16 May 2006

New 3-D Map Of Cosmos Is Biggest Ever

by Kate Melville

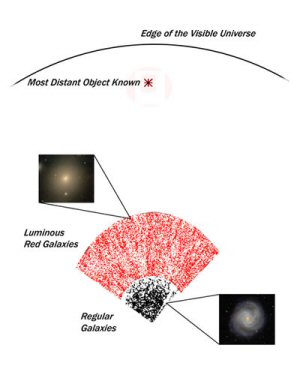

A team of astronomers have just published the largest three-dimensional map of the universe ever constructed, a wedge-shaped slice of the cosmos that spans a tenth of the northern sky. Team leaders Nikhil Padmanabhan and David Schlegel say the new map encompasses 600,000 uniquely luminous red galaxies, and extends 5.6 billion light-years deep into space, equivalent to 40 percent of the way back in time to the Big Bang.

Schlegel and Padmanabhan have previously produced smaller 3-D maps by collecting the spectra of individual galaxies and calculating their distances by measuring their redshifts. "What's new about this map is that it's the largest ever," says Padmanabhan, "and it doesn't depend on individual spectra."

The new map was made possible thanks to the Sloan Digital Sky Survey's wide-field telescope, which covers a three-degree field of view (the full moon is about half a degree), plus the choice of a particular kind of galactic "lighthouse," or distance marker: luminous red galaxies. "These are dead, red galaxies, some of the oldest in the universe - in which all the fast-burning stars have long ago burned out and only old red stars are left," said Schlegel. "Not only are these the reddest galaxies, they're also the brightest, visible at great distances."

Astronomers believe that large-scale 3-D maps like this new one will help them understand how matter is distributed in the universe. "Because this map covers much larger distances than previous maps, it allows us to measure structures as big as a billion light-years across," added Schlegel.

To create their new map, the astronomers relied on a natural astronomical ruler. The variations in galactic distribution that constitute visible large-scale structures are directly descended from variations in the temperature of the cosmic microwave background, reflecting oscillations in the dense early universe that have been measured to great accuracy by balloon-borne experiments and the WMAP satellite. The result is a natural ruler formed by the regular variations, or baryon oscillations, which repeat at intervals of some 450 million light-years. "Unfortunately it's an inconveniently sized ruler," said Schlegel. "We had to sample a huge volume of the universe just to fit the ruler inside."

The distribution of galaxies provides a measure for the mysterious dark energy that accounts for some three-fourths of the universe's density. "Dark energy is just the term we use for our observation that the expansion of the universe is accelerating," Padmanabhan explained. "By looking at where density variations were at the time of the cosmic microwave background [only about 300,000 years after the Big Bang] and seeing how they evolve into a map that covers the last 5.6 billion years, we can see if our estimates of dark energy are correct." The new map shows that the large-scale structures are indeed distributed the way current ideas about the accelerating expansion of the universe would suggest. The map's assumed distribution of dark matter, which although invisible, is affected by gravity just like ordinary matter, also conforms to current understanding.

Source: Berkeley Lab