First suggested by 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant, University College scientists now have empirical evidence for the theory that a pre-wired spatial framework exists in mammalian brains. The new findings may help researchers in fields as diverse as neurology, robotics and artificial intelligence.

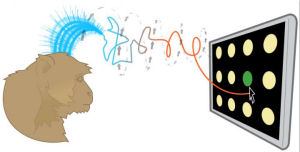

Published in the journal Science, the new study reveals that the brain’s representations of place and direction appear extremely early in an animal’s development, seemingly independently of any experience of the world.

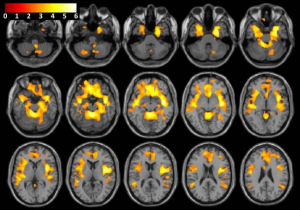

In the study, the researchers monitored the activation, or “firing,” of three different types of spatial neurons in the brains of rats, specifically in the hippocampus. As the hippocampus in humans plays a crucial role in long-term memory for events and spatial navigation, understanding its development tells us to what extent our ability to remember (and find our way) depends on innate factors and learning.

“The question of how we acquire knowledge of the outside world and form our sense of place in it is one that has challenged both scientists and philosophers for centuries,” said researcher Francesca Cacucci.

“Given that we have found that some aspects of the spatial representation come into play so early, within two weeks of birth, we think that space could be a sense that is developed independently of any experience; rather than growing out of experience of the world, it could provide a conceptual framework for experience in the first place,” concluded co-researcher John O’Keefe.

Related:

Complex Behaviors Hard-Wired Into Primate Brains

Ability to navigate may be linked to genes

Bad driving may be genetic

Comments are closed.