Today, obesity is considered to be undesirable, but in the past getting more fat and more energy from the diet might have been important to survival in cold places. This, according to a new study in the journalBiology Letters, might explain the dramatic differences in gut bacteria observed in people from different latitudes.

Researchers at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, and the University of Arizona say their analysis of the gut microbes of more than a thousand people from around the world showed that those living in northern latitudes had more gut bacteria that have been linked to obesity than did people living farther south.

“Our gut microbes today might be influenced by our ancestors,” said UA researcher Taichi Suzuki, noting that obesity-linked bacteria are better at extracting energy from food. “This suggests that what we call ‘healthy microbiota’ may differ in different geographic regions.”

“This observation is pretty cool, but it is not clear why we are seeing the relationship we do with latitude,” added UA co-researcher Michael Worobey. “There is something amazing and weird going on with microbiomes.”

Studies of gut microbes have become a hot research area among scientists because the proportion of different types of bacteria and Archaea in the gut seems to be correlated with diseases ranging from diabetes and obesity to cancer. In particular, the group of bacteria called Firmicutes seems to dominate in the intestines of obese people while a group called Bacteroidetes dominates in slimmer people.

Suzuki reasoned that, since animals and humans in the north tend to be larger in size – an observation called Bergmann’s rule – then perhaps their gut microbiota would contain a greater proportion of Firmicutes than Bacteriodetes. “It was almost as a lark,” Woroby recalled. “Taichi thought that if Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are linked to obesity, why not look at large scale trends in humans. When he came back with results that really showed there was something to it, it was quite a surprise.”

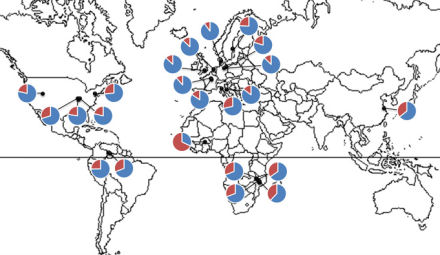

Suzuki used data published in six previous studies, totaling 1,020 people from 23 populations in Africa, Europe, North and South America and Asia. The data on gut microbiomes were essentially censuses of the types and numbers of bacteria and Archaea in people’s intestinal track.

He found that the proportion of Firmicutes increased with latitude and the proportion of Bacteriodetes decreased with latitude, regardless of sex, age, or detection methods. African Americans showed the same patterns as Europeans and North Americans, not the pattern of Africans living in tropical areas.

“Bergmann’s rule is a good one and presumed to be an adaptation for dealing with cold environments,” said UC’s Michael Nachman. “Whether gut microbes also help explain Bergmann’s rule will require experimental tests, but Taichi’s discovery adds an intriguing and completely overlooked piece of the puzzle to this otherwise well-studied evolutionary pattern.”

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Novel psychiatric drugs aimed at gut bacteria

Modified gut flora could end malnutrition

Can probiotics treat depression?

Hygiene Hypothesis linked to depression

Comments are closed.