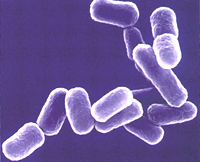

Researchers from Harvard University and Boston University have observed that in certain populations of bacteria, antibiotic resistant strains will release chemicals to assist weaker bacteria to survive, a finding that provides deep insights into bacterial complexity and antibiotic resistance.

Reporting their findings in Nature, the researchers explain that the populations most adept at withstanding doses of antibiotics are those in which a few highly resistant isolates sacrifice their own well being to improve the group’s overall chance of survival. This bacterial altruism results when the most resistant isolates produce a small molecule called indole.

Indole acts as something of a steroid, helping the strain’s more vulnerable members “bulk up” enough to fight off the antibiotic onslaught. But while indole may save the group, its production takes a toll on the fitness level of the individual isolates that produce it.

“We weren’t expecting to find this,” said lead investigator Boston University’s James J. Collins. “Typically, you would expect only the resistant strains to survive, with the susceptible ones dying off in the face of antibiotic stress. We were quite surprised to find the weak strains not only surviving, but thriving.”

The fact that the full complexity of bacteria strains can now be more accurately understood has significant ramifications for the medical community. “Now, when we measure the resistance in a population, we’ll know that it may be tricking us,” said Collins. “We’ll know that even an isolate that shows no resistance can put up a stronger battle against antibiotics thanks to its buddies.”

Related:

Microbe Colonies Show Sophisticated Learning Behaviors

Bacteria found to exhibit anticipatory behavior

Evidence Of Altruism In Plants

Forced Mutations Demonstrate Evolution In Action

Comments are closed.