11 November 2005

Face Transplants - Here's Looking At You

By Rusty Rockets

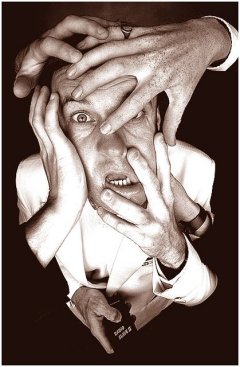

"It is the common wonder of all men, how among so many millions of faces, there should be none alike," said Thomas Browne in his Religio Medici, while Lauren Becall drawled: "your whole life shows in your face and you should be proud of that." The face continues to be the ultimate mark of a person's identity and films such as Face Off have premised the idea that a person's identity is inextricably linked to their face. For the sake of expediency, pop-culture depictions of face transplants are made to look simple, and the ethical questions that arise are so gossamer thin that they are barely noticeable. But it seems reality is about to hit home as a group of surgeons ready themselves to make history, and in doing so will test the boundaries of medicine and bioethics. Of course, there is also the small matter of finding a willing participant to join them on their pioneering quest to perform face transplantation surgery.

"It is the common wonder of all men, how among so many millions of faces, there should be none alike," said Thomas Browne in his Religio Medici, while Lauren Becall drawled: "your whole life shows in your face and you should be proud of that." The face continues to be the ultimate mark of a person's identity and films such as Face Off have premised the idea that a person's identity is inextricably linked to their face. For the sake of expediency, pop-culture depictions of face transplants are made to look simple, and the ethical questions that arise are so gossamer thin that they are barely noticeable. But it seems reality is about to hit home as a group of surgeons ready themselves to make history, and in doing so will test the boundaries of medicine and bioethics. Of course, there is also the small matter of finding a willing participant to join them on their pioneering quest to perform face transplantation surgery.

The obstacles for facial transplant surgery are just as much about ethics, psychological and societal issues as they are about the technical feasibility of such a procedure. Despite our growing obsession with - and normalization of - cosmetic surgery, it is forgivable if people respond to the idea of transplanting a deceased person's face onto another with visceral unease. Facial transplantation is obviously not a lighthearted matter, but then neither are the circumstances under which prospective recipients have come to be in their particular situation. Potential facial transplant patients are those beyond conventional reconstruction surgery. The significant removal of facial tissue due to car accidents, fires and disease affects only a small fraction of people but the public cannot get a full understanding of how prevalent these types of afflictions are, as people with such disfigurements tend to keep themselves away from public scrutiny. In this respect, it could be argued they have suffered societal death.

The new lease on life that a facial transplant could offer an individual is immense, and not limited solely to the prospect of overcoming social isolation. Experts attempting to organize the first facial transplant, or "composite tissue allotransplantation", at the University of Louisiana (UL) say that a facial transplant may provide the recipient with the chance to regain facial muscle function. Things that we take for granted such as chewing, breathing and closing our eyes to sleep, may once again be possible. One person who is fully aware of the difficulties faced by severely scarred burn patients is "spray-on-skin" pioneer Dr. Fiona Wood, of the Royal Perth Hospital in Western Australia. Dr. Wood became a prominent figure when she used her spray-on-skin to treat the victims of the 2002 terrorist bombings in Bali. "Burns can be truly gruesome injuries. Without skin, the body weeps copious fluids and is dangerously vulnerable to infection. If a patient survives, they face living with disfiguring scars that tighten and restrict movement," said Dr Stanley, in July 2005's edition of Nature.

The UL team, headed by director of plastic surgery research, John Barker, is of the opinion that the skills and experience needed to transplant a human face are now available. Aided by a cocktail of anti-rejection drugs, a UL research team performed two of the world's first successful hand transplants four years ago at Jewish Hospital in Louisville. The UL team maintain that the questions that remain to be answered consist purely of a "wide array of ethical and psychosocial issues." Osborne Wiggins, UL's medical ethicist, adds that: "The hopes, anxieties and emotional stability of organ transplant recipients have always posed ethical concerns. These issues become even more critical in face transplant recipients. At stake is a person's self-image, social acceptability and sense of normalcy."

While the ethical issues are still to be resolved, questions also remain as to whether the technical details have been adequately addressed. The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSE) are wary of facial transplants, and do not seem to share the UL team's confidence that the technical know-how is available, adding that the "procedure appears physically to be very hazardous." It is certain that the recipient would be subject to a life-long course of immunosuppressive drugs to prevent tissue rejection, but this in itself is probably worth what the recipient would gain in life quality. The bigger concern that the RCSE highlights, and a factor not alien to Dr. Barker, is that the skin is the most susceptible organ to rejection, and, says the RCSE: "Acute rejection of the skin has been reported in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy after upper limb, and also after abdominal wall transplantation."

While the ethical issues are still to be resolved, questions also remain as to whether the technical details have been adequately addressed. The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSE) are wary of facial transplants, and do not seem to share the UL team's confidence that the technical know-how is available, adding that the "procedure appears physically to be very hazardous." It is certain that the recipient would be subject to a life-long course of immunosuppressive drugs to prevent tissue rejection, but this in itself is probably worth what the recipient would gain in life quality. The bigger concern that the RCSE highlights, and a factor not alien to Dr. Barker, is that the skin is the most susceptible organ to rejection, and, says the RCSE: "Acute rejection of the skin has been reported in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy after upper limb, and also after abdominal wall transplantation."

It must be understood that facial transplants of the type being discussed here are radically different from current procedures using autologous tissue (the recipients own tissue). The face would involve a large amount of tissue - taken from a cadaver - that would require arterial inputs and venous drainage. The RCSE say that: "In the event of either a technical failure or acute rejection, the transplant would have to be removed. As previous skin grafts would have been removed prior to the transplantation, the patient would have to have further skin grafts of their own tissue to replace the failed rejected tissue, assuming that there were sufficient healthy donor skin sites. In this event there is the possibility that there would be even more scarring than there was originally."

The RCSE add that it is not possible to predict the likelihood of immunological rejection after facial transplantation, "but a graft loss of around 10 percent from acute rejection within the first year and significant loss of graft function from chronic rejection in around 30-50 percent of patients over the first 2-5 years might be a reasonable estimate." This is a significant statistic as there isn't much in the way of a plan B should a facial transplant fail. So, even a recipient who seems to have very little to lose and everything to gain may in fact still be risking too much.

Another intriguing aspect of facial transplant surgery falls yet again into the realm of ethical concerns: Assuming surgery is successful, what will the appearance of the face look like? Will it look like the deceased donor, or more like the recipient? Apart from raising many psychological questions in regard to a sense of self and identity in the recipient, the family of the deceased also needs to be considered. Will family members of the deceased be able to recognize their departed loved one? Dr. Barker is fully aware of such concerns and has deliberated with colleagues and psychologists to provide answers to such questions by transplanting faces onto cadavers. The end result is said to be a mix between the two, with neither identity being fully recognizable. The RCSE agree, saying that the tissue would mold to the recipients bone structure, while exhibiting the characteristics of the donor's soft tissue.

Would a world where face transplantations are possible create a wave of unrealistic expectations among the general public? Would people who were not happy with their looks seek facial transplant surgery? The most obvious scenario in our youth obsessed culture is the request for a younger looking face, a possibility not overlooked by the RCSE in their own assessments. From this scenario even more speculative questions arise purely out of curiosity. Just what happens when younger skin is attached to an older body, would the facial tissue age faster?

Doctors and scientists may never have to actually address these questions. The many technical and ethical milestones that need to be addressed mean there is always the chance that other technologies may make facial transplantation redundant. Dr. Wood's "spray-on-skin" is just one early indication of possible technologies that may be available in the future.

Facial transplants are sure to invoke mixed feelings and anxieties among potential recipients. A lifetime of immunosuppressive drugs may be bearable, but losing their entire face yet again may just be too much to contemplate. Given this and the RCSE's long list of concerns, proceeding with a facial transplant may seem almost irresponsible to anyone not in the position of a potential recipient, but then this is the real crux of the matter. Ultimately, only the individuals contemplating such groundbreaking and potentially life changing surgery are able to make such a difficult decision.