8 July 2014

Scientists uncover biggest-ever flying bird

by Will Parker

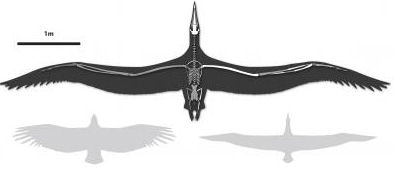

The fossilized remains of an extinct giant bird with a wingspan of 24 feet place the creature above theoretical upper limits for powered flight in animals, leaving scientists to wonder how the enormous bird managed to take to the air. Named Pelagornis sandersi, the new species was more than twice as big as the Royal Albatross, the largest flying bird alive today.

The fossilized remains of an extinct giant bird with a wingspan of 24 feet place the creature above theoretical upper limits for powered flight in animals, leaving scientists to wonder how the enormous bird managed to take to the air. Named Pelagornis sandersi, the new species was more than twice as big as the Royal Albatross, the largest flying bird alive today.

Daniel Ksepka (pictured), the author of a study describing the bird in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, said the fossilized remains were very well-preserved, a rarity because of the paper-thin nature of the bones in birds. The strikingly well-preserved specimen consisted of multiple wing and leg bones and a complete skull.

The fossil was discovered when excavations began for a new terminal at the Charleston International Airport in South Carolina. The presence of bony tooth-like spikes in the jaw allowed Ksepka to identify the find as a previously unknown species of the Pelagornithidae, an extinct group of giant seabirds.

Ksepka, from the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, estimated the length of the feathers based on the relationship between bone lengths and feather lengths in living birds. Despite its huge size, Ksepka has no doubt that P. sandersi flew. Its paper-thin hollow bones, stumpy legs and giant wings would have made it at home in the air but awkward on land. But because it exceeded what some mathematical models say is the maximum body size possible for flying birds, what was less clear was how it managed to take off and stay aloft despite its massive size.

To find out, Ksepka fed the fossil data into a computer program designed to predict flight performance given various estimates of mass, wingspan and wing shape. The analyses showed P. sandersi was probably too big to take off simply by flapping its wings and launching itself into the air from a standstill. The study speculates that P. sandersi may have gotten off the ground by running downhill into a headwind or taking advantage of air gusts to get aloft, much like a hang glider.

Once it was airborne, Ksepka's simulations suggest that the bird's long, slender wings made it an incredibly efficient glider. By riding on air currents that rise up from the ocean's surface, P. sandersi was able to soar for miles over the open ocean without flapping its wings, occasionally swooping down to the water to feed on soft-bodied prey like squid and eels.

"These giant birds occurred all over the globe for tens of millions of years, but vanished during the Pliocene, just three million years ago," said Ksepka, who hopes the find will shed light on why the family of birds that P. sandersi belonged to eventually died out.

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Climate change, not humans, wiped out megafauna, claim Aussie scientists

Mass extinction event linked to invasive species

Fossil analysis indicates dinosaurs used feathers for courtship

Source: National Evolutionary Synthesis Center