12 July 2011

Drugs of addiction hijack our love of salt

by Kate Melville

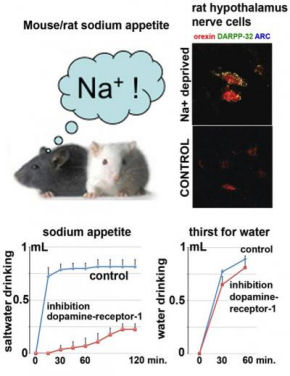

Scientists at Duke University Medical Center and the University of Melbourne have found that addictive drugs appear to hijack the same nerve cells and connections in the brain that serve a powerful, ancient instinct: our appetite for salt. In the new study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the research team demonstrate that the hunger for salt provides neural organization in the hypothalamus that subserves addiction to opiates and cocaine.

Scientists at Duke University Medical Center and the University of Melbourne have found that addictive drugs appear to hijack the same nerve cells and connections in the brain that serve a powerful, ancient instinct: our appetite for salt. In the new study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the research team demonstrate that the hunger for salt provides neural organization in the hypothalamus that subserves addiction to opiates and cocaine.

"We were surprised and gratified to see that blocking addiction-related pathways could powerfully interfere with sodium appetite," said study co-author Wolfgang Liedtke. "Our findings have profound and far-reaching medical implications, and could lead to a new understanding of addictions and the detrimental consequences when obesity-generating foods are overloaded with sodium."

Deeply embedded pathways of an ancient instinct may help explain why addiction treatment with the chief objective of abstinence is so difficult. This may be relevant given the appreciable success of maintenance approaches that don't involve abstinence, like replacing heroin with methadone and cigarettes with nicotine gum or patches. "The work opens new pathways of experimental approach to addiction," noted Derek Denton, of the University of Melbourne.

The study is the first to examine gene regulation in the hypothalamus for salt appetite. The researchers used two techniques to induce the instinctive behavior in mice - they withheld salt for a while combined with a diuretic and they also used the stress hormone ACTH to increase salt needs.

Liedtke said the researchers were surprised that they could detect that genes were "turned on" or "turned off" in salt appetite, these patterns were often substantially reversed within ten minutes of the animals' drinking salt solution, well before any significant salt could be absorbed from the gut into the bloodstream. The question of how this occurs is perplexing, and opens an entirely new field for exploration, Liedtke says.

Fast satisfaction of salt appetite makes sense from a survival perspective. Among wild animals, the ability to rapidly compensate for salt need by avidly lapping a salty solution means that depleted animals can drink to gratification and leave quickly, reducing their vulnerability to predators.

The Duke-Melbourne team found that when the animal harbors a robust sodium appetite, a certain region of the hypothalamus seems to become susceptible to the effects of dopamine, which is the brain's internal currency for reward.

That suggests that the state of the instinctive need, the sodium-depleted state, "spring-loads" the hypothalamus for the subjective experience of reward which follows when animals gratify the need - a satisfied feeling. This concept is substantiated by their finding that the local actions of dopamine on a sub-region of the hypothalamus are critical for the animals' instinctive behavior.

Related:

Salt: nature's antidepressant

Food For Thought

Study suggests the war on drugs might really be a war on sex

Source: Duke University Medical Center