Despite our preoccupation with all things gastronomic, surprising little is known about how food preparation affects the energy it supplies to our bodies. Now, for the first time, Harvard researchers have shown that cooked food yields more energy than raw, leading them to speculate that cooking played a key role in driving the evolution of modern humans.

“It is astonishing that we don’t understand the fundamental properties of the food we eat,” observed researcher Rachel Carmody. “All the effort we put into cooking food and presenting it – mashing it up, or cutting it, or slicing or pounding it – we don’t understand what effect that has on the energy we extract from food, and energy is the primary reason we eat in the first place.”

Carmody’s study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that cooked meat provides more energy than raw meat, suggesting that humans are biologically adapted to take advantage of the benefits of cooking, and that cooking played a key role in driving the evolution of man.

Although earlier studies have examined specific aspects of what happens during the cooking process, this is the first study to assess whether cooking affected the in vivoenergy value of food. “There had been no research that looked at the net effects – we had pieces that we could not integrate together, so we didn’t know what the overall answer was,” Carmody said.

Her experiment involved feeding two groups of mice a series of diets that consisted of either meat or sweet potatoes prepared in four ways – raw and whole, raw and pounded, cooked and whole, and cooked and pounded. Over the course of each diet, the researchers tracked changes in each mouse’s body mass, as well as how much they used an exercise wheel. The results, Carmody says, clearly show that cooked meat delivers more energy.

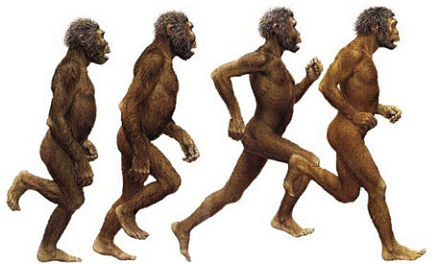

Although early humans were eating meat several million years ago, without the ability to control fire, any meat in their diet was raw, and probably pounded using primitive stone tools. Approximately 1.9 million years ago, however, a sudden change occurred. The bodies of early humans grew larger. Their brains increased in size and complexity and adaptations for long-distance running appeared.

Previously, this increase in brain size had been linked to a seafood diet rich in iodine. Carmody’s research points to another possible hypothesis – that cooking provided early humans with more energy, allowing for such energetically-costly evolutionary changes.

Interestingly, the impacts of the new findings aren’t limited to the early days of human evolution. They also lay bare the shortcomings in the Atwater system, the calorie-measurement tool used to produce modern food labels. “That system is based on principles that don’t reflect the in vivo energy availability,” Carmody explained. “Although it measures what has been digested, the human gastrointestinal system includes a whole host of bacteria, and those bacteria metabolize some of our food for their own benefit. Atwater doesn’t discriminate between food that is digested by the human or the bacteria, and increasing evidence suggests that the bacteria take a pretty good portion of the food we eat. In fact, research has shown that one of the ways to increase the value humans get, relative to the bacteria, is by processing food, and cooking is one way to do that.”

Related:

Discuss this article in our forum

Processed food cripples young brain

Food, Notorious Food

Evergreen agriculture emerges as Africa’s key to food security

BPA levels in US foods assessed for first time

![Norman Rockwell Collector Plate The Cooking Lesson 1982 KNOWLES [Free Shipping] picture](/store/img/g/mcQAAOSwgxRmKVBF/s-l225/Norman-Rockwell-Collector-Plate-The-Cooking-Lesson.jpg)

Comments are closed.