8 September 2006

MySpace And The Dumbing Down Of Friendship

By Rusty Rockets

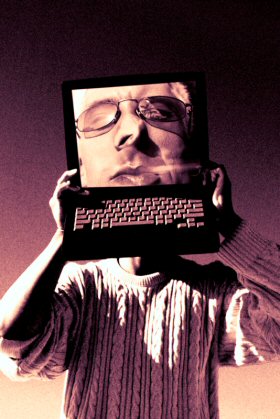

Some commentators have predicted that the Internet will one day become self-aware (whatever that means), but until the day it starts moaning about superhighway traffic jams I'd say all bets are off. The truth is we don't need to entertain such wild scenarios regarding technology when we can witness some disturbingly real ones emerging before our very eyes. At least we could, if we weren't so preoccupied with electronic gadgets and digital communications gizmos.

Some commentators have predicted that the Internet will one day become self-aware (whatever that means), but until the day it starts moaning about superhighway traffic jams I'd say all bets are off. The truth is we don't need to entertain such wild scenarios regarding technology when we can witness some disturbingly real ones emerging before our very eyes. At least we could, if we weren't so preoccupied with electronic gadgets and digital communications gizmos.

According to some worrying new studies, people who invest their time developing online relationships in social networking websites like Myspace and Facebook are becoming increasingly less aware of their real offline friends and family. And it's not just the Internet that's distracting us from our respective social milieus. Mobile phones, iPods, Palm Pilots and game consoles all suck-up precious face-to-face time in a culture that was already television obsessed to begin with.

As far as technologies go, communications is a biggy. From cave paintings and maps to the written word, the printing press, radio and television, human communication has continually, fundamentally and permanently changed the way in which we interact. But the changes are not all positive, and we increasingly find that the benefit of greater connectivity, speed and access to information has come at a cost. As digital media draws geographically remote people closer together, we find that we are proportionally being displaced from those closest to us, such as friends, family and work colleagues. Of course, even if it were possible to turn back the clock to a much simpler time, we probably wouldn't. Technology is addictive. What would we do with our time if we couldn't tap out a text message, play a video game, or logon to one of a myriad of popular networking sites?

Most of us are probably too busy interfacing with some digital device to notice this technological body-snatching, but at least one tech-savvy communications guru is fired-up enough to shake us from our digitally induced torpor and encourage us to shout: "I'm as mad as hell and I'm not going to take this anymore!"

Michael Bugeja, director of the Greenlee School of Journalism and Communication at Iowa State University, argues that our obsession with technology, especially our desire for greater connectivity, has created an "interpersonal divide." An observation that also happens to be the title Bugeja's book, Interpersonal Divide: The Search for Community in a Technological Age. In it, Bugeja argues that the plethora of electronic devices available to us as a way to supposedly enhance social relations, are actually responsible for many of society's problems. "People who use these gadgets and consume these services in their homes are spending more time apart from each other and their friends and neighbors. Then they go to work and use the same gadgets again. Then they become depressed because of work-related stress or family-related dysfunction and seek self-improvement - again using the same appliances and services that are the source of their problems, listening to inspirational videos or visiting Web sites instead of resolving issues interpersonally, face-to-face."

According to Bugeja, it is a longing for acceptance that drives our love of technological gadgetry, but what really ends up happening is that we have to change our value systems to accommodate the new technology. "We yearn for acceptance and routinely look to media and technology to bridge the interpersonal void," said Bugeja. "Electronic communication promised to enhance relationships with family and friends, to increase productivity at work, and to provide us with more leisure time at home. Instead, our personal and professional relationships often falter because communication systems alter value systems, with the primary emphasis on profit and entertainment." It's a big claim, but is he right?

Ask any member of Myspace or Facebook whether their lives have changed since using these online social networking sites and they will likely tell you - after numerous wisecracks and paranoid responses - that their lives remain unchanged. They'll contend that they still keep in touch with family and friends, despite spending many hours chatting online to people they will likely never meet face-to-face. We have 24-hour days, 16 of which are usually spent sleeping and working; so how is it possible to maintain online relationships, build and maintain intricate personal homepages, and still devote quality time to real social networks? Bugeja argues that the perception that we keep up with our offline friends and family is delusory, claiming that we: "convince ourselves that we are interacting responsibly with family and friends simply because we are keeping up with their lives. We marvel at the convenience of digital technology, remembering how time-consuming it was to pen letters, develop snapshots, or see relatives during holidays and vacations."

One's first impulse is to deny Bugeja's claim, and prove that it is possible to socialize online and devote quality time to offline relationships. But none of the alternative explanations seem all that encouraging - or healthy. Studies show that people are actually burning the candle at both ends and choosing online activities or gaming action over sleep. As a result, compulsive online behaviors represent a new and widespread class of addiction; right up there with substance abuse and problem gambling. Others believe that people can find the time for both communications gadgetry and family because they are using interactive technologies in place of television. This is a positive transition, apparently, because it means that people are no longer just vegetating in front of the box, but are actually communicating with one another.

Rather than alleviating fears, however, this latter explanation goes to the very heart of the problem. The interpersonal divide, according to Bugeja, is exacerbated because we have afforded our offline relationships the same status as our online ones. Bugeja says that both important offline and online relationships have become "homogenized" due to the identical ways in which we communicate with both realms. "We are seldom out of touch with anyone anywhere anymore," said Bugeja. "An electronic gadget or portable computer is usually within reach. Many individuals enjoy instantaneous access to family, friends and colleagues and yet, despite such contact, feel a void in their lives. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, some of us are losing the ability to interact meaningfully with others - face-to-face - because we opt for on-demand rather than physical contact, relying on technology to mediate our thoughts, words, and deeds. And we pay a price, not only in access fees, but in feelings." Phew.

But hang on. Used the right way, communication technologies can be invaluable. While Bugeja has published a good old-fashioned book on the perils that media systems pose to society, he would surely not begrudge the extra exposure that the Internet provides his publication. And let's not forget that today's youth, for better or worse, are growing up with online networking sites as a part of their everyday lives. According to Purdue University, over 9 million college students have Facebook accounts (encompassing 2,000 universities and 25,000 high schools), which they can use to contact and catch up with old friends, other students, access course information, organize social events or address important campus issues. In a recent study on education and the Internet, one Michigan State researcher even associated improvements in grade point averages (GPAs) among geographically remote students with Internet access. "Improvements in reading achievement may be attributable to the fact that spending more time online typically means spending more time reading; GPAs may improve because GPAs are heavily dependent on reading skills."

The benefits to society are obvious, but the convenience and speed of these devices is a trap that Bugeja believes has distanced us from those closest to us. Bugeja would have us believe that there is an authenticity in real world relationships, where Baby Boomers have "yellowed letters with black-and-white photographs of grandparents and ancestors - precious as time itself," and; "The children of Baby Boomers will have email and pixels, for they have been taught to elevate convenience, which technology can provide, over substance, which it cannot." Is it possible to balance the costs and benefits of new communications technologies; or are we just evolving into a highly connected yet emotionally handicapped species?