New evidence concerning hygiene habits has come to light at Qumran, linking an ancient Jewish sect known as the Essenes to the Dead Sea Scrolls. One of the most mysterious religious elements in Judaea around the supposed time of Jesus, the Essenes’ relationship to the scrolls has been a matter of some controversy. Now, new scientific findings from the Qumran settlement connect it to details in the scrolls, and give direct evidence of Essene culture at the site.

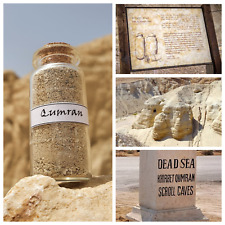

In an article in Revue de Qumran, an international bioarchaeological research team reports the results of an investigation of a suspected remote latrine site near Qumran. The site was located by following ancient clues that specify the remote placement of latrines and contains hints about unusual toiletry and hygiene practices.

Analysis of the site did indeed confirm the area as an ancient latrine site through the presence of desiccated eggs from three distinct human-specific intestinal parasite species. The control samples from the surrounding desert areas contained no parasites, human or animal.

“Frankly, I was surprised,” said paleopathologist Joe Zias. “A parasitologist I talked to told me that my chances of finding something were just about nil. Finding evidence of parasites would be easy in a latrine, but in the middle of the desert… The evidence shows conclusively that the area was a toilet. The samples contained eggs from intestinal worms that are specific to humans, [indicating] heavy and continual use of the specific site.”

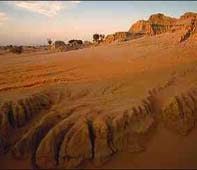

Zias noted that the heavy daily digging by the Essenes left its mark on the desert in a way that is still noticeable more than 2000 years later. “I went there and the entire area looked like somebody had plowed it, the earth was so nice and soft, while the rest of the desert was very hard,” he said. “In fact, I broke my pick collecting control samples from the other areas.”

The researchers note that the settlement’s unusual latrine practices may provide clues in solving some of Qumran’s other archaeological puzzles – in particular, questions raised by the 1,100 graves found at the site, which are almost exclusively male. “The graveyard at Qumran is the unhealthiest group that I have ever studied in over 30 years and this is readily apparent,” said Zias. “Two-thousand years ago in Jericho, 14 kilometers to the north, the chances of an adult male dying after 40 were 49 percent. But when you go to Qumran, the figure for people surviving to 40 falls to six percent – the chances of making to 40 differ by a factor of eight!”

Zias believes the lack of longevity puzzle could be explained by the community’s latrine practices and its use of still-water pools for ritual cleansing and bathing. “Burying your feces in the outdoors makes a lot of sense until you live in Qumran,” Zias explained. “By burying their fecal matter, they actually preserved the microorganisms and parasites. In the sunlight, the bacteria and parasites get zapped within a fairly short amount of time, but buried, the parasites can live in the soil for up to a year. Then people pick up things by walking through fecally contaminated soil – it’s like a toxic waste dump, and if you have any cuts on your feet…”

Additionally, the community’s bathing practices complicated the problem of daily exposure to contaminated soil. A cleansing pool was located at the settlement entrance on the return route from the latrine area and is likely to have been a fertile breeding ground for pathogens picked up from the human waste-enriched soil. “Here is where things really get bad,” Zias explained. “After they went to the latrines they were required to enter one of the emersion cisterns before they came back into the settlement. Hygienically, that sounds like a good idea – if you have fresh running water – but there is no running water at Qumran, only runoff which was collected during the three months of winter rains. They enter the cisterns where everyone else has been, with all the bacteria they’ve brought in with them, floating around. The bacterium, which usually doesn’t last long in the air and sunlight, stays active for a longer period in the sediments and is continually re-suspended in the water by people disturbing the pool. The water there may looked clean, but hygienically, it was rarely changed and must have been very dirty with the potentially fatal pathogens shared by everyone who was entering it for ritual purification.”

Ironically, both the rigorous latrine and purification practices, combined with the lack of running water appear to be the most likely causes for the extreme differences in early mortality between Qumran and Jericho. “It is not hard to imagine how sick everyone must have been,” Zias said. “As a group the men of Qumran were very unhealthy, but I think this would have been likely to have actually fed the Essenes’ religious enthusiasm,” Tabor added. “They would have seen their infirmities as punishment from God for their lack of purity and then have tried even harder to purify themselves further.”

Source: University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Comments are closed.