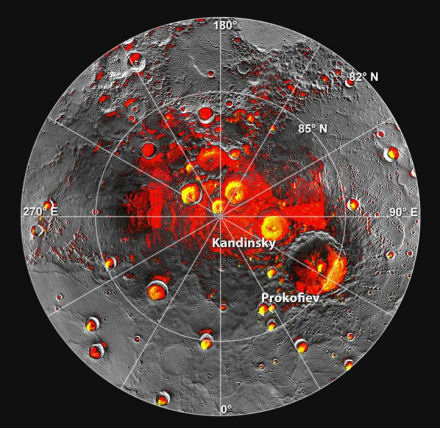

Given its proximity to the Sun, the existence of frozen water is counter-intuitive, but the tilt of Mercury’s rotational axis is almost zero, meaning there are areas at the planet’s poles that never see sunlight

The new evidence is provided by three independent papers published in Science Express. The papers looked at;

- Measurements of excess hydrogen at Mercury’s north pole obtained withMessenger’s Neutron Spectrometer,

- Measurements of the reflectance of Mercury’s polar deposits at near-infrared wavelengths, and

- The first detailed models of the surface and near-surface temperatures of Mercury’s north polar regions that utilize the actual topography of Mercury’s surface.

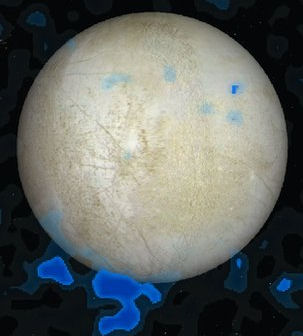

The new data strongly indicate that water ice is the major constituent of Mercury’s north polar deposits. While that ice is exposed at the surface in the coldest of those deposits, the scientists say the ice appears to be buried beneath an unusually dark material across most of the deposits (areas where temperatures are a bit too warm for ice to be stable at the surface itself).

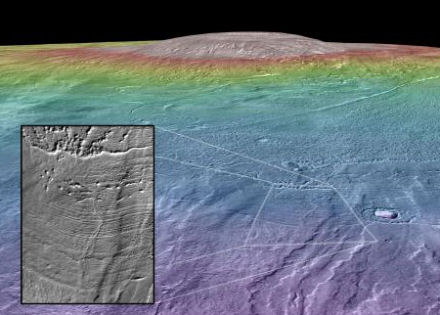

Data from Messenger’s Mercury Laser Altimeter (MLA) corroborate the radar results, says Gregory Neumann of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. In a second paper, Neumann and his colleagues report that the first MLA measurements of the shadowed north polar regions reveal irregular dark and bright deposits at near-infrared wavelength near Mercury’s north pole.

“These reflectance anomalies are concentrated on poleward-facing slopes and are spatially collocated with areas of high radar backscatter postulated to be the result of near-surface water ice,” Neumann explains. “Correlation of observed reflectance with modeled temperatures indicates that the optically bright regions are consistent with surface water ice.”

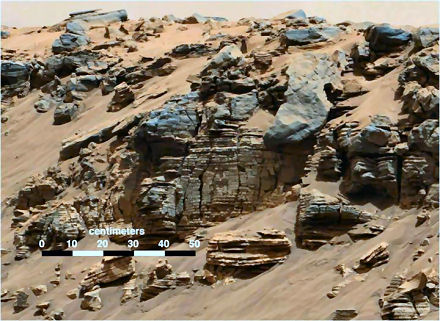

The MLA also recorded dark patches with diminished reflectance, consistent with the theory that the ice in those areas is covered by a thermally insulating layer. Neumann suggests that impacts of comets or volatile-rich asteroids could have provided both the dark and bright deposits, a finding corroborated in a third paper led by David Paige of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Paige and his colleagues provided the first detailed models of the surface and near-surface temperatures of Mercury’s north polar regions that utilize the actual topography of Mercury’s surface measured by the MLA. The measurements “show that the spatial distribution of regions of high radar backscatter is well matched by the predicted distribution of thermally stable water ice,” he reports.

According to Paige, the dark material is likely a mix of complex organic compounds delivered to Mercury by the impacts of comets and volatile-rich asteroids, the same objects that likely delivered water to Mercury. The organic material may have been darkened further by exposure to the harsh radiation at Mercury’s surface, even in permanently shadowed areas.

While the new findings provide compelling evidence for water on Mercury, the dark insulating material raises new questions. “Do the dark materials in the polar deposits consist mostly of organic compounds?” ponders Sean Solomon, principal investigator of the Messenger mission. “What kind of chemical reactions has that material experienced? Are there any regions on or within Mercury that might have both liquid water and organic compounds? Only with the continued exploration of Mercury can we hope to make progress on these new questions.”

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Asteroid bombardment pushed life into fast lane

Stars manufacturing complex organic matter?

Discovery of asteroid water hints at oceans’ origins

Strong evidence for liquid water in comet

![14mm Male Glass Bowl For Water Pipe Hookah Bong Replacement Head [HIGH QUALITY] picture](/store/img/g/q1EAAOSw9hBmBNK-/s-l225/14mm-Male-Glass-Bowl-For-Water-Pipe-Hookah-Bong-Re.jpg)

Comments are closed.