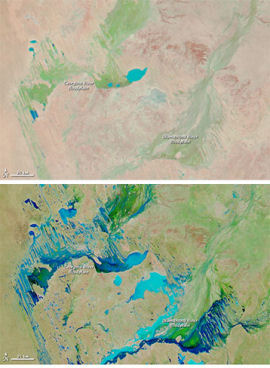

Massive extinctions of animals 45,000 to 55,000 years ago and the arrival of the first humans in ancient Australia may be linked, according to scientists at the Carnegie Institution, the University of Colorado and the Australian National University. Researchers analyzed ancient eggshells and wombat teeth to determine the diet and the environment of animals over the last 140,000 years in an effort to reconstruct what happened. Their analysis shows that there was a rapid change of diet at the time of the extinctions, which cannot be attributed to global climate change. In fact, the scientists believe that massive fires set by the first humans may have changed the delicate ecosystem of shrubs, trees, and grasses into the fire-adapted desert-scrub seen in Australia today.

The scientists work, published in Science, plotted the dietary changes of two species of large, flightless birds – the now-extinct Genyornis and the surviving emu (Dromaius) – in three Australian locations. They then corroborated their findings by analyzing ancient wombat teeth. “What your mother told you is true: You are what you eat,” said Fogel. “Eggshells and teeth both contain evidence of these animals’ diets in different forms of carbon. All three animals were plant eaters. Different types of plants metabolize different forms of carbon in distinctive ways from the CO2 they take up during photosynthesis. The tell-tale carbon varieties were preserved in the eggshells and teeth and told us what types of plants the animals ate. We saw a sudden shift in plant type coincident with the arrival of humans. The shifting diet shed light on the extinctions. The animals that relied mostly on the more palatable plant forms died out, such as Genyornis, while the animals that adapted to the less nutritious plants survived, including the emu.”

Three isotopes, or varieties, of carbon found in nature were central to the team’s study – 12C, 13C and 14C. They differ in the number of neutrons in the nucleus. By far the most abundant variety is in the lightest, 12C. About 1 percent is 13C, a heavier sibling with an additional neutron. There is even less 14C, the unstable, radioactive heavyweight of them all.

“13C is the key,” Fogel explained. “There are two main ways plants metabolize 13C. About 85 percent of plants belong to what is known as the C3 photosynthesis group. This group incorporates less 13C than plants belonging to the second most common class, C4. Thus, the differences in 13C that we detected in the eggshells and teeth pointed to the type of plants that were consumed. Although, both types of plants were present before the extinctions, we saw a quick shift in dominance from C4 drought-resistant trees, shrubs and grasses, to C3 desert plants. ”

Comments are closed.