10 November 2009

Biologists plot concept of "organismality"

by Kate Melville

A new paper by Rice University evolutionary biologists David Queller and Joan Strassmann argues that high levels of cooperation and low levels of conflict - from the genetic level on up - give a living thing its "organismality," whether it's an animal, a plant, a bacterium, or a colony. Organismality, they say, is a commonality of interests and minimal conflict that when combined, makes for an optimum level of adaptation.

A new paper by Rice University evolutionary biologists David Queller and Joan Strassmann argues that high levels of cooperation and low levels of conflict - from the genetic level on up - give a living thing its "organismality," whether it's an animal, a plant, a bacterium, or a colony. Organismality, they say, is a commonality of interests and minimal conflict that when combined, makes for an optimum level of adaptation.

The paper, published in Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society Biological Sciences, contends that the notion of organismality is not merely a matter of semantics, but rather posits central features governing the explicit organization of life. "The scientific community could choose any name they want for entities with extensive cooperation and very little conflict, but the existence of such entities is one of the striking features of life, and explaining how they evolve should therefore be an important task," note the researchers.

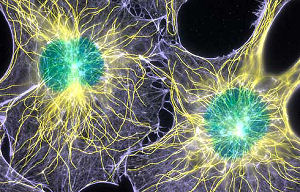

The ideas presented in the paper stem from previous research into the conflicts and cooperation that drive Dictyostelium amoebas (slime molds) and social insects. "Adaptation is what makes living things different from nonliving things, to my mind, so the concept of organism is centered on that," Queller said. "A colony of honeybees is an organism because of its sense of shared purpose. A high degree of cooperation and low level of conflict - even when the potential for conflict is there - is a primary trait of an organism, whether its components share a body or not."

Their schema for identifying organismality centers on charts that separate living things into four groups, based on observed levels of cooperation and conflict. "One thing I think is really important about the paper is the idea that the opposite of high cooperation is not conflict. It's absence of cooperation," stressed Strassmann. "That allows us to put conflict on a different axis from cooperation, and divide the social space into organisms, societies, competitors and simple groups."

Queller and Strassmann have analyzed dozens of species in three distinct classes of groups to determine where they land on the organismal charts, based on their levels of cooperation and conflict. On the cellular level, whales, mice, redwoods, the malarial parasite Plasmodium in mosquitoes and Dictyostelium rank high on the organismality scale for their levels of cooperation with little conflict.

Humans are obviously organismal, Queller and Strassmann agree. All the body parts, from the macro level (arms and legs) to the micro (cells) work nicely together with very little conflict. But unlike the honeybee colony, a city is not organismal. Though the human colony requires a great deal of cooperation to keep it running, it is, they said, "far too full of conflicts."

On the level of groups of multicellular individuals, the Portuguese man-of-war is a paragon of organismality, according to the researchers. Technically a colony of sea-going polyps, each polyp seems to know its place, taking on a specialized duty that contributes to the survival of the whole. "The cooperators have become so close as to blur their boundaries," says Strassman.

In the third grouping of two-species pairings that may seem simply symbiotic, they find close cooperation without conflict is often necessary for the survival of both parties. The relationship between mitochondria and the host cells they power is one example; bobtail squid and the bacteria that allow them to light up in return for sustenance is another.

Related:

Predator-prey relationships a key driver in nature's synchronicity

Bacteria found to exhibit anticipatory behavior

Constructal law unifies animate and inanimate designs of nature

New Rationale For Biological Complexity Proposed

Evidence Of Altruism In Plants

Source: Rice University