8 July 2005

A Penny for Your Qualia

By Rusty Rockets

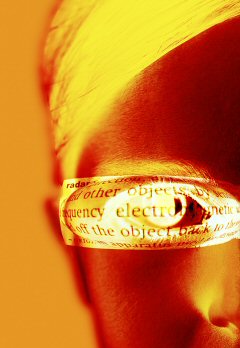

The word qualia accounts for the subjective sensation experienced by a person when they see a color or eat an ice cream. For a concept that is so simply explained it has caused much controversy and division among the science community. For example, are qualia quantifiable brain states or are they merely a matter of semantics? As an area of research, the study of qualia has predominantly been relegated to the domain of the philosophy of mind, where some of the greatest minds seem to be split on its definition or even if it exists at all. They had better make up their minds fast, because current research on subjective cognition in the field of neuroscience seems determined to drag the concept of qualia out from the shadows of philosophy of mind and into the harsh light of physical science. But even here results have been mixed, and collectively do not amount to a solid theory on subjective consciousness. Sure, they can compartmentalize certain brain functions, but they cannot provide an explanation of how these functions interact and give us self-awareness. For many scientists this last point is a non-issue, because they believe, at least theoretically, that the entire sequence of "seeing blue", formulating the word "blue" and therefore experiencing "blue" can be physically mapped in the brain and by doing so science need prove nothing else to do with consciousness.

The word qualia accounts for the subjective sensation experienced by a person when they see a color or eat an ice cream. For a concept that is so simply explained it has caused much controversy and division among the science community. For example, are qualia quantifiable brain states or are they merely a matter of semantics? As an area of research, the study of qualia has predominantly been relegated to the domain of the philosophy of mind, where some of the greatest minds seem to be split on its definition or even if it exists at all. They had better make up their minds fast, because current research on subjective cognition in the field of neuroscience seems determined to drag the concept of qualia out from the shadows of philosophy of mind and into the harsh light of physical science. But even here results have been mixed, and collectively do not amount to a solid theory on subjective consciousness. Sure, they can compartmentalize certain brain functions, but they cannot provide an explanation of how these functions interact and give us self-awareness. For many scientists this last point is a non-issue, because they believe, at least theoretically, that the entire sequence of "seeing blue", formulating the word "blue" and therefore experiencing "blue" can be physically mapped in the brain and by doing so science need prove nothing else to do with consciousness.

In his book Phantoms in the Brain (1999), Dr V.S. Ramachandran, Director of the Center for Brain and Cognition at the University of California, San Diego, states passionately that the: "need to reconcile the first-person and third-person accounts of the universe (the "I" view versus the "he" or "it" view) is the single most important unsolved problem in science." For the moment, we can at least examine some of the research and experiments that may eventually be responsible for understanding human thought, emotion and consciousness, and perhaps shed some light on the elusive questions surrounding qualia.

Simply looking at specific components of the brain is not sufficient to understanding or quantifying qualia. This "would be no more useful in understanding higher brain functions like qualia than looking at silicon chips in a microscope in an attempt to understand the logic of a computer program," says Ramachandran. He believes we need to be able to see how the parts of the brain work in unison. Biologically speaking, seamless subjective experience seems to stem from the brain synchronizing "patterns of nerve impulses," which then give rise to self-awareness.

UCLA researcher Dr Itzhak Fried and co-researcher Christof Koch, from Caltech, had a study published in Nature that presented results from an experiment that involved extracting data from consenting human subjects via intracranial electrodes. At the time Fried stated that: "Our ability to record directly from the living brains of consenting clinical patients is an invaluable tool for unravelling neural mysteries more efficiently and accurately." Fried's experiment revealed that when a person looked at an image, in this case the image of Halle Berry, a specific brain cell would be activated. Pictures of actress Halle Berry activated a neuron in the right anterior hippocampus of a different patient, as did a caricature of the actress, images of her in the lead role of the film Catwoman, and a letter sequence spelling her name.

This led the researchers to believe that specific cells were alone capable of recognition, something that was counter to current thought. But sometimes the same brain cell would respond to images of other people. This may mean that there is not necessarily a Halle Berry brain cell that develops, but rather a cell that recognizes certain characteristics of Halle Berry rather than the whole person. Perhaps the cell recognizes Berry's body shape, and all people that share a similar body shape to Berry activate that particular neuron. This would explain why the same cell would register for a number of different people, and is also consistent with the idea that neurons synchronize with other neurons to give a whole impression of a person. For example, Ramachandran discusses the condition called Capgras, where a patient thinks that that their parents or other significant people are in fact imposters. Something in the neural synchronization is missing, perhaps emotion, smell, or vocal aspects.

In a study conducted by Garrett Stanley at Harvard University, Stanley and his team used a cat's brain to record signals from a total of 177 cells in the lateral geniculate nucleus - a part of the brain's thalamus - as they played 16 second digitised (64 by 64 pixels) movies of indoor and outdoor scenes. To truly measure qualia scientifically would require an experiment such as Stanley's, where a number of people are subjected to the same controlled visual event and then have their thoughts 'recorded' and their responses and reactions compared to see how they each experienced the event. In fact, both Stanley and Itzhak's research is developing along the lines of one of the classic arguments against the concept of qualia remaining a solely individual experience. Ramachandran refers to this as the "colour-blind superscientist" argument.

In this argument, you are a superscientist with "full knowledge of the workings of the human brain", but you are completely color-blind. As a superscientist, curious about the recognition of color, you examine a patient who can see color. After extensive examination of the subject you can "completely understand the laws of color vision (or more strictly, the laws of wavelength processing), and you can tell me in advance which word I will use to describe the color of an apple, orange or lemon," explains Ramachandran. There are many thought experiments along these lines, but to many this still does not account for the concept of qualia. This is because although a scientist can thoroughly account for what color is, and show how the brain receives and processes color, it does not account for the ineffable experience of "seeing" a color.

So maybe philosophy should not be pushed to the sidelines just yet, as there still remain many questions to do with subjective experience. Think on this for a moment, if we do have the opportunity of knowing others' thoughts, emotions and experiences, would those experiences then cease, by definition, to be qualia? It is not only a matter of experiencing someone else's subjective thoughts, but also how you subjectively experience their subjective experience. For example, if two people looked at the color red, one might experience it differently because they associate red with a certain smell.

It seems that experiencing another's qualia would only have the effect of producing yet more of our own qualia: my experience of experiencing another's qualia. Conceptual quagmires such as this can perhaps only be fully unraveled by philosophers, but again we come back to the problem of semantics. Ramachandran holds that there is no barrier between subjective experience, and that there is "no vertical divide in nature between mind and matter, substance and spirit. Indeed, I believe that this barrier is only apparent and that it arises as a result of language."

Further reading:

Dr Stanley's vision page http://people.deas.harvard.edu/~gstanley/research_vision.htm