting their approval of a motion dictating that Talal be deposed for "medical reasons", specifically "schizophrenia". Abu al-Huda backed up his requests with medical reports and argued that Talal's medical condition was irrevocable, and Talal's deposition was unanimously accepted by parliament later that day.[16]

Nationalist officers in the Army suspected that the parliamentary session to discuss Talal's abdication was a plot against him. They asked the King's aide-de-camp, 'Abd Al'Aziz Asfur, to arrange a meeting with him to arrange a response to the supposed plot. However, Asfur returned to the officers and confirmed the claims about his mental condition.[17]

Abu al-Huda proceeded to rule Jordan, from the day of Talal's deposition on August 11, 1952 until Talal's son Hussein came of age on May 2, 1953, in a "dictatorial" fashion. He was described by Glubb Pasha as a "Prime Minister dictator" who had had ruled "stably" as Emir Abdullah I had done. Glubb Pasha particularly commended this as he noted that Arab countries were presently "unfit for full democracy on the British model".[18] Abu al-Huda's ascension was supported by Political Resident Furlonge as Abu al-Huda was from the "old guard" and thus "accustomed to the existing system and relationship with Britain".[19]

Contrary to his wishes of living in Saudi-ruled Hijaz post-abdication[20], Talal was sent to live the latter part of his life at a sanatorium in Istanbul and died there on 7 July 1972. Talal was buried in the Royal Mausoleum at the Raghadan Palace in Amman.[21]

LegacyDespite his short reign, he is revered for having established a modern constitution of Jordan.[22]

Personal life

From left to right: prince Hassan, king Hussein, princess Basma and prince MuhammadIn 1934, Talal married his first cousin Zein al-Sharaf Talal who bore him four sons and two daughters:

King Hussein (14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999).Princess Asma, died at birth in 1937.Prince Muhammad (born 2 October 1940).Prince Hassan (born 20 March 1947).Prince Muhsin, deceased.Princess Basma (born 11 May and honoursTitlesStyles ofKing Talal of JordanCoat of arms of Jordan.svgReference style His MajestySpoken style Your MajestyAlternative style Sir26 February 1909 – 25 May 1946: His Royal Highness Prince Talal of Jordan25 May 1946 – 20 July 1951: His Royal Highness The Crown Prince of Jordan20 July 1951 – 11 August 1952: His Majesty The King of the Hashemite Kingdom of JordanHonoursJordan:Honorary Lieutenant in the Transjordan Frontier Force(1932)[3]Honorary Major General in the Arab Legion (1949)[3]Field Marshal in the Arab Legion (1951)[3]Grand Collar of the Order of the Hashemites (1951)[3]Grand Master of the Order of al-Hussein bin Ali (1951)[3]Grand Master of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance (1951)[3]Grand Master of the Order of Independence (1951)[3]Iraq:1st Class Order of the Two Rivers of the Kingdom of Iraq (1951)[3]Spain:Grand Cross of the Order of Military Merit (1952)[25]King Abdullah of Jordan was assassinated at the entrance to the El Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem. His assailant, who was shot dead by the bodyguard, was an Arab who had been a member of a military force associated with the ex-Mufti of Jerusalem.Assassin a follower of the ex-Mufti

King Abdullah of Jordan was assassinated by an Arab yesterday at the entrance to the El Aqsa Mosque, in the Old City of Jerusalem. The assassin, who had hidden behind the main gate of the mosque, shot at close range and was himself immediately shot dead by the King's bodyguard.

The King, who was 69, died instantly. His elder son, the Emir Talal, is undergoing medical treatment abroad, and in his absence the younger son, Prince Naif, took the oath of allegiance as Regent at a meeting of the Council of Ministers. The King's body was flown to the capital, Amman, and will be buried in the Royal Cemetery on Monday. A state of emergency has been proclaimed throughout the country.

The assassin is reported to have been identified as Mustafa Shukri Ashshu, a 21-year-old tailor in the Old City. During the Arab-Jewish war he was a member of the "dynamite squad" attached to the Arab irregular forces which were associated with the ex-Mufti of Jerusalem and became bitter enemies of Abdullah. Information was received at the Jordan Legation in London last night that several men were concerned in the crime.

Search for accomplices

Jordan guards stopped all traffic between the Jordan and Israel sectors of Jerusalem and closed the frontier at noon, fifteen minutes after the assassination. A search was made in the Old City for accomplices. The Aqsa Mosque, where the King was murdered as he was about to attend noon prayers, is within half a mile of the Israeli border.

Azzam Pasha, Secretary-General of the Arab League, said in Alexandria yesterday that he was going to Amman immediately to express the regret of the Arab world. "King Abdullah served the Arab States all his life and the assassination is a crime condemned by every religion." The Regent of Iraq and the Jordan Minister in London will fly to Amman to-day.

Messages of condolence have been sent from the Middle Eastern capitals to the Jordan Royal Family. At the United Nations headquarters in New York, Dr. Ralph Bunche, the former Acting Mediator in Palestine, said: "King Abdullah was a unique personality in the modern world. He was a philosopher and poet, but he was also a realist and politically very astute. He was one of the most c harming men I have ever known. In all my dealings with him in connection with the Palestine dispute, I found him always friendly and reasonable and one whose word could be fully trusted."

General William Riley, Chief of Staff of the United Nations Truce Commission in Palestine, said: "I regret exceedingly the loss of a very fine individual with whom I have been associated with both personally and officially, on matters pertaining the Palestine problems over the past three years. I have lost a good friend."

A French Foreign Office spokesman said the assassination was seen as an alarming sign of increasing tension and instability in the Middle East. This was more especially so as it followed the killing of Riad Bey es Sohl, the former Premier of the Lebanon, who was assassinated at Amman four days ago.

Four assassinations

King Abdullah is the fourth Moslem leader to be assassinated in four months. General Razmara, the Persian Prime Minister, like King Abdullah, was shot while entering a mosque by a member of the Fidiyan Islam sect on March 7. Twelve days later his close friend Dr Abdul Hamid Zanganeh, a Minister of Education, was shot on the steps of Tehran University, also by a member of Fidiyan Islam.

The third murder was that of Riad es Sohl, in Jordan. He had visited King Abdullah and was on his way to the airport to return to Beirut. His murderers were said to be members of the Syrian Nationalist party.

The Crown Prince Talal, who is 40, is now undergoing medical treatment following a "general health deterioration which has produced nerve weakness." Prince Naif, the new Regent, went to Sandhurst after spending some time in the desert with a nomad tribe. Prince Talal's son, the 14-year-old Prince Hussein, is now studying at Victoria College, Alexandria.

The young King Feisal of Iraq, who is now at school in Britain, is Abdullah's great-nephew. Abdullah's father, King Hussein, was deposed as ruler of the Hejaz by King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia, beginning a feud between the two families which ended after 25 years when Abdullah paid a state visit to Saudi Arabia in 1948.

Abdullah's part in stabilising Middle East

The news of the assassination of King Abdullah of Jordan has been received with profound distress and horror in London. A message of sympathy has been sent by the King to the family of King Abdullah.

The kingdom of Jordan was one of the stabilising elements in the Middle East. For this Abdullah was himself primarily responsible. He leaves behind him, however, a strong Government headed by an energetic and competent Prime Minister. It may be hoped, therefore, that the immediate effects on law and order in Jordan may not prove as disastrous as they would probably be in other Arab countries.

The assassin is stated to be an Arab tailor, formerly a member of forces associated with the ex-Mufti of Jerusalem. This might give some indication of the purpose which lay behind the act. The ex-Mufti, who spent part of the war in Berlin giving such assistance as he could to the Germans, has long been a bitter political enemy of King Abdullah. After Britain surrendered the mandate over Palestine the ex-Mufti put himself at the head of a movement to create an Arab State in Palestine.

In 1950, after the fighting between the Arab States and Israel had been brought to an end, King Abdullah formally incorporated within his kingdom that part of Palestine which bordered on Jordan and which was still occupied by his troops. This step was subsequently recognised by the British and American Governments. It naturally provoked the bitter enmity of the ex-Mufti, whose movement for an Arab Palestine State has steadily been losing support ever since. No information has, however, yet reached London connecting the assassination of King Abdullah directly with the ex-Mufti's movement. The ex-Mufti is believed to be in Syria at present.

Mr Churchill said to-day, after learning of the assassination: "I deeply regret the murder of this wise and faithful Arab ruler, who never deserted the cause of Britain and held out the hand of reconciliation to Israel." The Israeli Minister in London commented: "The assassination of King Abdullah has not only deprived the people of Jordan of their monarch but constitutes a serious blow to peace and stability in the Middle East. King Abdullah was a man who worked hard for understanding and peace between Israel and Jordan and whose efforts, if successful, would have contributed much to the welfare and progress of the entire area."

RITTEN BY: The Editors of Encyclopaedia BritannicaSee Article HistoryAlternative Title: ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-ḤusaynʿAbdullāh I, in full ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Ḥusayn, (born 1882, Mecca—died July 20, 1951, Jerusalem), statesman who became the first ruler (1946–51) of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

ʿAbdullāh, the second son of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, the ruler of the Hejaz, was educated in Istanbul in what was then the Ottoman Empire. After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, he represented Mecca in the Ottoman parliament. Early in 1914 he joined the Arab nationalist movement, which sought independence for Arab territories in the Ottoman Empire. In 1915–16 he played a leading role in clandestine negotiations between the British in Egypt and his father that led to the proclamation (June 10, 1916) of the Arab revolt against the Ottomans.

ʿAbdullāh, the first king of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.ʿAbdullāh, the first king of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.King ʿAbdullāh I of Jordan (left) with his younger son, Nāʾif.King ʿAbdullāh I of Jordan (left) with his younger son, Nāʾif.Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.On March 8, 1920, the Iraqi Congress, an organization of questionable legitimacy, proclaimed ʿAbdullāh constitutional king of Iraq. But he declined the Iraqi throne, which was given to his brother Fayṣal I, whom French troops had driven out of Damascus a year earlier (July 1920). Upon Fayṣal’s ascent to the throne, ʿAbdullāh occupied Transjordan and threatened to attack Syria. He gradually negotiated the legal separation of Transjordan from Britain’s Palestine mandate.

ʿAbdullāh aspired to create a united Arab kingdom encompassing Syria, Iraq, and Transjordan. During World War II (1939–45), he actively sided with the United Kingdom, and his army, the Arab Legion—the most effective military force in the Arab world—took part in the British occupation of Syria and Iraq in 1941. In 1946 Transjordan became independent, and ʿAbdullāh was crowned in Amman on May 25, 1946. He was the only Arab ruler prepared to accept the United Nations’ partitioning of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states (1947). In the war with Israel in May 1948, his armies occupied the region of Palestine due west of the Jordan River, which came to be called the West Bank, and captured east Jerusalem, including much of the Old City. Two years later he annexed the West Bank territory into the kingdom—thereupon changing the name of the country to Jordan. That annexation angered his former Arab allies, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, all of which wanted to see the creation of a Palestinian Arab state on the West Bank. ʿAbdullāh’s popularity at home declined, and he was assassinated by a Palestinian nationalist. The reign of his son Ṭalāl, who suffered from severe mental illness, was brief. A second son, Nāʾif, was passed over, and the throne soon went to Ṭalāl’s son Ḥussein.

Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein (Arabic: عبد الله الأول بن الحسين, Abd Allāh Al-Awal ibn Al-Husayn, February 1882 – 20 July 1951) reigned as Emir of Transjordan from 21 April 1921, and as King of Jordan from 25 May 1946, until his assassination. According to Abdullah, he was a 38th-generation direct descendant of Muhammad as he belongs to the Hashemite family.

Born in Mecca, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire, Abdullah was the second of three sons of Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca and his first wife Abdiyya bint Abdullah. He was educated in Istanbul and Hejaz. From 1909 to 1914, Abdullah sat in the Ottoman legislature, as deputy for Mecca, but allied with Britain during World War I. Between 1916 and 1918, he played a key role as architect and planner of the Great Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule that was led by his father Sharif Hussein. Abdullah personally lead guerrilla raids on garrisons.[3]

Abdullah became emir to the Emirate of Transjordan in April 1921, which he established by his own initiative, and became king to its successor state, Jordan, after it gained its independence in 1948. Abdullah ruled until 1951 when he was assassinated in Jerusalem while attending Friday prayers at the entrance of the Al-Aqsa mosque by a Palestinian who feared that the King was going to make peace with Israel.[4] He was succeeded by his son Talal.Contents1 Early political career2 Founding of the Emirate of Transjordan3 Expansionist aspirations4 Assassination5 Marriages and children6 Ancestry7 Titles and honours8 Gallery9 Notes10 References11 External linksEarly political careerIn their Revolt and their Awakening, Arabs never incited sedition or acted out of greed, but called for justice, liberty and national sovereignty.Abdullah's about the Great Arab Revolt [5]In 1910, Abdullah persuaded his father to stand, successfully, for Grand Sharif of Mecca, a post for which Hussein acquired British support. In the following year, he became deputy for Mecca in the parliament established by the Young Turks, acting as an intermediary between his father and the Ottoman government.[6] In 1914, Abdullah paid a clandestine visit to Cairo to meet Lord Kitchener to seek British support for his father's ambitions in Arabia.[7]

Abdullah maintained contact with the British throughout the First World War and in 1915 encouraged his father to enter into correspondence with Sir Henry McMahon, British high commissioner in Egypt, about Arab independence from Turkish rule. (see McMahon-Hussein Correspondence).[6] This correspondence in turn led to the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans.[1] During the Arab Revolt of 1916–18, Abdullah commanded the Arab Eastern Army.[7] Abdullah began his role in the Revolt by attacking the Ottoman garrison at Ta'if on 10 June 1916.[8] The garrison consisted of 3,000 men with ten 75-mm Krupp guns. Abdullah led a force of 5,000 tribesmen but they did not have the weapons or discipline for a full attack. Instead, he laid siege to town. In July, he received reinforcements from Egypt in the form of howitzer batteries manned by Egyptian personnel. He then joined the siege of Medina commanding a force of 4,000 men based to the east and north-east of the town.[9] In early 1917, Abdullah ambushed an Ottoman convoy in the desert, and captured £20,000 worth of gold coins that were intended to bribe the Bedouin into loyalty to the Sultan.[10] In August 1917, Abdullah worked closely with the French Captain Muhammand Ould Ali Raho in sabotaging the Hejaz Railway.[11] Abdullah's relations with the British Captain T. E. Lawrence were not good, and as a result, Lawrence spent most of his time in the Hejaz serving with Abdullah's brother, Faisal, who commanded the Arab Northern Army.[7]

Founding of the Emirate of Transjordan

Abdullah I of Transjordan during the visit to Turkey with Turkish President Mustafa KemalWhen French forces captured Damascus at the Battle of Maysalun and expelled his brother Faisal, Abdullah moved his forces from Hejaz into Transjordan with a view to liberating Damascus, where his brother had been proclaimed King in 1918.[6] Having heard of Abdullah's plans, Winston Churchill invited Abdullah to a famous "tea party" where he convinced Abdullah to stay put and not attack Britain's allies, the French. Churchill told Abdullah that French forces were superior to his and that the British did not want any trouble with the French. On 8 March 1920, Abdullah was proclaimed King of Iraq by the Iraqi Congress but he refused the position. After his refusal, his brother who had just been defeated in Syria, accepted the position.[1]

Although Abdullah established a legislative council in 1928, its role remained advisory, leaving him to rule as an autocrat.[6] Prime Ministers under Abdullah formed 18 governments during the 23 years of the Emirate.

Abdullah set about the task of building Transjordan with the help of a reserve force headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Peake, who was seconded from the Palestine police in 1921.[6] The force, renamed the Arab Legion in 1923, was led by John Bagot Glubb between 1930 and 1956.[6] During World War II, Abdullah was a faithful British ally, maintaining strict order within Transjordan, and helping to suppress a pro-Axis uprising in Iraq.[6] The Arab Legion assisted in the occupation of Iraq and Syria.[1]

Abdullah negotiated with Britain to gain independence. On 25 May 1946, the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (renamed the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan on 26 April 1949) was proclaimed independent and Abdullah crowned king in Amman.[1]

Expansionist aspirations

King Abdullah declaring the end of the British Mandate and the independence of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 25 May 1946.Abdullah, alone among the Arab leaders of his generation, was considered a moderate by the West.[citation needed] It is possible that he might have been willing to sign a separate peace agreement with Israel, but for the Arab League's militant opposition. Because of his dream for a Greater Syria within the borders of what was then Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon, and the British Mandate for Palestine under a Hashemite dynasty with "a throne in Damascus," many Arab countries distrusted Abdullah and saw him as both "a threat to the independence of their countries and they also suspected him of being in cahoots with the enemy" and in return, Abdullah distrusted the leaders of other Arab countries.[12][13][14]

Abdullah supported the Peel Commission in 1937, which proposed that Palestine be split up into a small Jewish state (20 percent of the British Mandate for Palestine) and the remaining land be annexed into Transjordan. The Arabs within Palestine and the surrounding Arab countries objected to the Peel Commission while the Jews accepted it reluctantly.[15] Ultimately, the Peel Commission was not adopted. In 1947, when the UN supported partition of Palestine into one Jewish and one Arab state, Abdullah was the only Arab leader supporting the decision.[1]

In 1946–48, Abdullah actually supported partition in order that the Arab allocated areas of the British Mandate for Palestine could be annexed into Transjordan. Abdullah went so far as to have secret meetings with the Jewish Agency (future Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir was among the delegates to these meetings) that came to a mutually agreed upon partition plan independently of the United Nations in November 1947.[16] On 17 November 1947, in a secret meeting with Meir, Abdullah stated that he wished to annex all of the Arab parts as a minimum, and would prefer to annex all of Palestine.[17][18] This partition plan was supported by British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin who preferred to see Abdullah's territory increased at the expense of the Palestinians rather than risk the creation of a Palestinian state headed by the Mufti of Jerusalem Mohammad Amin al-Husayni.[6][19]

No people on earth have been less "anti-Semitic" than the Arabs. The persecution of the Jews has been confined almost entirely to the Christian nations of the West. Jews, themselves, will admit that never since the Great Dispersion did Jews develop so freely and reach such importance as in Spain when it was an Arab possession. With very minor exceptions, Jews have lived for many centuries in the Middle East, in complete peace and friendliness with their Arab neighbours.Abdullah's essay titled "As the Arabs see the Jews" in The American Magazine, six months before the onset of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War[20]The claim has, however, been strongly disputed by Israeli historian Efraim Karsh. In an article in Middle East Quarterly, he alleged that "extensive quotations from the reports of all three Jewish participants [at the meetings] do not support Shlaim's account...the report of Ezra Danin and Eliahu Sasson on the Golda Meir meeting (the most important Israeli participant and the person who allegedly clinched the deal with Abdullah) is conspicuously missing from Shlaim's book, despite his awareness of its existence".[21] According to Karsh, the meetings in question concerned "an agreement based on the imminent U.N. Partition Resolution, [in Meir's words] "to maintain law and order until the UN could establish a government in that area"; namely, a short-lived law enforcement operation to implement the UN Partition Resolution, not obstruct it".[21]

On 4 May 1948, Abdullah, as a part of the effort to seize as much of Palestine as possible, sent in the Arab Legion to attack the Israeli settlements in the Etzion Bloc.[17] Less than a week before the outbreak of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Abdullah met with Meir for one last time on 11 May 1948.[17] Abdullah told Meir, "Why are you in such a hurry to proclaim your state? Why don't you wait a few years? I will take over the whole country and you will be represented in my parliament. I will treat you very well and there will be no war".[17] Abdullah proposed to Meir the creation "of an autonomous Jewish canton within a Hashemite kingdom," but "Meir countered back that in November, they had agreed on a partition with Jewish statehood."[22] Depressed by the unavoidable war that would come between Jordan and the Yishuv, one Jewish Agency representative wrote, "[Abdullah] will not remain faithful to the 29 November [UN Partition] borders, but [he] will not attempt to conquer all of our state [either]."[23] Abdullah too found the coming war to be unfortunate, in part because he "preferred a Jewish state [as Transjordan's neighbor] to a Palestinian Arab state run by the mufti."[22]King Abdullah welcomed by Palestinian Christian in East Jerusalem on 29 May 1948, the day after his forces took control over the city.The Palestinian Arabs, the neighboring Arab states, and the promise of the expansion of territory and the goal to conquer Jerusalem finally pressured Abdullah into joining them in an "all-Arab military intervention" against the newly created State of Israel on 15 May 1948, which he used to restore his prestige in the Arab world, which had grown suspicious of his relatively good relationship with Western and Jewish leaders.[22][24] Abdullah was especially anxious to take Jerusalem as compensation for the loss of the guardianship of Mecca, which had traditionally been held by the Hashemites until Ibn Saud seized the Hejaz in 1925.[25] Abdullah's role in this war became substantial. He distrusted the leaders of the other Arab nations and thought they had weak military forces; the other Arabs distrusted Abdullah in return.[26][27] He saw himself as the "supreme commander of the Arab forces" and "persuaded the Arab League to appoint him" to this position.[28] His forces under their British commander Glubb Pasha did not approach the area set aside for the new Israel, though they clashed with the Yishuv forces around Jerusalem, intended to be an international zone. According to Abdullah el-Tell it was the King's personal intervention that led to the Arab Legion entering the Old City against Glubb's wishes.

After conquering the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, at the end of the war, King Abdullah tried to suppress any trace of a Palestinian Arab national identity. Abdullah annexed the conquered Palestinian territory and granted the Palestinian Arab residents in Jordan Jordanian citizenship.[1][29] In 1949, Abdullah entered secret peace talks with Israel, including at least five with Moshe Dayan, the Military Governor of West Jerusalem and other senior Israelis.[30] News of the negotiations provoked a strong reaction from other Arab States and Abdullah agreed to discontinue the meetings in return for Arab acceptance of the West Bank's annexation into Jordan.[31]

Assassination

King Abdullah with Glubb Pasha, the day before his assassination, 19 July 1951.On 16 July 1951, Riad Bey Al Solh, a former Prime Minister of Lebanon, had been assassinated in Amman, where rumours were circulating that Lebanon and Jordan were discussing a joint separate peace with Israel.

96 hours later, on 20 July 1951, while visiting Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, Abdullah was shot dead by a Palestinian from the Husseini clan,[24] who had passed through apparently heavy security. Contemporary media reports attributed the assassination to a secret order based in Jerusalem known only as "the Jihad".[32] Abdullah was in Jerusalem to give a eulogy at the funeral and for a prearranged meeting with Reuven Shiloah and Moshe Sasson.[33] He was shot while attending Friday prayers at Al-Aqsa Mosque in the company of his grandson, Prince Hussein. The Palestinian gunman fired three fatal bullets into the King's head and chest. Abdullah's grandson, Prince Hussein, was at his side and was hit too. A medal that had been pinned to Hussein's chest at his grandfather's insistence deflected the bullet and saved his life.[34] Once Hussein became king, the assassination of Abdullah was said to have influenced Hussein not to enter peace talks with Israel in the aftermath of the Six-Day War in order to avoid a similar fate.[35]

The assassin, who was shot dead by the king's bodyguards, was a 21-year-old tailor's apprentice named Mustafa Shukri Ashu.[36][37] According to Alec Kirkbride, the British Resident in Amman, Ashu was a "former terrorist", recruited for the assassination by Zakariyya Ukah, a livestock dealer and butcher.[38]

Ashu was killed; the revolver used to kill the king was found on his body, as well as a talisman with "Kill, thou shalt be safe" written on it in Arabic. The son of a local coffeeshop owner named Abdul Qadir Farhat identified the revolver as belonging to his father. On August 11, the Prime Minister of Jordan announced that ten men would be tried in connection with the assassination. These suspects included Colonel Abdullah at-Tell, who has been Governor of Jerusalem, and several others including Musa Ahmad al-Ayubbi, a Jerusalem vegetable merchant who had fled to Egypt in the days following the assassination. General Abdul Qadir Pasha Al Jundi of the Arab Legion was to preside over the trial, which began on August 18. Ayubbi and at-Tell, who had fled to Egypt, were tried and sentenced in absentia. Three of the suspects, including Musa Abdullah Husseini, were from the prominent Palestinian Husseini family, leading to speculation that the assassins were part of a mandate era opposition group.[39]

The Jordanian prosecutor asserted that Colonel el-Tell, who had been living in Cairo since January 1950, had given instructions that the killer, made to act alone, be slain at once thereafter, to shield the instigators of the crime. Jerusalem sources added that Col. el-Tell had been in close contact with the former Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husayni, and his adherents in the Kingdom of Egypt and in the All-Palestine protectorate in Gaza. El-Tell and Husseini, and three co-conspirators from Jerusalem, were sentenced to death. On 6 September 1951, Musa Ali Husseini, 'Aoffer and Zakariyya Ukah, and Abd-el-Qadir Farhat were executed by hanging.[40]

Abdullah is buried at the Royal Court in Amman.[41] He was succeeded by his son Talal; however, since Talal was mentally ill, Talal's son Prince Hussein became the effective ruler as King Hussein at the age of seventeen. In 1967, el-Tell received a full pardon from King Hussein.

Marriages and childrenAbdullah married three times.[42]

In 1904, Abdullah married his first wife, Musbah bint Nasser (1884 – 15 March 1961), at Stinia Palace, İstinye, Istanbul, Ottoman Empire. She was a daughter of Emir Nasser Pasha and his wife, Dilber Khanum. They had three children:

Princess Haya (1907–1990). Married Abdul-Karim Ja'afar Zeid Dhaoui.King Talal I (26 February 1909 – 7 July 1972).Princess Munira (1915–1987). Never married.In 1913, Abdullah married his second wife, Suzdil Khanum (d. 16 August 1968), at Istanbul, Turkey. They had two children:

Prince Nayef bin Abdullah (14 November 1914 – 12 October 1983; A Colonel of the Royal Jordanian Land Force. Regent for his older half-brother, Talal, from 20 July to 3 September 1951). Married in Cairo or Amman on 7 October 1940 Princess Mihrimah Selcuk Sultan (11 November 1922 – March 2000, Amman, and buried in Istanbul on 2 April 2000), daughter of Prince Şehzade Mehmed Ziyaeddin (1873–1938) and his fifth wife, Neshemend Hanım (1905–1934), and paternal granddaughter of Mehmed V through his first wife.Princess Maqbula (6 February 1921 – 1 January 2001); married Hussein bin Nasser, Prime Minister of Jordan (terms 1963–64, 1967).In 1949, Abdullah married his third wife, Nahda bint Uman, a lady from Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, in Amman. They had one child:

Princess Naifeh (1950–000[when?]); married Samer Ashour.Ancestryvte Hashemites[43][44]

Titles and honours

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)Styles ofKing Abdullah I of Jordanformerly Emir of TransjordanCoat of arms of Jordan.svgReference style His MajestySpoken style Your MajestyAlternative style SirHis Royal Highness Prince Abdullah of Mecca and Hejaz (1882–1921)His Highness the Emir of Transjordan (1921–46)His Majesty the King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (1946–51)

Postage stamp, Transjordan, 1930.Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE), 1920UK OBE 1917 civil BAR.svgGrand Cordon of the Order of the Two Rivers, 1922Ord.2River-ribbon.gifGrand Master of the Order of the Hashemites, 1932Order of the Hashemites (Iraq) - ribbon bar.gifFounding Grand Master of the Order of al-Hussein bin AliJOR Al-Hussein ibn Ali Order BAR.svgGrand Master of the Supreme Order of the RenaissanceJordan004.gifGrand Master of the Order of IndependenceOrder of Independence Jordan.svgOrder of Faisal I, 1st Class, 1932Order of Faisal I (Iraq) - ribbon bar.gifHonorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG), 1935 (KCMG-1927)UK Order St-Michael St-George ribbon.svgKing George V Silver Jubilee Medal, George VI Coronation Medal, 1937GeorgeVICoronationRibbon.pngCollar of the Order of Muhammad Ali of the Kingdom of Egypt, 1948Order of Muhammad Ali (Egipt) - ribbon bar.gifGrand Collar of the Order of Pahlavi of the Empire of Iran, 1949Order of Pahlavi (Iran).gifGrand Cross of the Order of Military Merit (with white distinctive) of Francoist Spain, 6 September 1949[45]ESP Gran Cruz Merito Militar (Distintivo Blanco) pasador.svgGrand Cordon of the Order of Umayyad of Syria, 1950Order Of Ummayad (Syria) - ribbon bar.gif

Abdullah I bin al-Husayn (Arabic: عبد الله الأول بن الحسين, romanized: Abd Allāh al-Awwal bin al-Husayn, 2 February 1882 – 20 July 1951) was the ruler of Jordan from 11 April 1921 until his assassination in 1951. He was Emir of Transjordan, a British protectorate, until 25 May 1946,[1][2] after which he was King of an independent Jordan. He was a member of the Hashemite dynasty.

Born in Mecca, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire, Abdullah was the second of four sons of Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, and his first wife, Abdiyya bint Abdullah. He was educated in Istanbul and Hejaz. From 1909 to 1914, Abdullah sat in the Ottoman legislature, as deputy for Mecca, but allied with Britain during World War I. During World War I, he played a key role in secret negotiations with the United Kingdom that led to the Great Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule that was led by his father Sharif Hussein.[5] Abdullah personally led guerrilla raids on garrisons.[6]

Abdullah became emir of Transjordan in April 1921. He upheld his alliance with the British during World War II, and became king after Transjordan gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1946.[5] In 1949, Jordan annexed the West Bank,[5] which angered Arab countries including Syria, Saudi Arabia and Egypt, which all defended the creation of a Palestinian state.[5] He was assassinated in Jerusalem while attending Friday prayers at the entrance of the Al-Aqsa mosque by a nationalist Palestinian in 1951.[7][5] He was succeeded by his eldest son Talal.Contents1 Early political career2 Founding of the Emirate of Transjordan3 Expansionist aspirations4 Assassination4.1 Succession crisis5 Marriages and children6 Ancestry7 Titles and honours7.1 Titles7.2 Honours7.2.1 National honours7.2.2 Foreign honours8 Gallery9 Notes10 Bibliography11 Further reading12 External linksEarly political careerIn their Revolt and their Awakening, Arabs never incited sedition or acted out of greed, but called for justice, liberty and national sovereignty.

Abdullah about the Great Arab Revolt[8]In 1910, Abdullah persuaded his father to stand, successfully, for Grand Sharif of Mecca, a post for which Hussein acquired British support. In the following year, he became deputy for Mecca in the parliament established by the Young Turks, acting as an intermediary between his father and the Ottoman government.[9] In 1914, Abdullah paid a clandestine visit to Cairo to meet Lord Kitchener to seek British support for his father's ambitions in Arabia.[10]

Abdullah maintained contact with the British throughout the First World War and in 1915 encouraged his father to enter into correspondence with Sir Henry McMahon, British high commissioner in Egypt, about Arab independence from Turkish rule. (see McMahon–Hussein Correspondence).[9] This correspondence in turn led to the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans.[3] During the Arab Revolt of 1916–18, Abdullah commanded the Arab Eastern Army.[10] Abdullah began his role in the Revolt by attacking the Ottoman garrison at Ta'if on 10 June 1916.[11] The garrison consisted of 3,000 men with ten 75-mm Krupp guns. Abdullah led a force of 5,000 tribesmen but they did not have the weapons or discipline for a full attack. Instead, he laid siege to town. In July, he received reinforcements from Egypt in the form of howitzer batteries manned by Egyptian personnel. He then joined the siege of Medina commanding a force of 4,000 men based to the east and north-east of the town.[12] In early 1917, Abdullah ambushed an Ottoman convoy in the desert, and captured £20,000 worth of gold coins that were intended to bribe the Bedouin into loyalty to the Sultan.[13] In August 1917, Abdullah worked closely with the French Captain Muhammand Ould Ali Raho in sabotaging the Hejaz Railway.[14] Abdullah's relations with the British Captain T. E. Lawrence were not good, and as a result, Lawrence spent most of his time in the Hejaz serving with Abdullah's brother, Faisal, who commanded the Arab Northern Army.[10]

Founding of the Emirate of Transjordan

Abdullah arrives in Amman 1920

Abdullah 1920

Abdullah I of Transjordan during the visit to Turkey with Turkish President Mustafa Kemal 1937When French forces captured Damascus (1 October 1918) at the Battle of Maysalun (24 July 1920) and expelled his brother Faisal (27 July–1 August 1920), Abdullah moved his forces from Hejaz into Transjordan with a view to liberating Damascus, where his brother had been proclaimed King in 1918.[9] Having heard of Abdullah's plans, Winston Churchill invited Abdullah to Cairo in 1921 for a famous "tea party", where he convinced Abdullah to stay put and not attack Britain's allies, the French. Churchill told Abdullah that French forces were superior to his and that the British did not want any trouble with the French. On 8 March 1920, Abdullah was proclaimed King of Iraq by the Iraqi Congress but he refused the position. After his refusal, his brother Faisal who had just been defeated in Syria, accepted the position. Abdullah headed to north to Transjordan and established an emirate there[when?][clarification needed] after being welcomed into the country by its inhabitants.[3]

Although Abdullah established a legislative council in 1928, its role remained advisory, leaving him to rule as an autocrat.[9] Prime Ministers under Abdullah formed 18 governments during the 23 years of the Emirate.

Abdullah set about the task of building Transjordan with the help of a reserve force headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Peake, who was seconded from the Palestine police in 1921.[9] The force, renamed the Arab Legion in 1923, was led by John Bagot Glubb between 1930 and 1956.[9] During World War II, Abdullah was a faithful British ally, maintaining strict order within Transjordan, and helping to suppress a pro-Axis uprising in Iraq.[9] The Arab Legion assisted in the occupation of Iraq and Syria.[3]

Abdullah negotiated with Britain to gain independence. On 25 May 1946, the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (renamed the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan on 26 April 1949) was proclaimed independent. On the same day, Abdullah was crowned king in Amman.[3]

Expansionist aspirations

King Abdullah declaring the end of the British Mandate and the independence of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 25 May 1946.Abdullah, alone among the Arab leaders of his generation, was considered a moderate by the West.[citation needed] It is possible that he might have been willing to sign a separate peace agreement with Israel, but for the Arab League's militant opposition. Because of his dream for a Greater Syria within the borders of what was then Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon, and the British Mandate for Palestine under a Hashemite dynasty with "a throne in Damascus," many Arab countries distrusted Abdullah and saw him as both "a threat to the independence of their countries and they also suspected him of being in cahoots with the enemy" and in return, Abdullah distrusted the leaders of other Arab countries.[15][16][17]

Abdullah supported the Peel Commission in 1937, which proposed that Palestine be split up into a small Jewish state (20 percent of the British Mandate for Palestine) and the remaining land be annexed into Transjordan. The Arabs within Palestine and the surrounding Arab countries objected to the Peel Commission while the Jews accepted it reluctantly.[18] Ultimately, the Peel Commission was not adopted. In 1947, when the UN supported partition of Palestine into one Jewish and one Arab state, Abdullah was the only Arab leader supporting the decision.[3]

In 1946–48, Abdullah actually supported partition in order that the Arab allocated areas of the British Mandate for Palestine could be annexed into Transjordan. Abdullah went so far as to have secret meetings with the Jewish Agency (Golda Meyerson, the future Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, was among the delegates to these meetings) that came to a mutually agreed upon partition plan independently of the United Nations in November 1947.[19] On 17 November 1947, in a secret meeting with Meir, Abdullah stated that he wished to annex all of the Arab parts as a minimum, and would prefer to annex all of Palestine.[20][21] This partition plan was supported by British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin who preferred to see Abdullah's territory increased at the expense of the Palestinians rather than risk the creation of a Palestinian state headed by the Mufti of Jerusalem Mohammad Amin al-Husayni.[9][22]

No people on earth have been less "anti-Semitic" than the Arabs. The persecution of the Jews has been confined almost entirely to the Christian nations of the West. Jews, themselves, will admit that never since the Great Dispersion did Jews develop so freely and reach such importance as in Spain when it was an Arab possession. With very minor exceptions, Jews have lived for many centuries in the Middle East, in complete peace and friendliness with their Arab neighbours.

Abdullah's essay titled "As the Arabs see the Jews" in The American Magazine, six months before the onset of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War[23]The claim has, however, been strongly disputed by Israeli historian Efraim Karsh. In an article in Middle East Quarterly, he alleged that "extensive quotations from the reports of all three Jewish participants [at the meetings] do not support Shlaim's account...the report of Ezra Danin and Eliahu Sasson on the Golda Meir meeting (the most important Israeli participant and the person who allegedly clinched the deal with Abdullah) is conspicuously missing from Shlaim's book, despite his awareness of its existence".[24] According to Karsh, the meetings in question concerned "an agreement based on the imminent U.N. Partition Resolution, [in Meir's words] "to maintain law and order until the UN could establish a government in that area"; namely, a short-lived law enforcement operation to implement the UN Partition Resolution, not obstruct it".[24]

Historian Graham Jevon discusses the Shlaim and Karsh interpretations of the critical meeting and accepts that there may not have been a "firm agreement" as posited by Shlaim while claiming it is clear that the parties openly discussed the possibility of a Hashemite-Zionist accommodation and further says it is "indisputable" that the Zionists confirmed that they were willing to accept Abdullah's intention.[25]

On 4 May 1948, Abdullah, as a part of the effort to seize as much of Palestine as possible, sent in the Arab Legion to attack the Israeli settlements in the Etzion Bloc.[20] Less than a week before the outbreak of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Abdullah met with Meir for one last time on 11 May 1948.[20] Abdullah told Meir, "Why are you in such a hurry to proclaim your state? Why don't you wait a few years? I will take over the whole country and you will be represented in my parliament. I will treat you very well and there will be no war".[20] Abdullah proposed to Meir the creation "of an autonomous Jewish canton within a Hashemite kingdom," but "Meir countered back that in November, they had agreed on a partition with Jewish statehood."[26] Depressed by the unavoidable war that would come between Jordan and the Yishuv, one Jewish Agency representative wrote, "[Abdullah] will not remain faithful to the 29 November [UN Partition] borders, but [he] will not attempt to conquer all of our state [either]."[27] Abdullah too found the coming war to be unfortunate, in part because he "preferred a Jewish state [as Transjordan's neighbour] to a Palestinian Arab state run by the mufti."[26]King Abdullah welcomed by Palestinian Christians in East Jerusalem on 29 May 1948, the day after his forces took control over the city.The Palestinian Arabs, the neighbouring Arab states, the promise of the expansion of territory and the goal to conquer Jerusalem finally pressured Abdullah into joining them in an "all-Arab military intervention" on 15 May 1948. He used the military intervention to restore his prestige in the Arab world, which had grown suspicious of his relatively good relationship with Western and Jewish leaders.[26][28] Abdullah was especially anxious to take Jerusalem as compensation for the loss of the guardianship of Mecca, which had traditionally been held by the Hashemites until Ibn Saud seized the Hejaz in 1925.[29] Abdullah's role in this war became substantial. He distrusted the leaders of the other Arab nations and thought they had weak military forces; the other Arabs distrusted Abdullah in return.[30][31] He saw himself as the "supreme commander of the Arab forces" and "persuaded the Arab League to appoint him" to this position.[32] His forces under their British commander Glubb Pasha did not approach the area set aside for the Jewish state, though they clashed with the Yishuv forces around Jerusalem, intended to be an international zone. According to Abdullah el-Tell it was the King's personal intervention that led to the Arab Legion entering the Old City against Glubb's wishes.

After conquering the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, at the end of the war, King Abdullah tried to suppress any trace of a Palestinian Arab national identity.[33] Abdullah annexed the conquered Palestinian territory and granted the Palestinian Arab residents in Jordan Jordanian citizenship.[3][33] In 1949, Abdullah entered secret peace talks with Israel, including at least five with Moshe Dayan, the Military Governor of West Jerusalem and other senior Israelis.[34] News of the negotiations provoked a strong reaction from other Arab States and Abdullah agreed to discontinue the meetings in return for Arab acceptance of the West Bank's annexation into the Dome of the Rock, 1948

King Abdullah, in white, leaving the Al-Aqsa Mosque a few weeks before his assassination, July 1951

King Abdullah with Glubb Pasha, the day before Abdullah's assassination, 19 July 1951On 16 July 1951, Riad Bey Al Solh, a former Prime Minister of Lebanon, had been assassinated in Amman, where rumours were circulating that Lebanon and Jordan were discussing a joint separate peace with Israel.

Coffin of King Abdullah I in Jordan, 29 July 1951.png96 hours later, on 20 July 1951, while visiting Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, Abdullah was shot dead by a Palestinian from the Husseini clan,[28] who had passed through apparently heavy security. Contemporary media reports attributed the assassination to a secret order based in Jerusalem known only as "the Jihad", discussed in the context of the Muslim Brotherhood.[36] Abdullah was in Jerusalem to give a eulogy at the funeral and for a prearranged meeting with Reuven Shiloah and Moshe Sasson.[37] He was shot while attending Friday prayers at Al-Aqsa Mosque in the company of his grandson, Prince Hussein. The Palestinian gunman fired three fatal bullets into the King's head and chest. Abdullah's grandson, Prince Hussein, was at his side and was hit too. A medal that had been pinned to Hussein's chest at his grandfather's insistence deflected the bullet and saved his life.[38] Once Hussein became king, the assassination of Abdullah was said to have influenced Hussein not to enter peace talks with Israel in the aftermath of the Six-Day War in order to avoid a similar fate.[39]

The assassin, who was shot dead by the king's bodyguards, was a 21-year-old tailor's apprentice named Mustafa Shukri Ashu.[40][9] According to Alec Kirkbride, the British Resident in Amman, Ashu was a "former terrorist", recruited for the assassination by Zakariyya Ukah, a livestock dealer and butcher.[41]

Ashu was killed; the revolver used to kill the king was found on his body, as well as a talisman with "Kill, thou shalt be safe" written on it in Arabic. The son of a local coffee shop owner named Abdul Qadir Farhat identified the revolver as belonging to his father. On 11 August, the Prime Minister of Jordan announced that ten men would be tried in connection with the assassination. These suspects included Colonel Abdullah at-Tell, who had been Governor of Jerusalem, and several others including Musa Ahmad al-Ayubbi, a Jerusalem vegetable merchant who had fled to Egypt in the days following the assassination. General Abdul Qadir Pasha Al Jundi of the Arab Legion was to preside over the trial, which began on 18 August. Ayubbi and at-Tell, who had fled to Egypt, were tried and sentenced in absentia. Three of the suspects, including Musa Abdullah Husseini, were from the prominent Palestinian Husseini family, leading to speculation that the assassins were part of a mandate-era opposition group.[42]

The Jordanian prosecutor asserted that Colonel el-Tell, who had been living in Cairo since January 1950, had given instructions that the killer, made to act alone, be slain at once thereafter, to shield the instigators of the crime. Jerusalem sources added that Col. el-Tell had been in close contact with the former Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husayni, and his adherents in the Kingdom of Egypt and in the All-Palestine protectorate in Gaza. El-Tell and Husseini, and three co-conspirators from Jerusalem, were sentenced to death. On 6 September 1951, Musa Ali Husseini, 'Aoffer and Zakariyya Ukah, and Abd-el-Qadir Farhat were executed by hanging.[43]

Abdullah is buried at the Royal Court in Amman.[44] He was succeeded by his son Talal; however, since Talal was mentally ill, Talal's son Prince Hussein became the effective ruler as King Hussein at the age of seventeen. In 1967, el-Tell received a full pardon from King Hussein.

Succession crisisEmir Abdullah I had two sons: future King Talal and Prince Naif. Talal, being the eldest son, was considered the "natural heir to the throne". However, Talal's troubled relationship with his father led Emir Abdullah to remove him from the line of succession in a secret royal decree during World War II. Subsequently, their relationship improved after the Second World War and Talal was publicly declared heir apparent by the Emir.[45]

Tension between Emir Abdullah and then-Prince Talal continued, however, after Talal had been "compiling huge, unexplainable debts".[46] Both Emir Abdullah and Prime Minister Samir Al-Rifai were in favor of Talal's removal as heir apparent and replacement with his brother Naif. However, the British resident Alec Kirkbride warned Emir Abdullah against such a "public rebuke of the heir to the throne", a warning which Emir Abdullah reluctantly accepted and then proceeded to appoint Talal as regent when the Emir was on leave.[46]

A major reason for the British's reluctance to allow the replacement of Talal is his well-publicized anti-British stance which caused the majority of Jordanians to assume that Kirkbride would favor the vigorously pro-British prince Naif. Thus, Kirkbride is said to have reasoned that Naif's "accession would have been attributed by many Arabs to a Machiavellian plot on the part of the British government to exclude their enemy Talal", an assumption that would give the Arab nationalist sympathetic public an impression that Britain still actively interfered in the affairs of newly independent Jordan.[47] Such assumption would disturb British interests as it may lead to renewed calls to remove British forces and fully remove British influence from the country.

This assumption would be put to a test when Kirkbride sent Talal to a Beirut mental hospital, stating that Talal was suffering from severe mental illness. Many Jordanians believed that there was "nothing wrong with Talal and that the wily British fabricated the story about his madness in order to get him out of the way."[47] Because of widespread popular opinion of Talal, Prince Naif was not given British support to succeed the Emir.

The conflicts between his two sons led Emir Abdullah to seek a secret union with Hashemite Iraq, in which Abdullah's nephew Faisal II would rule Jordan after Abdullah's death. This idea received some positive reception among the British, but ultimately rejected as Baghdad's domination of Jordan was viewed as unfavorable by the British Foreign Office due to fear of "Arab republicanism".[48]

With the two other possible claimants to the throne sidelined by the British (Prince Naif and King Faisal II of Iraq), Talal was poised to rule as king of Jordan upon Emir Abdullah's assassination in 1951. However, as King Talal was receiving medical treatment abroad, Prince Naif was allowed to act as regent in his brother's place. Soon enough, Prince Naif began "openly expressing his designs on the throne for himself". Upon hearing of plans to bring King Talal back to Jordan, Prince Naif attempted to stage a coup d'état by having Colonel Habis Majali, commander of the 10th Infantry Regiment (described by Avi Shlaim as a "quasi-Praetorian Guard"[49]), surround the palace of Queen Zein (wife of Talal)[47] and "the building where the government was to meet in order to force it to crown Nayef".[50]

The coup, if it was a coup at all, failed due to lack of British support and because of the interference of Glubb Pasha to stop it. Prince Naif left with his family to Beirut, his royal court advisor Mohammed Shureiki left his post, and the 10th Infantry Regiment was disbanded.[49] Finally, King Talal assumed full duties as the successor of Abdullah when he returned to Jordan on 6 September 1951.[49]

Marriages and childrenAbdullah married three times.[citation needed]

In 1904, Abdullah married his first wife, Musbah bint Nasser (1884 – 15 March 1961), at Stinia Palace, İstinye, Istanbul, Ottoman Empire. She was a daughter of Emir Nasser Pasha and his wife, Dilber Khanum. They had three children:

Princess Haya (1907–1990). Married Abdul-Karim Ja'afar Zeid Dhaoui.King Talal (26 February 1909 – 7 July 1972).Princess Munira (1915–1987). Never married.In 1913, Abdullah married his second wife, Suzdil Khanum (d. 16 August 1968), in Istanbul, Turkey. They had two children:

Prince Nayef bin Abdullah (14 November 1914 – 12 October 1983; a colonel of the Royal Jordanian Land Force. Regent for his older half-brother, Talal, from 20 July to 3 September 1951). Married in Cairo or Amman on 7 October 1940 Princess Mihrimah Selcuk Sultan (11 November 1922 – March 2000, Amman, and buried in Istanbul on 2 April 2000), daughter of the Ottoman Turkish prince, Şehzade Mehmed Ziyaeddin (1873–1938) and his fifth wife, Neshemend Hanım (1905–1934), and paternal granddaughter of Mehmed V through his first wife.Princess Maqbula (6 February 1921 – 1 January 2001); married Hussein ibn Nasser, Prime Minister of Jordan (terms 1963–64, 1967).In 1949, Abdullah married his third wife, Nahda bint Uman, a lady from Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, in Amman. They had one child:

Princess Naifeh (1950–); married Sameer Hilal ancestor)Abd al-MuttalibAbu Talib AbdallahMuhammad(Islamic prophet)Ali(fourth caliph)FatimahHasan(fifth caliph)Hasan Al-Mu'thannaAbdullahMusa Al-KarimMuta'inIdrisQatada(Sharif of Mecca)AliHassan(Sharif of Mecca)Abu Numayy I(Sharif of Mecca)Rumaythah(Sharif of Mecca)'Ajlan(Sharif of Mecca)Hassan(Sharif of Mecca)Barakat I(Sharif of Mecca)Muhammad(Sharif of Mecca)Barakat II(Sharif of Mecca)Abu Numayy II(Sharif of Mecca)Hassan(Sharif of Mecca)Abdullah(Sharif of Mecca)HusseinAbdullahMuhsinAuon, Ra'i Al-HadalaAbdul Mu'eenMuhammad(Sharif of Mecca)AliMonarch Hussein(Sharif of Mecca King of Hejaz)Monarch Ali(King of Hejaz)Monarch Abdullah I(King of Jordan)Monarch Faisal I(King of Syria King of Iraq)Zeid(pretender to Iraq)'Abd Al-Ilah(Regent of Iraq)Monarch Talal(King of Jordan)Monarch Ghazi(King of Iraq)Ra'ad(pretender to Iraq)Monarch Hussein(King of Jordan)Monarch Faisal II(King of Iraq)ZeidMonarch Abdullah II(King of Jordan)Hussein(Crown Prince of Jordan)

Titles and honoursTitlesStyles ofKing Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein of Jordanformerly Emir of TransjordanCoat of arms of Jordan.svgReference style His MajestySpoken style Your MajestyAlternative style SirHis Royal Highness Prince Abdullah of Mecca and the Hejaz (1882–1921)His Royal Highness the Emir of Transjordan (1921–46)His Majesty the King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (1946–1949)His Majesty the King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (1949–1951)

Postage stamp, Transjordan, 1930.Meetings of British, Arab, and Bedouin officials in Amman, Jordan, April 1921 - File 01.tifHonoursNational honoursJordan:JOR Al-Hussein ibn Ali Order BAR.svg Founding Grand Master of the Order of Al-Hussein bin AliJOR Order of the Renaissance GC.SVG Grand Master of the Supreme Order of the RenaissanceOrder of Military Gallantry (Jordan).png Founding Grand Master of the Order of Military GallantryJOR Order of the Star of Jordan GC.svg Founding Grand Master of the Order of the Star of JordanJOR Order of Independence GC.svg Grand Master of the Order of IndependenceMa'an Medal 1918.gif Sovereign of the Ma'an Medal of 1918Medal of Arab Independence 1921.gif Sovereign of the Medal of Arab Independence 1921Medal of Honour (Jordan).png Founding Sovereign of the Medal of Honour of JordanLong Service Medal.gif Founding Sovereign of the Long Service MedalForeign honoursKingdom of Egypt:Order of Muhammad Ali (Egipt) - ribbon bar.gif Knight Grand Cordon with Collar of the Order of Muhammad Ali, (1948)Iran Imperial State of Iran:Order of Pahlavi Ribbon Bar - Imperial Iran.svg Grand Collar of the Order of Pahlavi, (1949)Iraq Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq:Order of the Two Rivers - Military (Iraq) - ribbon bar.png Grand Cordon of the Order of the Two Rivers, Military Class, (1922)Ord.2River-ribbon.gif Grand Cordon of the Order of the Two Rivers, Civil Class, (1925)Order of the Hashemites (Iraq) - ribbon bar.gif Grand Master of the Grand Order of the Hashemites, (1932)Order of Faisal I (Iraq) - ribbon bar.gif Grand Cordon of the Order of Faisal I, (1932)Spain Francoist Spain:ESP Gran Cruz Merito Militar (Distintivo Blanco) pasador.svg Grand Cross of the Order of Military Merit (with white distinctive), (1949)[53]Syria Syrian Republic:Order Of Ummayad (Syria) - ribbon bar.gif Grand Cordon of the Order of the Umayyads, (1950)United Kingdom:UK OBE 1917 civil BAR.svg Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE), (1920)UK Order St-Michael St-George ribbon.svg Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG-1935), King George V Silver Jubilee Medal, (1935)GeorgeVICoronationRibbon.png King George VI Coronation Medal, (1937)Gallery

Emir Abdullah of Transjordan with Sir Herbert Samuel and Emir Shakir ibn Zayid, Amman, 1921The Emir with Sir Herbert Samuel (centre) and T. E. Lawrence (left), Amman Airfield, 1921rThe Emir at the Cairo Conference with T. E. Lawrence, Air Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond and Sir Wyndham Deedes, March 1921The Emir with Sir Herbert Samuel and Mr. and Mrs. Winston Churchill at Government House reception in Jerusalem, 28 March 1921King Abdullah bin Hussein of JordanEmir Abdullah at his Amman camp with John Whiting of the American Colony (businessman, photographer, intelligence officer) and staff, 1921

A SCHOOL BOY GREETING EMIR ABDULLAH OF TRANSJORDAN DURING HIS VISIT TO JAFFA. אמיר ( מלך ) עבדלה מירדן בביקורו ביפו. בצילום נער מבית ספר ביפו מברך את .jpg

Emir Abdullah with Arab notables during visit to JaffaEmir Abdulla with Arab Legion honour guard at Haifa port before boarding ship to TurkeyHerbert Samuel and King Faisal reviewing troops at Amman

Abdullah I bin al-Husayn (Arabic: عبد الله الأول بن الحسين, romanized: Abd Allāh al-Awwal bin al-Husayn, 2 February 1882 – 20 July 1951) was the ruler of Jordan from 11 April 1921 until his assassination in 1951. He was Emir of Transjordan, a British protectorate, until 25 May 1946,[1][2] after which he was King of an independent Jordan. He was a member of the Hashemite dynasty.

Born in Mecca, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire, Abdullah was the second of four sons of Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, and his first wife, Abdiyya bint Abdullah. He was educated in Istanbul and Hejaz. From 1909 to 1914, Abdullah sat in the Ottoman legislature, as deputy for Mecca, but allied with Britain during World War I. During World War I, he played a key role in secret negotiations with the United Kingdom that led to the Great Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule that was led by his father Sharif Hussein.[5] Abdullah personally led guerrilla raids on garrisons.[6]

Abdullah became emir of Transjordan in April 1921. He upheld his alliance with the British during World War II, and became king after Transjordan gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1946.[5] In 1949, Jordan annexed the West Bank,[5] which angered Arab countries including Syria, Saudi Arabia and Egypt, which all defended the creation of a Palestinian state.[5] He was assassinated in Jerusalem while attending Friday prayers at the entrance of the Al-Aqsa mosque by a nationalist Palestinian in 1951.[7][5] He was succeeded by his eldest son Talal.Contents1 Early political career2 Founding of the Emirate of Transjordan3 Expansionist aspirations4 Assassination4.1 Succession crisis5 Marriages and children6 Ancestry7 Titles and honours7.1 Titles7.2 Honours7.2.1 National honours7.2.2 Foreign honours8 Gallery9 Notes10 Bibliography11 Further reading12 External linksEarly political careerIn their Revolt and their Awakening, Arabs never incited sedition or acted out of greed, but called for justice, liberty and national sovereignty.

Abdullah about the Great Arab Revolt[8]In 1910, Abdullah persuaded his father to stand, successfully, for Grand Sharif of Mecca, a post for which Hussein acquired British support. In the following year, he became deputy for Mecca in the parliament established by the Young Turks, acting as an intermediary between his father and the Ottoman government.[9] In 1914, Abdullah paid a clandestine visit to Cairo to meet Lord Kitchener to seek British support for his father's ambitions in Arabia.[10]

Abdullah maintained contact with the British throughout the First World War and in 1915 encouraged his father to enter into correspondence with Sir Henry McMahon, British high commissioner in Egypt, about Arab independence from Turkish rule. (see McMahon–Hussein Correspondence).[9] This correspondence in turn led to the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans.[3] During the Arab Revolt of 1916–18, Abdullah commanded the Arab Eastern Army.[10] Abdullah began his role in the Revolt by attacking the Ottoman garrison at Ta'if on 10 June 1916.[11] The garrison consisted of 3,000 men with ten 75-mm Krupp guns. Abdullah led a force of 5,000 tribesmen but they did not have the weapons or discipline for a full attack. Instead, he laid siege to town. In July, he received reinforcements from Egypt in the form of howitzer batteries manned by Egyptian personnel. He then joined the siege of Medina commanding a force of 4,000 men based to the east and north-east of the town.[12] In early 1917, Abdullah ambushed an Ottoman convoy in the desert, and captured £20,000 worth of gold coins that were intended to bribe the Bedouin into loyalty to the Sultan.[13] In August 1917, Abdullah worked closely with the French Captain Muhammand Ould Ali Raho in sabotaging the Hejaz Railway.[14] Abdullah's relations with the British Captain T. E. Lawrence were not good, and as a result, Lawrence spent most of his time in the Hejaz serving with Abdullah's brother, Faisal, who commanded the Arab Northern Army.[10]

Founding of the Emirate of Transjordan

Abdullah arrives in Amman 1920

Abdullah 1920

Abdullah I of Transjordan during the visit to Turkey with Turkish President Mustafa Kemal 1937When French forces captured Damascus (1 October 1918) at the Battle of Maysalun (24 July 1920) and expelled his brother Faisal (27 July–1 August 1920), Abdullah moved his forces from Hejaz into Transjordan with a view to liberating Damascus, where his brother had been proclaimed King in 1918.[9] Having heard of Abdullah's plans, Winston Churchill invited Abdullah to Cairo in 1921 for a famous "tea party", where he convinced Abdullah to stay put and not attack Britain's allies, the French. Churchill told Abdullah that French forces were superior to his and that the British did not want any trouble with the French. On 8 March 1920, Abdullah was proclaimed King of Iraq by the Iraqi Congress but he refused the position. After his refusal, his brother Faisal who had just been defeated in Syria, accepted the position. Abdullah headed to north to Transjordan and established an emirate there[when?][clarification needed] after being welcomed into the country by its inhabitants.[3]

Although Abdullah established a legislative council in 1928, its role remained advisory, leaving him to rule as an autocrat.[9] Prime Ministers under Abdullah formed 18 governments during the 23 years of the Emirate.

Abdullah set about the task of building Transjordan with the help of a reserve force headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Peake, who was seconded from the Palestine police in 1921.[9] The force, renamed the Arab Legion in 1923, was led by John Bagot Glubb between 1930 and 1956.[9] During World War II, Abdullah was a faithful British ally, maintaining strict order within Transjordan, and helping to suppress a pro-Axis uprising in Iraq.[9] The Arab Legion assisted in the occupation of Iraq and Syria.[3]

Abdullah negotiated with Britain to gain independence. On 25 May 1946, the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (renamed the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan on 26 April 1949) was proclaimed independent. On the same day, Abdullah was crowned king in Amman.[3]

Expansionist aspirations

King Abdullah declaring the end of the British Mandate and the independence of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 25 May 1946.Abdullah, alone among the Arab leaders of his generation, was considered a moderate by the West.[citation needed] It is possible that he might have been willing to sign a separate peace agreement with Israel, but for the Arab League's militant opposition. Because of his dream for a Greater Syria within the borders of what was then Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon, and the British Mandate for Palestine under a Hashemite dynasty with "a throne in Damascus," many Arab countries distrusted Abdullah and saw him as both "a threat to the independence of their countries and they also suspected him of being in cahoots with the enemy" and in return, Abdullah distrusted the leaders of other Arab countries.[15][16][17]

Abdullah supported the Peel Commission in 1937, which proposed that Palestine be split up into a small Jewish state (20 percent of the British Mandate for Palestine) and the remaining land be annexed into Transjordan. The Arabs within Palestine and the surrounding Arab countries objected to the Peel Commission while the Jews accepted it reluctantly.[18] Ultimately, the Peel Commission was not adopted. In 1947, when the UN supported partition of Palestine into one Jewish and one Arab state, Abdullah was the only Arab leader supporting the decision.[3]

In 1946–48, Abdullah actually supported partition in order that the Arab allocated areas of the British Mandate for Palestine could be annexed into Transjordan. Abdullah went so far as to have secret meetings with the Jewish Agency (Golda Meyerson, the future Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, was among the delegates to these meetings) that came to a mutually agreed upon partition plan independently of the United Nations in November 1947.[19] On 17 November 1947, in a secret meeting with Meir, Abdullah stated that he wished to annex all of the Arab parts as a minimum, and would prefer to annex all of Palestine.[20][21] This partition plan was supported by British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin who preferred to see Abdullah's territory increased at the expense of the Palestinians rather than risk the creation of a Palestinian state headed by the Mufti of Jerusalem Mohammad Amin al-Husayni.[9][22]

No people on earth have been less "anti-Semitic" than the Arabs. The persecution of the Jews has been confined almost entirely to the Christian nations of the West. Jews, themselves, will admit that never since the Great Dispersion did Jews develop so freely and reach such importance as in Spain when it was an Arab possession. With very minor exceptions, Jews have lived for many centuries in the Middle East, in complete peace and friendliness with their Arab neighbours.

Abdullah's essay titled "As the Arabs see the Jews" in The American Magazine, six months before the onset of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War[23]The claim has, however, been strongly disputed by Israeli historian Efraim Karsh. In an article in Middle East Quarterly, he alleged that "extensive quotations from the reports of all three Jewish participants [at the meetings] do not support Shlaim's account...the report of Ezra Danin and Eliahu Sasson on the Golda Meir meeting (the most important Israeli participant and the person who allegedly clinched the deal with Abdullah) is conspicuously missing from Shlaim's book, despite his awareness of its existence".[24] According to Karsh, the meetings in question concerned "an agreement based on the imminent U.N. Partition Resolution, [in Meir's words] "to maintain law and order until the UN could establish a government in that area"; namely, a short-lived law enforcement operation to implement the UN Partition Resolution, not obstruct it".[24]

Historian Graham Jevon discusses the Shlaim and Karsh interpretations of the critical meeting and accepts that there may not have been a "firm agreement" as posited by Shlaim while claiming it is clear that the parties openly discussed the possibility of a Hashemite-Zionist accommodation and further says it is "indisputable" that the Zionists confirmed that they were willing to accept Abdullah's intention.[25]