Trips to distant parts of the solar system could become commonplace with magnetized-beam plasma propulsion, or mag-beam, said Robert Winglee, a University of Washington professor who is leading the research. “We’re trying to get to Mars and back in 90 days,” Winglee said. “Our philosophy is that, if it’s going to take two-and-a-half years, the chances of a successful mission are pretty low.”

Under the mag-beam concept, a space-based station would generate a stream of magnetized ions that would interact with a magnetic sail on a spacecraft and propel it through the solar system at high speeds that increase with the size of the plasma beam. Winglee estimates that a control nozzle 32 meters wide would generate a plasma beam capable of propelling a spacecraft at 11.7 kilometers per second (26,000 miles an hour) or more than 625,000 miles a day.

Winglee envisions units being placed around the solar system by missions already planned by NASA. One could be used as an integral part of a research mission to Jupiter, for instance, and then left in orbit there when the mission is completed. Units placed farther out in the solar system would use nuclear power to create the ionized plasma; those closer to the sun would be able to use electricity generated by solar panels.

The mag-beam concept grew out of an earlier effort Winglee led to develop a system called mini-magnetospheric plasma propulsion. In that system, a plasma bubble would be created around a spacecraft and sail on the solar wind. The mag-beam concept removes reliance on the solar wind, replacing it with a plasma beam that can be controlled for strength and direction.

Winglee acknowledges that it would take an initial investment of billions of dollars to place stations around the solar system. But once they are in place, their power sources should allow them to generate plasma indefinitely. The system ultimately would reduce spacecraft costs, since individual craft would no longer have to carry their own propulsion systems. They would get up to speed quickly with a strong push from a plasma station, then coast at high speed until they reach their destination, where they would be slowed by another plasma station. “This would facilitate a permanent human presence in space,” Winglee said. “That’s what we are trying to get to.”

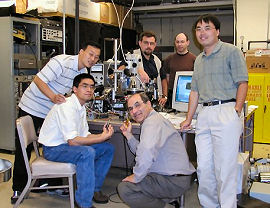

Pic courtesy University of Washington

Comments are closed.