4 November 2005

Japan's Space Program Comes of Age

By Rusty Rockets

Largely out of the media spotlight, Japan has forged ahead in the space race and asserted its celestial competency by conducting a number of ambitious missions. The most significant of the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency's (JAXA) missions currently underway is the unmanned Hayabusa (Falcon) mission, which involves landing a spacecraft on an asteroid, collecting a sample and returning the sample to Earth for analysis.

Largely out of the media spotlight, Japan has forged ahead in the space race and asserted its celestial competency by conducting a number of ambitious missions. The most significant of the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency's (JAXA) missions currently underway is the unmanned Hayabusa (Falcon) mission, which involves landing a spacecraft on an asteroid, collecting a sample and returning the sample to Earth for analysis.

While returning asteroid chunks to Earth is the primary goal, the mission may also improve methods on how to better track and monitor asteroids, a subject close to many astronomers' hearts. Many scientists believe that NASA has not done enough in this area, pointing out the worrying 2 percent odds of asteroid MN4 hitting the Earth at some time in the future. The B612 Foundation (a group of scientists concerned about the lack of action to protect Earth from near Earth asteroids) is somewhat scathing in their appraisal of NASA's near Earth object/near Earth asteroid (NEO; NEA) priorities. "One is science, the other public safety. Both are justified and only one is being dealt with responsibly at the moment," said a B612 representative.

NASA is however, a collaborator in the Hayabusa mission and was even supposed to load their own rover onto Hayabusa, but funding issues made this impossible. NASA has also conducted asteroid missions of their own in the past: Galileo and NEAR Shoemaker. Galileo began its Jupiter bound journey in 1989, and was to be attributed with the first asteroid flyby when it passed within 1,000 miles of asteroid 951 Gaspra. NEAR Shoemaker, on the other hand, was charged with a mission not unlike that of the Hayabusa mission. NEAR Shoemaker was to closely orbit the NEA Eros, and collect data such as composition, internal mass distribution, spin state and Eros' magnetic field. NEAR Shoemaker, launched in 1996, was also the first craft to make a soft landing on an asteroid and collect composition data using its gamma-ray spectrometer.

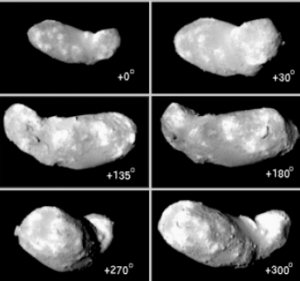

Like the NEAR Shoemaker mission, Hayabusa is intended to study the shape, spin, topography, color, composition, density, and history of a small "Earth-approaching type" asteroid called Itokawa. Scientists are interested in asteroids because they are believed to be the celestial equivalent of terrestrial fossils and by analyzing them, scientists can gain a greater understanding of the solar system in general.

Bringing back a sample of Itokawa to Earth for analysis will be the most significant aspect of the Hayabusa mission, an objective that if successful will be an international first. To accomplish this goal the Hayabusa vessel will execute a landing sequence specific to low gravity (or micro-gravity) conditions, which is not so much of a landing, but rather a 1 second bounce. As Hayabusa "lands" it will fire a projectile weighing a fraction of an ounce into Itokawa's surface at a speed of 0.2 miles/second. After the projectile breaks the surface of the asteroid, Hayabusa's sampler horn will collect the ejecta and store it in a capsule housed in the Hayabusa craft. The sample collection is due to take place this month. The operation will consist of one rehearsal and two sampling runs. To further aid data collection another feature of the Hayabusa craft is its companion robotic probe called Minerva, that the Japanese intriguingly call a "new motion mechanism." Like the Hayabusa craft itself, once released (during one of the rehearsals) the Minerva probe is designed to bounce, rather than drive, along Itokawa's surface. Minerva's job is to take pictures and measure the asteroid's temperature.

Bringing back a sample of Itokawa to Earth for analysis will be the most significant aspect of the Hayabusa mission, an objective that if successful will be an international first. To accomplish this goal the Hayabusa vessel will execute a landing sequence specific to low gravity (or micro-gravity) conditions, which is not so much of a landing, but rather a 1 second bounce. As Hayabusa "lands" it will fire a projectile weighing a fraction of an ounce into Itokawa's surface at a speed of 0.2 miles/second. After the projectile breaks the surface of the asteroid, Hayabusa's sampler horn will collect the ejecta and store it in a capsule housed in the Hayabusa craft. The sample collection is due to take place this month. The operation will consist of one rehearsal and two sampling runs. To further aid data collection another feature of the Hayabusa craft is its companion robotic probe called Minerva, that the Japanese intriguingly call a "new motion mechanism." Like the Hayabusa craft itself, once released (during one of the rehearsals) the Minerva probe is designed to bounce, rather than drive, along Itokawa's surface. Minerva's job is to take pictures and measure the asteroid's temperature.

When Hayabusa approaches Earth, the capsule containing the samples will detach from Hayabusa at a distance equal to half the distance to the Moon. It is then expected to enter Earth's atmosphere at a speed of 7.4 miles per second and reach temperatures of 5432& #176;F. JAXA say that they have developed a new material that will withstand such re-entry temperatures (fingers crossed).

One of the problems faced by scientists was how Hayabusa would cover the billions of miles needed to complete the mission, as the return journey alone will be around 1.24 billion miles. Overcoming the problem of having enough fuel to complete the mission means that JAXA can add a world first to their list of achievements, as Hayabusa is the first long-distance interplanetary probe to use an ion engine as its main propulsion device. An ion engine, explains JAXA, gets thrust from ionized gas accelerated by electricity. As a result, the engine only requires a tenth of the fuel and can accelerate for longer periods than traditional engines. But things do go wrong, and during Hayabusa's flight to Itokawa a solar flare damaged the craft's solar cells. The damage forced a three-month delay in Hayabusa's rendezvous with Itokawa.

Because of the huge distances involved, Hayabusa is steered by what JAXA calls an "autonomous navigation technique," meaning that it guides itself. This is necessary since any emergency instructions, such as evasive maneuvers, that JAXA might send, would take many seconds, or minutes, to reach the craft.

Apart from having its own smart guidance system, Hayabusa may also set a precedent for how prospecting can be carried out throughout the solar system. If successful, Hayabusa's sampling technique could be used to look for asteroids that might contain minerals, metals, organic compounds or water ices. Such resources could be used to assist future space construction and bypass the current expensive method of lobbing materials out of Earth's gravity.

One of the other goals of the mission is to attempt to answer the question of whether meteorites come from asteroids. "The samples of Itokawa collected and returned by Hayabusa could provide the first direct evidence of the link between asteroids and

meteorites," say the JAXA team. The recent photographs taken of Itokawa by Hayabusa certainly make a convincing case for this connection, because many boulders can be seen clinging to its surface. "Imagine one of these boulders flying in space. If it came to the Earth's vicinity, we would observe it as a tiny independent near-Earth asteroid," explains a JAXA representative.

One of the other goals of the mission is to attempt to answer the question of whether meteorites come from asteroids. "The samples of Itokawa collected and returned by Hayabusa could provide the first direct evidence of the link between asteroids and

meteorites," say the JAXA team. The recent photographs taken of Itokawa by Hayabusa certainly make a convincing case for this connection, because many boulders can be seen clinging to its surface. "Imagine one of these boulders flying in space. If it came to the Earth's vicinity, we would observe it as a tiny independent near-Earth asteroid," explains a JAXA representative.

While there is still a lot of work left in the Hayabusa mission, JAXA are rolling with the momentum of their current successes, and they have many more ambitious projects ahead, including a lunar exploration mission. Their philosophy is that exploring the solar system is no different to terrestrial archaeological digs, and analyzing celestial bodies such as asteroids and the moon will lead to a greater understanding of the solar system and the origins of our Earth. JAXA's relatively recent step into the ring among the traditional space agencies has been welcomed by all, as their outlook seems to be both an ambitious and holistic approach to space exploration. As the B612 Foundation enthusiastically exclaimed: "The more the merrier!"

Pics courtesy JAXA